- Introduction

- What If Truth Is a Person?

- The Ancient Roots of Person Truth

- Faith in ideas, or faithfulness to a Person?

- Knowing God vs. believing ideas about Him

- Person-truth does not give us control

- Knowing Person-truth through covenant

- Our on-and-off relationship with Person-truth

- The arch-nemesis of Person-truth

- What it means to be an authority on truth

- What is sin, if truth is a Person?

- Rethinking the Atonement of Christ

- Person-truth in an age of science and reason

- Conclusion

- Appendix A: Further Readings

- Appendix B: More on Greek and Hebrew thought

- Appendix C: Questions and answers

In this chapter, we answer questions that readers may have about the differences between idea-truth and person-truth.

Isn’t God subject to natural law?

Some Latter-day Saint scholars have argued that the personal, relational truth of the scriptures exists within a larger, fundamentally Greek-like universe. From this view, God’s power is based on his superior knowledge of abstract, universal scientific laws. For example, Elder Widstoe argued, “God is part of nature, and superior to it only in the sense that the electrician is superior to the current that is transmitted along the wire. The great laws of nature are immutable, and even God cannot transcend them.”((John A. Widstoe, Joseph Smith as Scientist (Heber City, UT: Archive Publishers, 2000), 138.))

Elder Parley P. Pratt suggested the laws that govern the physical world “are absolute and unchangeable in their nature, and apply to all intelligent agencies which do or can exist. They, therefore, apply with equal force to the great, supreme, Eternal Father of the heavens and of the earth, and to His meanest subjects.”((Parley P. Pratt, Spirituality: Key to the Science of Theology (Springville, UT: Cedar Fort, 2007), 25. He further wrote:

Among the popular errors of modern times an opinion prevails that miracles are events which transpire contrary to the laws of nature, that they are effects without a cause. If such is the fact, then, there never has been a miracle, and there never will be one. The laws of nature are the laws of truth. Truth is unchangeable, independent in its own sphere. A law of nature never has been broken. And it is an absolute impossibility that such a law ever should be broken. That which at first sight appears to be contrary to the known laws of nature, will always be found, on investigation, to be in perfect accordance with those laws.

Parley P. Pratt, Spirituality: Key to the Science of Theology (Springville, UT: Cedar Fort, 2007), 67.)) Elder B. H. Roberts wrote, “Miracles are not, properly speaking, events which take place in violation of the laws of nature, but … they take place through the operation of higher laws of nature not yet understood by man.”((B. H. Roberts, New Witnesses for God, vol. 1, (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret News, 1911), 249.))

This popular perspective seems to reconcile the person view of truth with the idea view of truth. However, this approach requires us to adopt the idea view of truth, and its Greek assumptions about the world. It subjugates the Hebrew worldview of scripture into a fundamentally Greek conceptual framework. As Garrard points out, “In such a universe it would be more reasonable for people to worship the law (which incidentally has no body, parts, or passions) since it is more powerful than God and he is subject to it.”((LaMar E. Garrard, “Creation, Fall, and Atonement,” in Studies in Scripture: Volume Seven: 1 Nephi to Alma 29, ed. Kent P. Jackson (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1987), 93.))

