- Introduction

- What If Truth Is a Person?

- The Ancient Roots of Person Truth

- Faith in ideas, or faithfulness to a Person?

- Knowing God vs. believing ideas about Him

- Person-truth does not give us control

- Knowing Person-truth through covenant

- Our on-and-off relationship with Person-truth

- The arch-nemesis of Person-truth

- What it means to be an authority on truth

- What is sin, if truth is a Person?

- Rethinking the Atonement of Christ

- Person-truth in an age of science and reason

- Conclusion

- Appendix A: Further Readings

- Appendix B: More on Greek and Hebrew thought

- Appendix C: Questions and answers

The differences between idea-truth and person-truth can be mapped onto differences between ancient Greek and Hebrew thought. For many Greek philosophers, truth was abstract and impersonal, while in Hebrew thought, truth was more contextual and personal. These differences still matter today. Modern thought is influenced by the ideals of Greek philosophy. The brilliant mathematician and philosopher Alfred North Whitehead once wrote, “The safest general characterization of the [Western] philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato.”((Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2010), 39. It might also be accurate to characterize the intellectual history of the Western world as a centuries-long critical dialogue between Plato and Aristotle. For an excellent articulation of that viewpoint, see Arthur Herman’s excellent book The Cave and the Light: Plato versus Aristotle, and the Struggle for the Soul of Western Civilization (New York, NY: Random House, 2013).))

In contrast, the earliest Christian converts (during the apostolic ministry of Peter, James, and John) were more familiar with Hebrew thought. Old Testament scholar Norman H. Snaith wrote, “The Old Testament is the foundation for the New. The message of the New Testament is in the Hebrew tradition as against the Greek tradition. Our tutors to Christ are Moses and the prophets, and not Plato and the Academies.”((Norman H. Snaith, The Distinctive Ideas of the Old Testament (New York, NY: Schocken Books, 1964), 159.)) Another influential biblical scholar, John Dillenberger, has cautioned, “[T]o ignore Hebraic ways of thinking is to subvert Christian understanding.”((John Dillenberger, “Revelational Discernment and the Problem of the Two Testaments,” in Bernhard W. Anderson, ed., The Old Testament and Christian Faith (New York, NY: Herder and Herder, 1969), 160.))

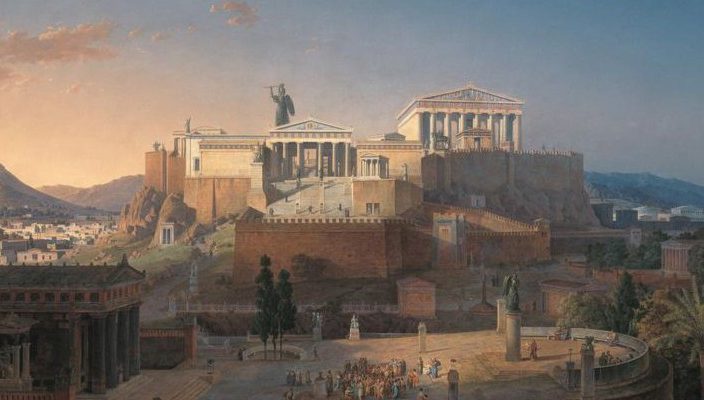

Greek Philosophy

The gods of Ancient Greece were very different than the God we find in scripture. The gods of Olympus were more like superheroes, larger-than-life embodiments of common human virtues and vices. Outside the occasional dalliance or bit of meddling, they were not interested in human affairs and seldom responded to people who worshipped them.((The distinguished philosopher Daniel Robinson explains, “The gods of Homer have their favorites among mortals and even occasionally breed with them, but in general the Olympians are preoccupied with their own affairs, often indifferent and even contemptuous of human lives and limitations.” From Daniel Robinson, An Intellectual History of Psychology (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1995), 16.)) When the philosophers of Athens heard Paul’s missionary message of a God who was compassionate and involved in human affairs, they responded by calling Paul a “babbler.” They said, “He seemeth to be a setter forth of strange gods: because he preached unto them Jesus, and the resurrection” (Acts 17:18).

