|

| What kinds of unintended errors can arise when we conflate the two types of spiritual death? |

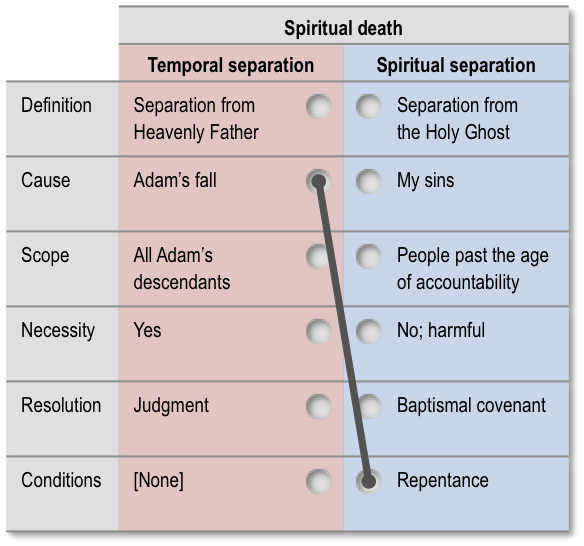

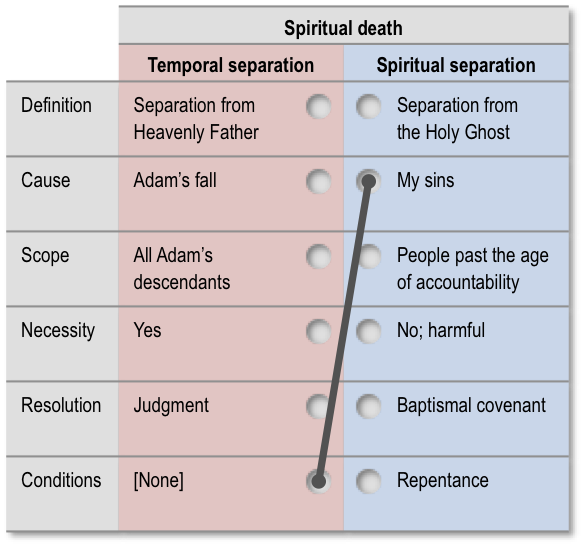

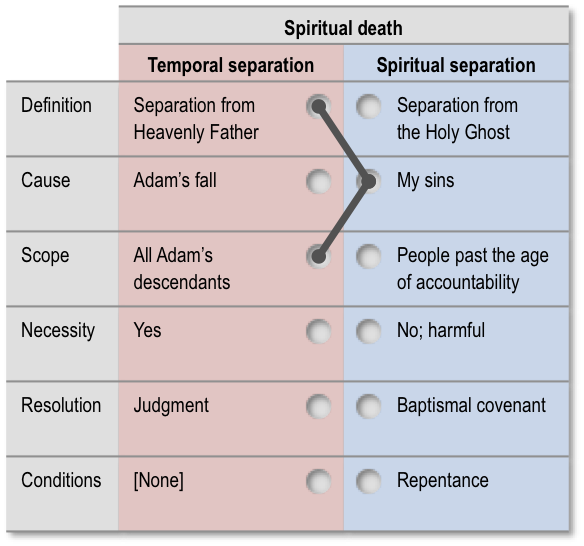

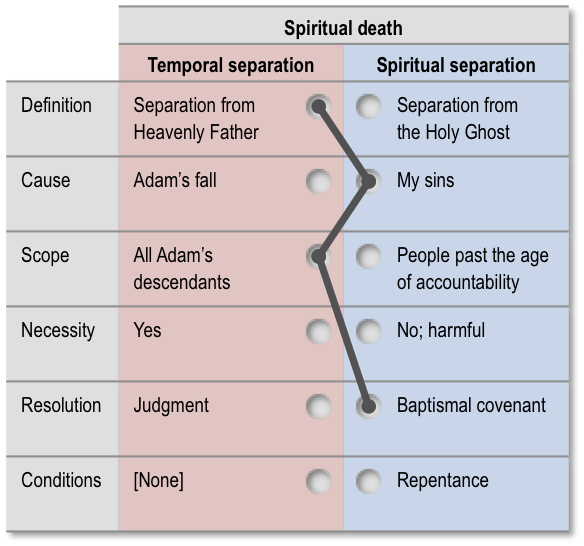

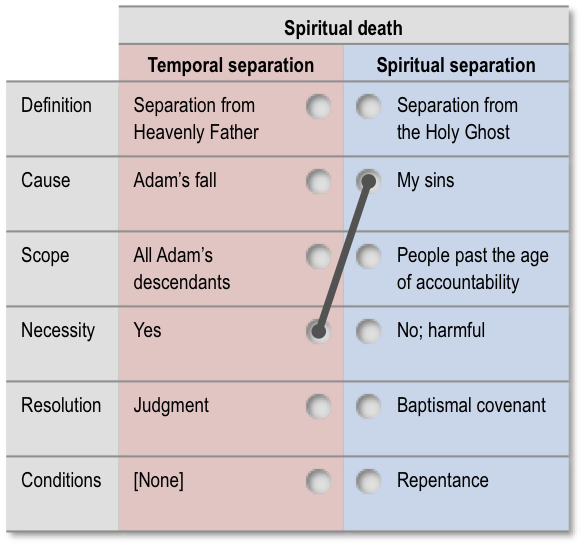

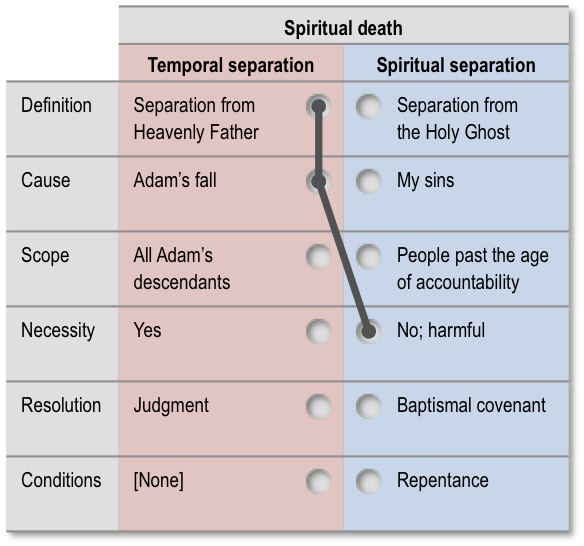

| Recap: Many explanations of spiritual death ignore the distinction between the two kinds of separation, mixing elements of one kind (e.g., cause) with elements of the other (e.g., conditions). |

The Inaccurate or Unclear explanations that I discussed in “Spiritual Death Quiz: My Answers” frequently treated the two kinds of spiritual death as though they were one entity. The problem with combining the temporal and spiritual separations into one concept is that doing so often conflicts with several important doctrines.1

Following are six erroneous ideas that are closely related to a conflated view of spiritual death. I do not necessarily think that these false notions grow directly out of the incorrect view of spiritual death, but I do think they’re related. It seems to me that failing to distinguish between the two types of spiritual death makes it far easier to fall into these doctrinal snares.

The first two errors are paired opposites. They both consist of mixing up the conditions required to overcome spiritual death, resulting in the idea of either (1) an unjust God who punishes us for things we didn’t do, or (2) a universalist God who saves everyone in their sins.

1. An Unjust God

As I’ve mentioned (see “Temporal Separation versus Spiritual Separation“), Elder Lund points out that if we say spiritual death is caused by Adam, but is only overcome if we make certain choices, such a formulation would negate God’s fairness as described in the second article of faith.