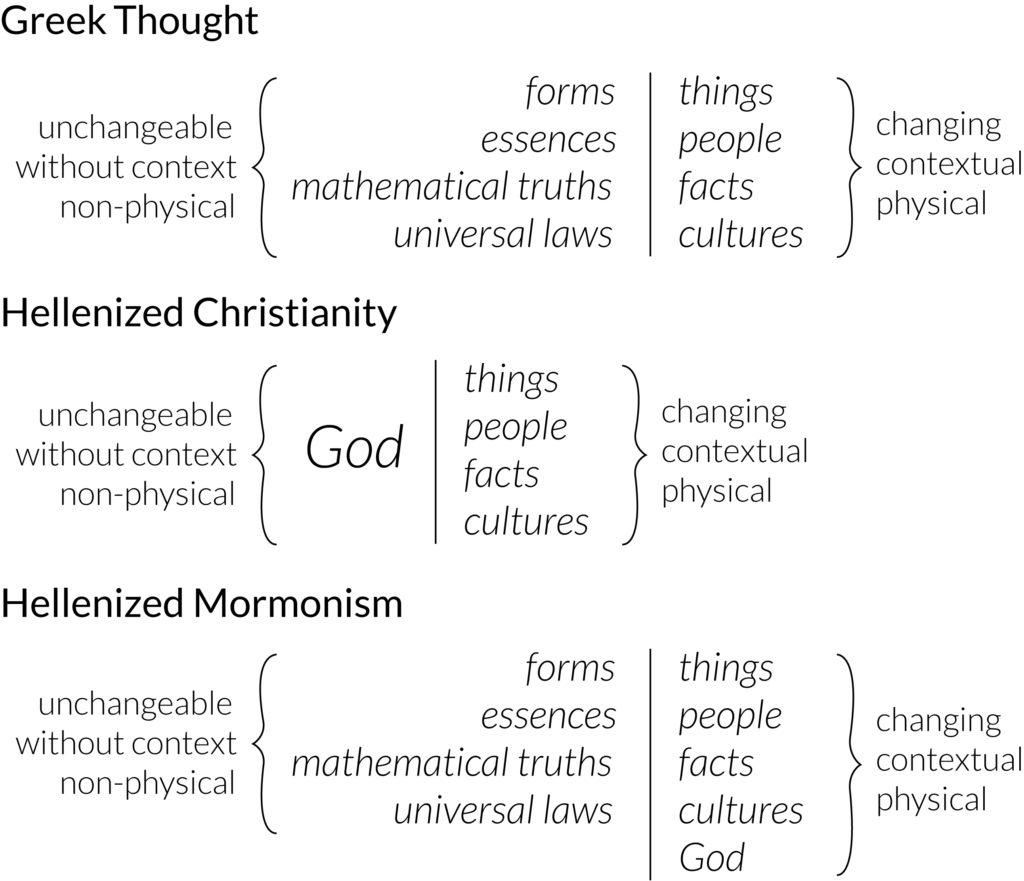

When we do this, we run the risk of creating a Hellenized version of a fundamentally Hebrew faith (which is what early Christian scholars did). In fact, this view adopts the same Greek philosophical ideas as Hellenized Christianity. Although it changes the conceptual category God occupies, it does not challenge any of its underlying assumptions about truth (see the figure on the next page). It embraces the Greek assumption that fundamental reality must be abstract and incorporeal.

We do not claim that those who hold this view are apostate, or leading the Church into apostasy. The inspired teachings of Elder Pratt, Elder Widstoe, and Elder Talmage can be taken in a different light. Their ultimate goal was to convince Latter-day Saints that they can pursue scientific endeavors and not relinquish their faith. As Brigham Young taught, “Our religion will not clash with or contradict the facts of science in any particular.”((Teachings of the Presidents of the Church: Brigham Young (Salt Lake City, UT: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1997), 197.)) This is vital message that has been repeated by nearly every prophet since.

In addition, prophets and apostles have been inconsistent on this issue. For evidence, we read that God “hath given a law unto all things, by which they move in their times and their seasons; [a]nd their courses are fixed, even the courses of the heavens and the earth, which comprehend the earth and all the planets” (D&C 88:42-43). This implies that God decreed natural law. Similarly, President Brigham Young taught:

It is hard to get the people to believe that God is a scientific character, that He lives by science or strict law, that by this He is, and by law he was made what He is; and will remain to all eternity because of His faithful adherence to law. It is a most difficult thing to make the people believe that every art and science and all wisdom comes from Him, and that He is their Author.((Brigham Young, Journal of Discourses, vol. 13, 306.))

At first glance, it seems that Brother Brigham agrees with Elders Pratt, Widstoe, and Roberts. But he is actually saying something very different. Brigham Young describes God as a “scientific character,” but then claims that God is the Author of scientific law. However, the scientific laws of Greek thought do not have authors. They are immutable, embedded in the fabric of the universe.