For Greek philosophers, the quest for truth was more or less unrelated to the legends that were taught in the temples of the cities or at the hearthside in the home. It was not a quest to understand the intentions of divine persons. Rather, it was a quest to capture (via the intellect) certain rational principles or concepts. When Greek philosophers did believe in the traditional gods, they believed they operated within a broader universe that was governed by ideas. From the perspective of some, even the gods were bound by fate, and could not alter the dictates of impersonal, abstract law.((Daniel Robinson explains further:

[The gods of the Greeks] must be propitiated, never aroused to anger or envy. But they are also not looked to for answers to the abiding questions or for solutions to the problems of life and mind. In the matter of fundamental truths and their implications, we are left to our own devices, for, in these matters, the gods themselves are limited. Even the mighty Zeus must consult the fates if he would know the end result of his designs.

From Daniel Robinson, An Intellectual History of Psychology (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1995), 17.)) In this way, truth was distinct from any god who could carry on a dialogue with mortals.((Even Plato’s Demiurge – a sort of artisan God who fashioned the world out of a chaos of pre-existing materials – was thought to be of a lesser order of perfection than the Eternal Forms, a knowledge of which the Demiurge employed in the creation of the world. See Francis M. Cornford, Plato’s Cosmology (Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing Company, 1997).))

The ancient Greeks were fascinated with things that do not change. Greek philosophers often disagreed with each other, but they almost always saw things that do not change as more fundamental than things that do change. James Faulconer wrote, “[The Greeks] believed that change is a defect, that whatever is ultimate must be static and immobile. What changes, including the world that we experience, is of a lesser order than what does not change.”((James Faulconer, Scripture Study: Tools and Suggestions (Provo, UT: BYU Press, FARMS, 1999), 136.)) For this reason, they also saw things that are abstract as more important than things that are particular to a specific context, and things that are outside space and time as more valuable than things that are physical and temporal. Greek philosophers analyzed and categorized objects (specific people, places, or things) in terms of unchanging characteristics, rather their specific contexts or features.

Plato (427-347 BC), for example, distinguished between the substance and the essence of things. The substance of a table can change. A table can be brown or black, plastic or wood, varnished or scratched, all while still being a table. However, the essence of a table cannot change (without becoming something else instead). For example, something is not a table if it is not somewhat flat and raised off of the ground, or if we cannot place objects on it. These attributes are essential to the idea of a table. For Plato, this world of essences is where we find truth.

Pythagoras of Samos (ca. 570 – ca. 495 BC) believed that truth could be found in mathematics, and that the physical world conformed to universal mathematical laws.((Jeffrey C. Leon, Science and Philosophy in the West (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1999).)) From his perspective, before we can understand the world, we must discover the mathematical realities that govern it. Mathematics has the kind of consistency we would expect if fundamental truth is unchangeable. The Pythagorean Theorem (a2 + b2 = c2) holds true for every right triangle in every context, and is just as true today as it was in the days of Pythagoras.((Well, not exactly. The Pythagorean Theorem only holds true for Euclidean geometry (that is, the geometry of planes). It breaks down entirely in non-Euclidean geometries (such as on a globe). This illustrates the main idea of this book: how the world looks and what counts as truth depends on our starting point.))

Aristotle (384 – 322 BC) focused his attention on the material world, in addition to the world of ideas. He argued that we must ground all of our theorizing in the stubborn facts of physical reality and sensory experience. Aristotle believed that universal laws govern the world, and that they will manifest in the predictable operations of the physical universe. To discover truth, from his view, we must carefully observe the world and detect these patterns. Aristotle pointed Western philosophy towards empirical observation (as opposed to philosophical speculation) as the foundation of modern science.((For an engaging look at Aristotle’s influence down through the ages, and most especially in our modern era, see Arthur Herman, The Cave and the Light: Plato versus Aristotle, and the Struggle for the Soul of Western Civilization (New York, NY: Random House, 2013).))

As different as their ideas were, each of these philosophers emphasized the importance of non-change. With few exceptions, the ancient Greeks believed that anything that changes is subservient to a higher order that does not change.((Some might suggest that Heraclitus (535 B.C. – 475 B.C.) is an exception. He is famous for having claimed that “everything flows” and “a man cannot step into the same stream twice.” Heraclitus emphasized the universality of change. However, this exception simply highlights the rule. According to Boman, for example, “This high estimate of change and motion is un-Greek; Heraclitus stands alone among Greek philosophers with his doctrine.” In addition, Heraclitus postulated an unchanging logos that governed change in the world, and so some do not consider him an exception at all.