I must add one caveat. I’ve found that in most cases, if the speaker does not explicitly distinguish between two types of separation, they usually turn out to be talking about the spiritual separation. For example, the manual Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Joseph F. Smith has two paired chapters that are named on the basis of conditionality. Chapter 10 is titled “Jesus Christ Redeems All Mankind from Temporal Death†and chapter 11 is titled “Jesus Christ Redeems the Repentant from Spiritual Death.†While it overlooks the temporal separation, the title of chapter 11 is still technically accurate, as long as readers understand that it is referring to only one kind of spiritual death.

In the latter chapter, Joseph F. Smith lists the conditions for overcoming spiritual death:

The Gospel was, therefore, preached to him [Adam], and a way of escape from that spiritual death given unto him. That way of escape was through faith in God, repentance of sin, baptism for the remission of sins, the gift of the Holy Ghost by the laying on of hands. Thereby he received a knowledge of the truth and a testimony of Jesus Christ, and was redeemed from the spiritual death that came upon him.2

Is President Smith making the doctrinal error that Elder Lund warns against? Is President Smith saying, “Spiritual death is caused by Adam, but is only overcome if we make certain choices”? I don’t think so. Remember, in addition to Adam and Eve’s temporal fall, they each individually sinned and experienced their own individual spiritual separation, which they needed to repent of in order to overcome. It seems to me that President Smith is saying here that Adam and Eve needed to repent in order to overcome the spiritual separation. I believe statements like this are best considered a simplified description that is bracketing the temporal separation.