On another occasion, President Young taught: “Our religion embraces chemistry; it embraces all the knowledge of the geologist, and then it goes a little further than their systems of argument, for the Lord almighty, its author, is the greatest chemist there is.”((Brigham Young, Journal of Discourses, vol. 15, 127. ))But notice that God is not a chemist in the same way that we can be chemists (in mortality, at least), because chemists do not author the laws of chemistry. Brigham Young is teaching that God is familiar with and often works through scientific laws, but also implies (with imprecise language, perhaps) that such laws are decreed. The prophet Joseph Smith taught:

God has made certain decrees which are fixed and immovable; for instance, God set the sun, the moon, and the stars in the heavens, and gave them their laws, conditions and bounds, which they cannot pass except by His commandments; they all move in perfect harmony in their sphere and order, and are as lights, wonders and signs unto us.((Joseph Smith, History of the Church, vol. 4, 554.))

When Joseph Smith describes these laws as “fixed and immovable,” he is certainly not using these terms in the Greek sense. He implies that heavenly bodies could defy these laws when commanded by God. They are fixed and immovable only to us. Joseph Smith taught, “If the veil were rent today, and the great God who holds this world in its orbit, and who upholds all worlds and all things by his power, was to make himself visible … you would see him like a man in form—like yourselves.”((Joseph Smith, Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith, 345, emphasis added.)) In the Book of Mormon, we read:

For behold, the dust of the earth moveth hither and thither, to the dividing asunder, at the command of our great and everlasting God. Yea, behold at his voice do the hills and the mountains tremble and quake. And by the power of his voice they are broken up, and become smooth, yea, even like unto a valley. Yea, by the power of his voice doth the whole earth shake; Yea, by the power of his voice, do the foundations rock, even to the very center.

Yea, and if he say unto the earth—Move—it is moved. Yea, if he say unto the earth—Thou shalt go back, that it lengthen out the day for many hours—it is done; And thus, according to his word the earth goeth back, and it appeareth unto man that the sun standeth still; yea, and behold, this is so; for surely it is the earth that moveth and not the sun. (Helaman 12:8-17)

In conclusion, the physical universe does operate within a system of law. This system is detectable by empirical observation, but ultimately answers to God (who can override it).

What about Justice and Mercy in the Book of Mormon?

We often read these passages wrong, because we read them with Greek eyes. We import idea-truth assumptions into the text. Here is the passage in question (written by Alma to his son Corianton):

And thus we see that all mankind were fallen, and they were in the grasp of justice; yea, the justice of God, which consigned them forever to be cut off from his presence. And now, the plan of mercy could not be brought about except an atonement should be made; therefore God himself atoneth for the sins of the world, to bring about the plan of mercy, to appease the demands of justice, that God might be a perfect, just God, and a merciful God also. …

But there is a law given, and a punishment affixed, and a repentance granted; which repentance, mercy claimeth; otherwise, justice claimeth the creature and executeth the law, and the law inflicteth the punishment; if not so, the works of justice would be destroyed, and God would cease to be God. (Alma 42:14-15, 22)

It is easy to interpret these verses as talking about Justice and Mercy as abstract laws God Himself is beholden to (or “God would cease to be God”). When we take a person view of truth seriously, though, we can reread these scriptures. Alma uses the terms justice and mercy to depict two different states of the soul, or ways of being in relation with God. Justice refers to our separation or alienation from God: “And thus we see that all mankind were fallen, and they were in the grasp of justice; yea, the justice of God, which consigned them forever to be cut off from his presence” (Alma 42:14). Mercy refers to reconciliation with God.

Simply put, if sin is rebellion against God, we cannot be reconciled with God while sinning. Can we “rebel” against someone, and not be at odds with them (i.e., reconciled)? If we could be reunited with God while still living in the midst of sin, there would be no justice (that is, separation from God due to sin) in the first place. The concept itself would be meaningless. Alma describes this as “mercy destroying justice.” If sin really does alienate us from God, then mercy—that is, reunion and reconciliation with God—can only happen on conditions of repentance (that is, the cessation of sin and rebellion).