Further, Heraclitus’s expression of his ideas was labored and difficult, largely because “the Greek language which, unlike Hebrew, was not capable of giving adequate expression to such ideas.” Plato himself said of Heraclitus and his ideas, “The maintainers of this doctrine have as yet no words in which to express themselves, and must get a new language.” See Thorleif Boman, Hebrew Thought Compared with Greek, trans. Jules L. Moreau (New York, NY: Norton, 1960), 51-52.)) For that reason, ultimate truth in the Greek worldview is whatever is fundamentally unchangeable—whether we are talking about the natural world or human morality.((Noel Reynolds explains this idea well:

One of the most fundamental and perennially attractive contributions of early Greek thinkers was the concept of nature—the idea that behind all the variety and vagaries of human experience there might be a solid, regular, and permanent reality. Nor did they limit this insight to the physical and material world, but rather they also glimpsed (or diligently sought) the possibility of finding ultimate truth in matters pertaining to human morality and the good.

Noel B. Reynolds, “The Decline of Covenant in Early Christian Thought,” in Noel B. Reynolds, ed., Early Christians in Disarray: Contemporary LDS Perspectives on the Christian Apostasy (Provo, UT: BYU Press, FARMS, 2005), 309.)) For the ancient Greeks, the genuine truth-seeker sifts through the dynamic variety of life and looks for whatever is the same in every place, every time, and every context.

Hebrew Thought

In this book, we use the term Hebrew thought rather than Hebrew philosophy. This is because the ancient Hebrews did not engage in the same sort of formal scholarly dialogue the Ancient Greeks did. Rather, the ancient Hebrews explored the same questions through the concrete matters of everyday living. Further, unlike the Greeks, the Hebrews did not place as much emphasis on non-change.

This can be seen in differences between the Hebrew and the Greek languages: Greek tends to focus on what is static and unchanging (the nouns), while Hebrew tends to focus on what is in motion (the verbs).((James Faulconer wrote, “Though Indo-European (hereafter referred to as Greek) languages focus on the static when concerned with what ultimately is, Semitic (hereafter referred to as Hebrew) languages focus on the temporal (but they mean something different by time) and dynamic.” James Faulconer, Scripture Study: Tools and Suggestions (Provo, UT: BYU Press, FARMS, 1999), 136.)) This difference has filtered into modern-day English. Biblical scholar Marvin Wilson provides us with an example:

The English language usually places the noun or subject first in the clause, then the verb or action-word; for example, ‘The king judged.’ In the narrative of biblical Hebrew, however, the order is normally the reverse. That is, the verb most often comes first in the clause, then the noun; thus, ‘He judged, (namely) the king.’((Marvin Wilson, Our Father Abraham: The Jewish Roots of the Christian Faith (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1989), 137.))

In Hebrew thought, nouns are not static objects, but are associated with action of some kind. What something does defines what it is. A car, for example, might be something that transports people from one place to another. If it no longer does that, it is no longer a car. A rusted car found half buried in the woods is an artifact (something that reveals the past), but has stopped being a car.((This is a fictional example we invented to illustrate how Hebrew’s action-oriented thought differs from Greek thought’s essences and substances.))

In English, we often use verbs that convey abstract ideas, such as “love,” “hate,” or “anger,” that cannot be directly observed. In contrast, the Hebrew language uses concrete imagery and action words to convey abstract ideas. Marvin Wilson provides a number of examples. In Hebrew writing, “[to] ‘look’ is ‘lift up the eyes’ (Gen. 22:4); ‘be angry’ is ‘burn in one’s nostrils’ (Exod. 4:14); ‘disclose something to another’ or ‘reveal’ is ‘unstop someone’s ears’ (Ruth 4:4) … ‘stubborn’ is ‘stiff-necked’ (2 Chr. 30:8; cf. Acts 7:51).”((Marvin Wilson, Our Father Abraham: The Jewish Roots of the Christian Faith (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1989), 137.)) Similarly, as Hebrew scholar George Adam Smith explains, “Hebrew may be called primarily a language of the senses. [Words] originally expressed concrete or material things. … Only secondarily and in metaphor could they be used to denote abstract or metaphysical ideas.”((George Adam Smith, “The Hebrew Genius as Exhibited in the Old Testament,” in The Legacy of Israel, ed. Edwyn R. Bevan and Charles Singer (Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press, 1944), 10.))