2. Universalism

The opposite of the unjust God error is the idea of a permissive God. It’s technically true to say, “Spiritual death is overcome unconditionally, no matter what choices you make” … if the speaker clarifies they were talking about the temporal separation. Otherwise, such statements could be construed as asserting the false idea that our sins are overcome unconditionally. For example, the fifth quote on the quiz says, “The first spiritual death does not begin for an individual on the earth until the age of accountability [when we sin]. … Christ’s Atonement … overcomes the first spiritual death by making it possible for all men and women to come into God’s presence to be judged.” To say that spiritual death is caused by individual sin, but everyone overcomes spiritual death and returns to God’s presence unconditionally, could unintentionally sound like a kind of universalism that is inconsistent with the restored gospel.3

Universalism is the false doctrine “that all human beings will eventually be saved.”4 Nephi specifically warned against it (2 Ne. 28:8), but it is still taught today by such groups as Universalists and Unitarians. I don’t know that this undifferentiated concept of spiritual death is the reason such groups teach this problematic doctrine, but it seems to me that it might be easier to make this error if you don’t know the doctrine that there are two types of spiritual death.

3. Original Sin

The third error is related to the cause and scope of spiritual death. If a person did not understand the two distinct kinds of separation, they might have a train of thought that sounded like this:

“Spiritual death is separation from God.”

[True.]

“Spiritual death is caused by sin.”

[True of the spiritual separation.]

“Little infants are obviously separated from God.”

[True of the temporal separation.]

“Therefore, little infants must be sinful. It’s the only explanation for why they’d be separated from God.”

[False.]

Because much of the rest of Christianity does not recognize a difference between the two types of spiritual death, that is exactly the conclusion they often come to. Many biblical passages are misunderstood to teach that children are actually born sinful and thus subject to the spiritual separation. For example, one Protestant author says,

Children, no matter how young, are not “innocent†in the sense of being sinless. The Bible tells us that even if an infant or child has not committed personal sin, all people, including infants and children, are guilty before God because of inherited and imputed sin. Inherited sin is that which is passed on from our parents. … The very sad fact that infants sometimes die demonstrates that even infants are impacted by Adam’s sin, since physical and spiritual death were the results of Adam’s original sin. Each person, infant or adult, stands guilty before God; each person has offended the holiness of God.5

If a person really believes that physical death is caused by sin, then the only way to explain why children die is to conclude that they are sinful.

4. Infant Baptism

This leads to a fourth error, which is related to how spiritual death is resolved. The belief that infants are “guilty before God†and spiritually dead through sin logically implies that they need to be spiritually reborn through baptism. This is a reason that many Christian religions teach the need for infant baptism. The Catholic catechism holds that

born with a fallen human nature and tainted by original sin, children also have need of the new birth in Baptism to be freed from the power of darkness. … Parents would deny a child the priceless grace of becoming a child of God were they not to confer Baptism shortly after birth.6

Thus, when people assume that anyone who is temporally distanced from God’s physical presence is also spiritually alienated from His influence, it is understandable that they conclude this separation is caused by sin and needs to be resolved through baptism.

As Mormon makes clear in Moroni 8, these are incorrect conclusions. He strongly denounces infant baptism and the idea that it would even be necessary. This misunderstanding can be greatly alleviated simply by distinguishing between the two spiritual deaths.7 Any passages referring to Adam passing on spiritual death to his descendants can be understood as referring to the temporal separation (or to the fact that the spiritual separation was now made possible because his descendants now had knowledge of good and evil).

5. Theistic Amorality

The fifth and sixth errors are another set of paired opposites. They are related to the question of whether spiritual death is necessary to progress. For lack of better terminology, I will call these errors (1) theistic amorality and (2) incomplete theodicy.