And that’s why we need Christ. Through the Atonement, Christ empowers us to change our ways, lay aside our sinful habits and lifestyles, and become new creatures in Christ. Without this, Alma teaches, “there was no means to reclaim men from this fallen state, which man had brought upon himself because of his own disobedience” (Alma 42:12). In this way, the Atonement brings about mercy (that is, reconciliation with God) while at the same time preserving justice (that is, alienation from God due to sin), by helping us return to God as changed people. Amulek taught the Zoramites:

And thus [Christ] shall bring salvation to all those who shall believe on his name; this being the intent of this last sacrifice, to bring about the bowels of mercy, which overpowereth justice, and bringeth about means unto men that they may have faith unto repentance.

And thus mercy can satisfy the demands of justice, and encircles them in the arms of safety, while he that exercises no faith unto repentance is exposed to the whole law of the demands of justice; therefore only unto him that has faith unto repentance is brought about the great and eternal plan of redemption. (Alma 34:15 -16)

It might be fruitful to read these verses in this way: “This is the intent of this last sacrifice, to initiate a reconciliation of man with God, with overpowereth the separation caused by sin and rebellion, because it bringeth about means unto men that they may have faith to change their lives and lay down their instruments of rebellion, and thereby restore their relationship with God.” Christ’s sacrifice does not so much appease the demands of cosmic law, as it invites us to change our ways and reconcile with God. In this way, it overpowers our separation from God due to sin, without undoing the very concept of sin and separation in the first place.

Why would God cease to be God, if sin did not separate us from Him? James Faulconer explains that in Hebrew thought, identity is bound up in activity. Things (or persons) are what they do. If something (or someone) changes what it does, it changes what it is, as well the relations it has with others. “Though God has a particular form,” he writes, “for Hebrew, to be God is not necessarily to have that particular form. To be God is not to fit under a particular logical, biological, or ontological category but to live and act in a particular way, namely, the godly way.”((James Faulconer, “Appendix 2: Hebrew versus Greek Thinking,” in Scripture Study: Tools and Suggestions (Provo, UT: BYU Press, FARMS, 1999), 141.))

So when Alma tells us that God would cease to be God if He were to cease holding us morally accountable for rebellion and pride, he may just be telling us something about what it means to be a God. Justice and mercy are ways in which our Heavenly Father acts as God. rather than Greek-like abstract laws independent of Him. He holds us accountable for our actions, and yet reconciles us with Him when we are willing. As Elder D. Todd Christofferson explains, “a God who makes no demands is the functional equivalent of a God who does not exist.”((D. Todd Christofferson, “Free Forever, to Act for Themselves,” Ensign, November, 2014, 16-19.))

If rebellion, pride, and enmity no longer alienated us from God, this would profoundly alter what it means for Him to be our God. He would no longer be the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.

Doesn’t the Book of Mormon describe God as unchangeable?

The ancient prophet Moroni wrote: “[D]o we not read that God is the same yesterday, today, and forever, and in him there is no variableness neither shadow of changing? And now, if ye have imagined up unto yourselves a god who doth vary, and in whom there is shadow of changing, then have ye imagined up unto yourselves a god who is not a God of miracles” (Mormon 9:9-10). And, somewhat further on, Moroni asks:

And who shall say that Jesus Christ did not do many mighty miracles? And there were many mighty miracles wrought by the hands of the apostles. And if there were miracles wrought then, why has God ceased to be a God of miracles and yet be an unchangeable Being? And behold, I say unto you he changeth not; if so he would cease to be God; and he ceaseth not to be God, and is a God of miracles. (Mormon 9:18-19)

From a Greek perspective, these passages seem to clearly refer a universal truth and the immutable nature of God. If we read the verses from this perspective, then we might conclude that if God’s servants deliver differing or conflicting instructions in two comparable contexts (which cannot be easily reduced to an abstract, universal principle), then one of those instructions is likely wrong.