Because the Hebrew language focuses so heavily on the concrete and tangible, Faulconer noted that, “Unlike Greek, Hebrew does not conceive of anything immaterial or unembodied, even in thought.”((James Faulconer, Scripture Study: Tools and Suggestions (Provo, UT: BYU Press, FARMS, 1999), 137.)) Indeed, Faulconer suggests, the idea of the immaterial may even be “required to believe that ultimate reality is absolutely static.”((James Faulconer, Scripture Study: Tools and Suggestions (Provo, UT: BYU Press, FARMS, 1999), 137.)) For this reason, the Hebrews seldom (if ever) focused on abstract or universal ideas the way that ancient Greek thinkers often did.((Expanding on this point, the philosopher William Barrett has taught:

Hebraism contains no eternal realm of essences, which Greek philosophy was to fabricate. … Such a realm of eternal essences is possible only for a detached intellect, one who, in Plato’s phrase, becomes a ‘spectator of all time and all existence.’ This ideal of the philosopher as the highest human type—the theoretical intellect who from the vantage point of eternity can survey all time and existence—is altogether foreign to the Hebraic concept of the man of faith who is passionately committed to his own mortal being. Detachment was for the Hebrew an impermissible state of mind, a vice rather than a virtue.

William Barrett, Irrational Man: A Study in Existential Philosophy (New York: Anchor Books, 1990), 76.)) Wilson explains, “For [the Hebrews], truth was not so much an idea to be contemplated as an experience to be lived, a deed to be done. … Thus their language has few abstract forms.”((Marvin Wilson, Our Father Abraham: The Jewish Roots of the Christian Faith (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1989), 137.))

In stark contrast with Greek philosophy, there is virtually no search for truth that is distinct from the search for God in Hebrew literature. To the extent that Hebrew thinkers did hold abstract ideas, they rarely elevated them to the realm of “truth” in a way that rivaled or transcended God. The Hebrews focused on their covenant relationship with God, and any intellectual journey that did not end with the living God of Israel was a journey in the wrong direction. Indeed, as Wilson pointedly observes, “the dynamic, active presence of the living God is one of the most central unifying themes of the Hebrew Bible.”((Marvin R. Wilson, Exploring our Hebraic Heritage: A Christian Theology of Roots and Renewal (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2014), 24.))

For the Hebrews, a God who does not judge and intervene in the world is a God who does not meaningfully exist. Even the name Yahweh (Jehovah), which can be interpreted to mean, “I will be there (for you),” implies both activity and relationship.((Gerhard von Rad, Old Testament Theology, vol. 1, trans. D. M. G. Stalker (New York, NY: Harper and Row, 1962), 190.)) God’s identity and being is defined by His activity towards us. Interestingly, the Hebrew word for truth is emeth, which means “faithfulness, firmness, reliability.” In Deuteronomy, we read, “He is the Rock, his work is perfect: for all his ways are judgment: a God of truth and without iniquity, just and right is he” (Deut. 32:4). The God of Israel is a God of truth because He is without iniquity or betrayal.

In short, the Hebrew perspective does not elevate abstract or impersonal ideas to the realm of the Divine because abstract ideas, by their very nature, cannot act in the world—they do not do, change, or influence in the world in any way. For the Hebrews, the God of Israel actively engages with the world, and the world is constantly influenced (and changed) by God’s activity. Thus, in a Hebrew worldview, abstract ideas are always one step removed from His relationship with us in the world.

Because ancient Greek philosophers focused on the abstract, they strove for rational and intellectual perfection, logical certainty, and the systematic representation of impersonal truth. In contrast, the Hebrew thinker strove for a concrete relationship with God and specific moral guidance in specific moral contexts. Most importantly, the Hebrews did not determine right conduct by looking for abstract, universal moral laws, but by consulting the commitments they had made to God and what He has commanded of them. Hebrew morality was shaped by the specific instructions that God gave to Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Moses, and others.

In other words, the idea of covenant was central to Hebrew thinking and practice. The Hebrews thought of these covenants as specific commitments made with God by a particular people at a particular place and time.((This emphasis on the particular distinguishes Hebrew ways of thinking from Greek philosophical approaches. Thomas Cahill explains this crucial difference:

Everything about the core values of the Jews and Christians was foreign to the Greeks and Romans, who in their philosophy had decided that whatever is unique is monstrous and unintelligible … only that which is forever is truly intelligible and worthy of contemplation. The ideal is what is interesting; the individual is beside the point.

In contrast, for the Hebrews, the particular and the contextual was of vital interest instead. Thomas Cahill, Sailing the Wine-Dark Sea: Why the Greeks Matter (New York, NY: Doubleday, 2003), 259.)) This is why history was deeply important to the Hebrews. The Hebrews valued a strict remembrance of God’s covenants with man, often through physical rituals (such as animal sacrifice, ritual cleansing) and communal practices (such as annual feasts and celebrations). These rituals and celebrations preserved in their collective remembrance the promises of God and their commitments to Him.