By amorality, I mean more than the secular/humanist idea that, since there is no God, there is no revealed scripture, and therefore no commandments to breaks, and thus nothing is a sin. That idea is to be expected among atheists such as Korihor, who said that “whatsoever a man did was no crime” (Alma 30:17). But I’m talking about a theistic version of this idea which accepts the existence of God, canonical scriptures, and divine commandments. In essence, it gives a token nod to the fact that God gives certain Thou-shalts and Thou-shalt-nots, but holds that in practical reality, sometimes we need to ignore those in order to grow. The line of thinking goes like this:

Sin has very unpleasant consequences.

[True.]

But I learn so much in the process of repentance …

[True, because the Lord is merciful enough to atone for our sins.]

… that it must have been necessary for me to commit those sins in order to learn those lessons.

[False.]

In fact, the more I look back on my life, the more I realize that all those things I called “sins” were really just “mistakes.” And don’t we need to make mistakes in order to learn?

This is a very seductive line of reasoning, in part because it actually seems to make sense of some of our experiences in life (see the series The Path of Sin for a detailed response to it). It is a very common idea among New Age groups, and it has even filtered into some branches of Christianity. The more extreme versions completely deconstruct the concept of sin, while still quoting from the Bible and professing faith in Jesus Christ. The following quote is from a proponent of the book A Course in Miracles, which completely changes the gospel message:

The good news is not that we sinned but can be forgiven. The good news is that we never sinned. We are incapable of sinning. “Sin is impossible.” Sin, like the unicorn, is a concept which we all carry in our minds yet which does not actually exist in reality. Not only have we not sinned, no one ever has and no one ever will. It simply is not in our nature to do so. The Course flatly states, “Sin does not exist.” …

This is a radical point of view, one which may take us a long time to accept, if we accept it at all. My teaching partner, Allen Watson, found that for him this was perhaps the single most objectionable idea in A Course in Miracles. He wrestled with it for years. Accepting that there is no sin can feel like a betrayal of God. Yet I believe it is an acknowledgment of God, of His absolute sovereignty. Sin is not the Will of God, and His Will is all-powerful. There is no sin, because God is God. The innocence we thought we lost has never been tainted.8

I once had a conversation with a relative who believes this. He said that everything that happens is meant to be, because the universe wants us to learn something from it, so we should just accept whatever we do. I agreed that we could learn from any circumstance, but I would stop short of saying that that fact made the circumstance necessary. My wife asked him, “What about robbing or murdering?” He said that even in those cases, it wasn’t really “wrong” because the offender was supposed to do it. I decided to jump right to the most extreme example to test his idea. “So if a woman gets raped, the rapist didn’t commit a sin?” He shrugged and said, “Well, no. I guess there’s something he needed to learn from it.” As shockingly false as the whole idea was, I had to concede one thing—at least he was consistent. He followed his doctrines to their inevitable end.

6. Incomplete Theodicy

The second error related to spiritual death’s necessity has to do with theodicy, or the problem of reconciling the idea of a good God with the presence of evil and pain in the world. While the previous error holds that sin is necessary, this error holds that pain and suffering are unnecessary.

One of the most profound doctrines that was restored in the latter days is the truth that sorrow and joy are two sides of the same coin. Lehi’s speech to his son Jacob is probably the most extensive scriptural discussion of this principle. He says in part:

11It must needs be, that there is an opposition in all things. If not so, … righteousness could not be brought to pass, neither wickedness, … neither good nor bad, … happiness nor misery. …

22If Adam had not transgressed, … 23they would have remained in a state of innocence, having no joy, for they knew no misery; doing no good, for they knew no sin. (2 Ne. 2:11, 22–23)

Thus Lehi explains that one cannot have the capacity for joy without also having the capacity for misery. While this can be a difficult doctrine to understand or accept at certain times in life, I have personally come to know that it is profoundly, vitally true. Joy is made possible by sorrow. Space does not permit a fuller discussion of how that is true (I don’t know that a whole library of books could satisfactorily “explain” it); all I can offer here is an analogy that came to my mind in high school that for some reason helped me understand it better.

Rather than thinking of joy and sorrow as paired opposites, like black and white tokens that we have to collect equal quantities of, I think of them as intrinsic opposites—two ends of the same stick. To put it another way, think of joy as refreshing water to drink, or some other favorite juice or beverage. Sorrow is not a sour-tasting drink that we have to swallow between each sip of water; sorrow is the digging process that widens and deepens that hole in which we store our water. Sorrow is the cistern; joy is the water. Sorrow increases our capacity to experience greater joy.