However, these passages can be easily interpreted differently. In context, Moroni reiterates the fact that God is active in the world. He communicates with His children, performs miracles, bestows spiritual gifts, and so forth. We can interpret Moroni as arguing that a God who is not active in the world is a God that does not exist at all. To deny the revelations of God, to deny the existence of spiritual gifts and miracles is to deny the very existence of God as a living, personal, and relational being in the world. An inactive, theoretical God, whose hand is not manifest in our lives and communities, is not the living God of Israel.

The above passages (and others like them– see, e.g., Moroni 8:18, D&C 20:17, D&C 104:2) assure us that God is a thoroughly reliable, covenant-making and promise-keeping being. He does not betray His commitments to His children, and He does indeed have patterns that He frequently follows. He is neither fickle nor arbitrary. Jaroslav Pelikan, one of the most famous scholars of Christian history, has written:

In Judaism it was possible simultaneously to ascribe change of purpose to God and to declare that God did not change, without resolving the paradox; for the immutability of God was seen as the trustworthiness of his covenanted relation to his people in the concrete history of his judgment and mercy, rather than as a primarily ontological category.((Jaroslav Pelikan, The Christian Tradition: A History of the Development of Doctrine (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago, 1971), 22.))

God’s instructions do change from time to time, depending upon the circumstances and choices of His children. But He is nonetheless utterly and completely reliable in His promises, and unfailing in His redemptive activity towards those who serve Him.

Don’t the scriptures describe God’s commandments as “irrevocable”?

In the Doctrine and Covenants, we read, “There is a law, irrevocably decreed in heaven before the foundations of this world, upon which all blessings are predicated—And when we obtain any blessing from God, it is by obedience to that law upon which it is predicated” (D&C 130:20-21). In addition, many materials from the Church use the phrase “eternal law,” which implies support for an idea view of truth, where truth is expressed in abstract, universal, unchangeable ideas.

Many of God’s laws may be “irrevocable” by divine decree, and may have existed from before our mortal sojourn on Earth (“before the foundations of this world”)—but this does not mean that they are the same sort of immutable, metaphysical entities that the Greeks referred to as absolute truth. In addition, “irrevocable” may simply mean that God’s appointed laws cannot be revoked by man’s will or authority, or that God is committed to them and will not change them at a whim. God’s laws may be unchanging, but that does not mean they are unchangeable.

The Lord teaches us in the Doctrine and Covenants, for example, that eternal does not mean the same thing as “without end,” but rather represents one of the honorific names of God:

Nevertheless, it is not written that there shall be no end to this torment, but it is written endless torment. Again, it is written eternal damnation; wherefore it is more express than other scriptures, that it might work upon the hearts of the children of men, altogether for my name’s glory. Wherefore, I will explain unto you this mystery, for it is meet unto you to know even as mine apostles. …

For, behold, the mystery of godliness, how great is it! For, behold, I am endless, and the punishment which is given from my hand is endless punishment, for Endless is my name. Wherefore—Eternal punishment is God’s punishment. Endless punishment is God’s punishment. (D&C 19:6-12, emphasis added)

Perhaps we can say something similar about “eternal law.” Eternal law is God’s law, and that is why we damage our relationship with Him when we violate it. For example, LaMar E. Garrard suggests, “[Eternal law] is eternal only in the sense that ‘Eternal Law’ is God’s law for he created it and ‘Eternal’ is his name: it has a beginning and it may have an end, depending upon the circumstances.”((LaMar E. Garrard, “God, Natural Law, and the Doctrine and Covenants,” in Doctrines for Exaltation: Sidney B. Sperry Symposium, February, 1989 (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1989), 69.)) It is binding upon us by virtue of the fact that it is He who has commanded it.

Don’t modern prophets talk about moral law using Greek ideas?