We can illustrate the difference between Greek and Hebrew thought by comparing Aesop’s fables with the parables of Jesus. Aesop (620-564 BC) was an Ancient Greek storyteller who told tales that involved talking plants or animals (such as the Tortoise and the Hare, or the North Wind and the Sun). Aesop’s fables were meant to teach moral lessons (usually to children) through stories. The “moral of the story” is usually expressed as a universal maxim or moral principle, and is far more important than the story itself. The story is merely a way to illustrate the idea in a memorable way.

In contrast, the parables of Jesus express more than universal maxims or abstract principles. In fact, Jesus’s Hebrew audience may not have universalized the lessons of a parable at all. The meaning depends on the life circumstances of the hearer. For example, consider the parable of the prodigal son: Sometimes we are the son, other times we are the father, and other times we are the elder brother. In the parable of the lost sheep, sometimes we are the ninety and nine, and other times we are the lost sheep. At yet other times, we are the shepherd.

Parables introduce narratives that we can live and relive in different ways in the unfolding situations of our lives. All of sacred scripture is the same: passages that mean one thing to a rebellious teenager may have a different meaning for a new parent, and still yet a different meaning for a bereaved spouse. The message cannot be universalized or summarized as a list of principles to follow. The particulars of the story matter, and are meant to be carried with the hearer (or reader) into his or her varying contexts.

For example, Nephi “likened” the scriptures to his situation by comparing his family’s experience to the story of Moses and the children of Israel, and their struggle to escape the bondage of Pharaoh. He did not sit down and reason out some sort of universal, abstract principle based on Moses’s experience. Rather, he saw himself and his family as the Israelites, Jerusalem as Egypt, Laban as pharaoh, and their journey as from captivity, through the wilderness, towards a land of promise. He brought the story, with all of its rich detail and nuance, into his context.

There is danger in “summarizing” Hebrew thought. But it is safe to contrast Greek philosophy’s focus on the abstract and universal with Hebrew thought’s focus on the particular the concrete. The Greeks valued things that do not change; Hebrew thought emphasizes that which is dynamic and active. In addition, the Greeks separated the idea of truth from the idea of personal, acting God, while Hebrew thought does not. In Hebrew thought, abstract ideas are less important than our relationship with the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.

Apostasy and Restoration

A few hundred years of Christ’s death, the “fullness” of the Gospel of Jesus Christ was no longer taught or practiced in its original, pristine form. Latter-day Saints often refer to this as the Great Apostasy. This apostasy was (at least in part) due to those within the Church who relied on philosophy and reason in lieu of ongoing revelation. Elder Dallin H. Oaks taught that, following the death of Christ, “there came a synthesis of Greek philosophy and Christian doctrine in which the orthodox Christians of that day lost the fullness of truth about the nature of God and the Godhead.”((Dallin H. Oaks, “Apostasy and Restoration,” Ensign, May 1995, 84.))

Many scholars refer to this process as the “Hellenization” of Christianity. Because Greek language and culture were profoundly different from Hebrew language and culture, this changed the way scriptural truth was understood. As Thorleif Boman explains:

Christianity arose on Jewish soil. … As the New Testament writings show, [Jesus and His apostles] were firmly rooted in the Old Testament and lived in its world of images. Shortly after the death of the Founder, however, the new religious community’s centre of gravity shifted into the Greek-speaking Hellenistic world. … Not only are these two languages essentially different, but so too are the kinds of images and thinking involved in them. This distinction goes very deeply into the psychic life; the Jews themselves defined their spiritual predisposition as anti-Hellenic.((Thorleif Boman, Hebrew Thought Compared with Greek, trans. Jules L. Moreau (New York, NY: Norton, 1960), 17.))

This development was accelerated by thinkers who wished to reconcile Christian teaching with the commonly accepted Greek ideas of their contemporaries.((For example, Noel Reynolds explains:

[A]lready in apostasy, the third-century Christians were in deep trouble. Official persecutions were increasing. They were plagued by a rapidly multiplying diversity of Christian doctrines and sects—each claiming to be the true heir of Christ and the apostles. There was no central leadership to help them distinguish between the true and the false. … Threatened with the utter demise of Christianity, they turned to well established and widely admired principles of Greek philosophy for a solution.