This truth, however, is tied to a certain Restoration interpretation of the Fall of Adam and Eve. We can only understand it by embracing the fact that Adam and Eve needed to Fall in order to bring these spiritual opposites into this world. This is not the interpretation of the rest of Christianity, however.

If you ask a traditional Christian why God created a world with pain and evil, they will often say, “He didn’t; he created it free of evil and pain, and humans messed it up, against God’s intentions.” They are right about the world being originally pain free, and being changed by human choice. But they are wrong about God’s intentions. Their reasoning usually goes like this: “All evil and pain is ultimately caused by human sins. God originally intended a world with no suffering or misery; He would have a universe free from any kind of pain or sorrow. The only reason we ever experience pain or sorrow is because we do something against his will, since he would never want or ask us to experience anything unpleasant. If mankind were to fully cooperate with His will, there would never be any need to experience unpleasantries. Absent the Fall, the cosmos should have been such a place, and God intends to eventually make it that way again.” To see an example of this argument being used to answer the problem of evil, see this clip of a debate between two Christians, Ray Comfort and Kirk Cameron, and two atheists, Brian Sapient and Kelly (skip ahead to minutes 8:15-10:45).

In my limited experience, it appears that this idea is fairly common among creedal Christians (meaning traditional Christians, who accept the creeds developed after the Church fell into apostasy). They believe that sorrow is not necessary, and any sorrow that does occur is always the result of sin. Over the last two years, my wife and I have had the blessing of participating in interfaith dialogues, wherein we chat for a few hours with evangelical Christians about each other’s beliefs (they’re very fun visits, and we’ve made some great friends). I have made a habit of including one particular question at some point in each dialogue: “Do you believe pain and suffering—not the kind that come from sin, but the kind that result from being mortal and subject to disease, death, and inconvenience—is necessary? Do we need to experience suffering in order to experience joy?” I’ve asked the question on different occasions in four different groups, and each time the answer was, “No.”9 My conversational partners will usually add that suffering is inevitable in this fallen world, and that it can be useful to instructing us and developing Godly attributes. But ultimately, no, it is not necessary. Sorrow did not have to be part of the equation. Sorrow is not necessary for joy to exist, and God intended a universe where we only experienced the latter.

I believe that traditional Christians’ interpretation of the Fall cuts them off from a full understanding of the necessity of suffering. As long as we believe that sorrow is unnecessary and is only caused by sin, we can never recognize the profound doctrine that sorrow is the flipside of joy, and is thus necessary for any kind of meaningful existence.10

I don’t mean to be blasé about suffering. There is a world of difference between understanding this doctrine in theory and actually turning our suffering over to the Savior, allowing him to redeem it and transform it into something meaningful and good. That’s a very personal process that lasts a lifetime. I wouldn’t be so emphatic about its importance if I hadn’t experienced part of the process myself. I certainly hope I haven’t made anyone feel like their suffering has been minimized by talking about this doctrine. On the contrary, I feel so passionate about this doctrine because it does give our suffering meaning.

And for that reason, I am saddened that the traditional Christian interpretation of the Fall effectively cuts off many people from fully understanding and embracing this important truth. I think that an oversimplified view of spiritual death exacerbates the problem of evil, and that the Book of Mormon’s distinction between two kinds of spiritual death is a powerful key to eventually reconciling God’s goodness with the existence of evil and pain.

Conclusion

Once again, I’m not asserting that an incomplete doctrine of spiritual death is the specific cause of each of these false doctrines, but I do think they’re related. I think it’s easier to believe false ideas like these when one lacks a thorough understanding of spiritual death. And I believe that the Book of Mormon’s teaching that there are two kinds of separation is the key to unraveling a lot of confusion in the world.

Notes

1. Some explanations that seem wrong could be construed to be correct, if you allow for you a shift in meaning of terms part way through the quote. For an example, see the second quote on the quiz, from the Aaronic Priesthood manual. The statement could be considered accurate, strictly speaking, if we assume that when the author refers to the “presence of God,” they mean “temporal presence” in the second instance and “spiritual presence” in the third instance.

2. Joseph F. Smith, Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Joseph F. Smith, “Chapter 11: Jesus Christ Redeems the Repentant from Spiritual Death,†p. 95.

3. I seriously doubt she intended this, but the point still stands that if we’re not careful in our doctrinal expositions, our listeners can walk away with the wrong impression.