Yes, modern prophets and apostles sometimes use the terms and forms of Greek thought to communicate their ideas. For example, Elder L. Tom Perry declared quite boldly: “God reveals to His prophets that there are moral absolutes. … Surely there could not be any doctrine more strongly expressed in the scriptures than the Lord’s unchanging commandments.”((L. Tom Perry, “Obedience to Law is Liberty,” Ensign, May, 2013, 86-88.)) This seems to present an idea view of truth, where truth can be expressed through statements of unchangeable, abstract law.

However, in this context, Elder Perry uses Greek language to express distinctly un-Greek ideas. He speaks of God as the author and source of the commandments. He expounds, “Sin will always be sin. Disobedience to the Lord’s commandments will always deprive us of His blessings.”((L. Tom Perry, “Obedience to Law is Liberty,” Ensign, May, 2013, 86-88.)) In other words, focus of our moral accountability is God, a divine person. This is an idea that is foreign to Greek thought.

Further, God’s commandments often do not change. Some instructions have remained the same from the beginning of time and will likely persist throughout all eternity. We must not harbor illusions that we can disregard God’s present commandments just because they are not the immutable entities of Greek truth. Ironically, to do so would not be adhering to Hebrew thought, but rather to Greek thought. It is Greek thought that teaches us to reverence only that which is immutable. We should treat God’s laws with the reverence warranted by the fact that they have been given by our Creator.

It is entirely unsurprising that prophets and apostles sometimes use the language of Greek thought in their sermons. After all, they speak English, a language of Indo-European descent, and are speaking to audiences who were also raised in the Western world and who respond positively to the language and norms of Greek thought. The language of Greek thought can communicate the weightiness and persistence of God’s law, and teach us what to expect of the future on many important issues. The language of absolutism can be a powerful tool against the insidious doctrines of moral relativism.

Does the person-view of truth lead to moral relativism?

No, it does not. It is Greek thought that treats moral relativism as the only alternative to moral absolutism. From a person view of truth, right and wrong are centered on God and His will for us. Hebrew thought grounded morality in our covenants with God (and His covenants with us). As Richards and O’Brien helpfully note:

Of course, relationships come with certain expectations. But if worldviews are like icebergs—with the dangerous part underwater—then in the first-century world that Paul and Jesus inhabited, relationships were the underwater part. Rules were the parts above the waterline. Rules didn’t (and, in many places, still don’t) describe the bulk of the matter; they merely described the visible outworking of an underlying relationship, which was the truly defining element.((E. Randolph Richards and Brandon J. O’Brien, Misreading Scripture with Western Eyes: Removing cultural Blinders to Better Understand the Bible (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2012), 161.))

In other words rules and moral principles still matter from a person view of truth. But they are surface level expressions of our deeper relationship with God.

Some will be concerned that this means that any action, no matter how violent or cruel, can become right if we think that God has commanded it. In fact, this is how violent extremists often justify murder. We have no desire to excuse them in the slightest. We do not have easy answers to these questions, except to point to Paul’s statement: “But the fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, longsuffering, gentleness, goodness, faith, Meekness, [and] temperance” (Galatians 5:22-23).

Any time our hearts are hardened with resentment or hate, we can guarantee that we are not acting on God’s behalf. Pride, anger, and malice towards God’s children alienate us from God. God is not going to instruct us to kill except in the direst circumstances. The more familiar we are with God’s ways, the more we realize this. We read, “neither doth [the Lord] will that man should shed blood, but in all things hath forbidden it, from the beginning of man” (Ether 8:19).

God’s instructions may not be the immutable abstractions of Greek thought, but detectable patterns do exist in God’s teachings (and at times strongly so). Our point is simply that from a person view of truth, abstract universals are not sufficient. In addition, we are not left without any metric for evaluating right and wrong—we have divine revelation, we have prayer, we have reason enlightened by the Holy Spirit. We also have tradition, when those traditions are informed by a culture that acknowledges God and His servants.

In addition, while we do not worship abstract ideas, we do worship a God of Truth. And that means that God is true. He is true to His promises, true to His children. And so while we can in theory imagine any of God’s commandments changing, some changes would be a violation of His promises to us, and so we can trust Him not to do that.