Noel B. Reynolds, “What Went Wrong for the Early Christians?” In Noel B. Reynolds, (Ed.), Early Christians in Disarray: Contemporary LDS Perspectives on the Christian Apostasy (Provo, UT: BYU Press, FARMS, 2005), 12.)) As early Christians adopted Greek assumptions, they reshaped their understanding of God in far-reaching ways. Because Greek thought prioritizes the abstract and unchangeable, Christian scholars began to think of God as immutable, an abstract being without body, parts, or passions who exists outside space and time, everywhere and yet nowhere at all.((Religious scholar Henry Jansen explains that, over time, Christian thinkers and theologians increasingly “borrow[ed] a number of fundamental concepts from Greek philosophy, viewing the philosophies of Plato and Aristotle as most nearly approximating the Bible and using it extensively for the conceptualization of the biblical depiction of God.” From Henry Jansen, Relationality and the Concept of God (Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Rodopi, 1995).)) Elder Oaks taught:

In the process of what we call the Apostasy, the tangible, personal God described in the Old and New Testaments was replaced by the abstract, incomprehensible deity defined by compromise with the speculative principles of Greek philosophy. … In the language of that philosophy, God the Father ceased to be a Father in any but an allegorical sense.((Dallin H. Oaks, “Apostasy and Restoration,” Ensign, May 1995, 85.))

The result was that the dynamic, living, passionate, caring, and embodied God described in the pages of Old and New Testament (and the Book of Mormon) was replaced by the sort of abstract, unembodied, and timeless entity described in the pages of Plato, Aristotle, and other Greek philosophers.

In this way, the God who could weep with his loved ones at the tomb of Lazarus (John 11:35), the God who “groaned within himself” and was “troubled because of the wickedness of the house of Israel” (3 Ne. 17:14), and the God whose joy could be full as he called little children to him and blessed them “one by one,” weeping yet again (3 Ne. 17:21), became a thing of the primitive past. By the time of the Reformation, the Western world had moved so far away from the living God of the Bible that Martin Luther argued that, even though “God is represented [in the Bible] as being angry, in a fury, hating, grieving, pitying, repenting,” nothing of the sort “ever takes place in him.”((Martin Luther, Bondage of the Will, trans. Henry Cole (New York, NY: Feather Trail Press, 2009), 33.))

In short, Latter-day Saints have good reason to be suspicious of Greek philosophy. For example, James Faulconer argues that “Greek … models of thought cannot do justice to the true and living God.”((James Faulconer, “Appendix 2: Hebrew versus Greek Thinking,” in Scripture Study: Tools and Suggestions (Provo, UT: BYU Press, FARMS, 1999), 136, italics added.)) In fact, he argues that because of the prevalence of Greek thought in the Western world, “[M]ost of what passes for talk about God, whether positive or negative, is talk about a god who is not the God of Israel,”((James Faulconer, “Appendix 2: Hebrew versus Greek Thinking,” in Scripture Study: Tools and Suggestions (Provo, UT: BYU Press, FARMS, 1999), 137.)) nor the God who appeared to Joseph Smith in the Spring of 1820.

As Latter-day Saints, we believe that Christ’s Church has been restored in our day through modern revelation. We believe that God the Father and His Son Jesus Christ visited Joseph Smith and anointed him to be a prophet and a spokesman, just as they had anointed Moses, Samuel, and Saul of Tarsus before him. And, in that moment (and on other occasions), Joseph Smith observed the physicality and living concreteness of God as the Father and the Son counseled with him face-to-face, and gave instructions in a particular place and at a particular time—as well as for a particular place and particular time.

Through Joseph Smith, God re-established the original apostolic Christian church, complete with divinely appointed prophets and apostles who have been commissioned to officiate covenants with God through sacred ordinances. Joseph Smith was also instrumental in restoring our understanding of God as the concrete, embodied, and relational being worshipped by the ancient Israelites.((Indeed, the evidence seems so compelling that it has led at least one LDS thinker to claim, “Twenty-first Century Mormons and Hebrew Christians at the meridian of time are one and the same.” From David Thomas, Hebrew Roots of Mormonism (Springville, UT: Cedar Fort, 2013), 247.))

For example, the Book of Mormon prophet Nephi declared: “[T]he fulness of mine intent is that I may persuade men to come unto the God of Abraham, and the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob, and be saved” (1 Nephi 6:4). Likewise, Moroni testified of “a God of miracles, even the God of Abraham, and the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob; and it is that same God who created the heavens and the earth, and all things that in them are” (Mormon 9:11). The scriptures of the Restoration (the Book of Mormon, the Doctrine and Covenants, and the Pearl of Great Price) thoroughly depict God as the person-truth we described in the previous chapter.