4. For one explanation of why this doctrine is so concerning, see Chris Heimerdinger, “The Re-emergence of a Flawed Doctrine,” FrostCave.blogspot.com, accessed 11 Apr. 2011. For a more nuanced discussion, see Casey Paul Griffiths, “Universalism and the Revelations of Joseph Smith,†in The Doctrine and Covenants, Revelations in Context: The 37th Annual Brigham Young University Sidney B. Sperry, ed. Andrew H. Hedges, J. Spencer Fluhman, and Alonzo L. Gaskill (Provo and Salt Lake City: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, and Deseret Book, 2008), p. 168–87.

5. S. Michael Houdmann, ed., “Where do I find the age of accountability in the Bible? What happens to babies and young children when they die?” GotQuestions.org, accessed 11 Apr. 2011.

6. Catechism of the Catholic Church 1250.

7. Interestingly, many non-LDS Christians intuit the truth that babies are innocent and undeserving of damnation. Many believe the scriptures “allow us to hope that there is a way of salvation for children who have died without Baptism†(Catechism of the Catholic Church 1261, Vatican.va). In order to reconcile this hope with many New Testament passages, they propose a distinction similar (in some ways) to the one the Book of Mormon makes between the two types of spiritual death:

To reconcile the truths that all humans are sinful but that children do possess a kind of “relative innocenceâ€, some theologians have suggested that the distinct variations in sin could carry different kinds of “death penalties.â€

For instance, could it be proposed that the penalty for inherited sin (sin passed genetically from generation to generation) is spiritual death (separation from God) which state, if left unchanged and confirmed in personal sin (sins personally committed as an act of free will) results in eternal death and eternal separation from God? Could the penalty of imputed sin (judicially passed from Adam directly to each individual—Rom. 5:12) be physical death?

If so, it could help us to understand how a child (born in sin, yet having not committed sin as an act of the will) could be subject to physical death without being subject to the penalty of eternal spiritual death. Infants, born “guilty†of both imputed sin (ultimately resulting in physical death) and inherited sin, would not be subject to the eternal penalties of sin until confirmed by personal acts of unrighteousness committed with an understanding of right and wrong. It must be confessed that the Scriptures do not explicitly teach the existence of these distinctions. (Scott S. Shepherd, “The Destiny of an Infant Who Dies (Prematurely)!?“ TheWordOut.net, accessed 25 Apr. 2010.)

The theologians mentioned propose two terms that (very roughly) correspond to the two types of spiritual death: imputed sin for the temporal separation, and inherited sin for the spiritual separation. There are still significant differences between the restored doctrine of spiritual death and this formulation, but the doctrinal outcome is the same—babies inherit spiritual death from Adam, but they do not necessarily go to hell if they die before accepting the Savior’s Atonement.

These theologians apparently consider the mental work of interpreting Bible passages regarding the effects of Adam’s fall to be worth the effort if it means finding the possibility that infants are not damned. Fortunately, such a possibility is boldly proclaimed as a reality in the restored gospel. While this good author forthrightly confesses that the Bible verses he examines “do not explicitly teach the existence of these distinctions,†the Book of Mormon does explicitly teach such a distinction. God be praised for the gift of modern revelation.

8. Robert Perry, “There is No Sin,” Circle of Atonement website, circleofa.org, accessed 11 Apr. 2011.

9. On one of the occasions (just a couple weeks ago, actually: Monday, April 18), I asked the professor who came with the students. He noted that some Christian theologians in history have argued that pain was necessary. For example, Irenaeus argued that we need sorrow and suffering in order to mature spiritually. But he clarified and confirmed that the vast majority of traditional Christians do not accept that position.

10. Another problem with the idea that all suffering is caused by sin is that it can never explain the suffering of innocents. If you really believe that all pain and suffering is caused by sin, what do you about the fact that every baby is mortal? Little children suffer from disease and sometimes die. These events are not caused by another human agent causing the problem—they are part of living in this world—so we can’t attribute it to someone else’s sins. If you really believe personal sin is the root of all suffering, then it’d be very easy to conclude that anyone who suffers must be sinful. In other words, if asked, “Why do innocents suffer?” the reply would be, “Because they’re not really innocent.”

Can you see how the Incomplete Theodicy concept is closely tied with the Original Sin and Infant Baptism concepts? These ideas are incorrect, but you can see how there is a kind of internal consistency in the way they are framed.

I really appreciate this post. It is at the core of my faith. Following are some questions for you.

Nathan: Traditional Christians [say], “All evil and pain is ultimately caused by human sins. Adam and Eve introduced suffering by partaking of the fruit, and each of us individually creates more suffering for ourselves when we personally sin. …”

When I read this, I thought, I believe this. It is the rest of the quote that I don’t believe. I would continue the quote in line with my thoughts as follows:

I really like your analogy of the water and the cistern. It gives that idea that the work to create the cistern and the hole or space we create in us is only so God can fill it with living waters.

Nathan: As long as we believe that sorrow is unnecessary and is only caused by sin …

Does not all sorrow come from sin? Either our own or those previous. Are you making a distinction between transgression and sin? There was no sorrow in the garden of Eden. Was it not Adam’s transgression that brought the earth to a fallen state where the pains of mortality and disease, etc., came to be? I agree that the fall was necessary. God knows we need it to develop fully. But it was Adam and Eve’s choice to transgress that brought it into reality on earth.

Nathan: If you really believe that all pain and suffering is caused by sin, what do you about the fact that every baby is mortal? Little children suffer from disease and sometimes die.

I would say that their suffering comes as a result of Adam’s transgression. And that Adam’s transgression was paid for by Jesus. Their suffering was temporary. They are still innocent and yet suffered the consequences of this world. Also, I would say that they chose to come into this life knowing that there would be pain and suffering.

Thanks for the terrific points you’re bringing up, Rich. I’m seeing places where I need to explain myself better.

Rich: When I read this, I thought, I believe this. It is the rest of the quote that I don’t believe.

I should have worded it more carefully. What would be your response if I were to change the first part of the second sentence to read, “Adam and Eve introduced suffering by

partaking of the fruitsinning against God’s will, and each of us …”?Rich: I would continue the quote in line with my thoughts as follows: “Yet this opposition is necessary. We must be put in a position where we can choose between good and evil.”

I agree with this. I would add, though, that such a position (where we can choose between good and evil) is not what I mean by sin. I think temptation is necessary, and that evil options are necessary, and that it’s necessary for the consequences to actually be applied when they’re chosen. But I don’t think it’s ever necessary for a person to go the extra step and actually sin—to act on the temptation and choose the evil option. Does that distinction makes sense? Would you agree with it?

I’m glad you liked the water/cistern analogy. It profoundly affected me when it first occurred to me.

Rich: Are you making a distinction between transgression and sin?

Yep, I’m making a distinction. I think perhaps the most simple and useful definition of sin is “doing something God doesn’t want you to do.” For that reason (among others), I don’t believe Adam and Eve sinned in just the act of eating the fruit, and I strongly suspect that’s why Joseph Smith decided to use a different term to describe their action. Were you making a distinction as well? Do you agree that Adam and Eve did not sin in eating the fruit?

Rich: Does not all sorrow come from sin? Either our own or those previous.

It seems to me the answer is no. Consider the first moments after Adam and Eve ate the fruit. The world was now mortal, but no one had sinned yet. People could die or get seriously injured, but we would not be able to say it was caused by sin, since no actual sin had occurred yet.

I think this scenario is important to consider, because it illustrates the difference between sorrow caused by necessary trials and misery caused by unnecessary sins. I’d planned to discuss this in my next post, but I’ll just add that I think this is the message of the book of Job—that some sorrow is not related to sin at all. In a mortal world where no one had sinned yet, a toddler could still stumble and fall over a cliff and die. That would cause a lot of sorrow, but there would be no previous sin that we could attribute it to.

Rich: I agree that the fall was necessary. God knows we need it to develop fully. But it was Adam and Eve’s choice to transgress that brought it into reality on earth.

I agree the Fall was necessary, and that Adam and Eve’s transgression caused it. I think it’s important to know that eating the fruit was not a sin, because if we thought it was a sin, then we’d be saying that sin was necessary, since they had to sin in order for the Fall to happen. If you’re distinguishing between sin and transgression with regard to the Fall, how would you define the difference?

==========

Note: I have changed some wording in the article to (hopefully) clarify the things Rich brings up.

This is very useful. I think that your insight that these doctrinal errors result from zig-zagging between the two types of spiritual death is particularly helpful and is a significant upshot to your theory, which has great explanatory potential for resolving these problems.

I am still struggling with resolving the problems associated with what you call theistic amorality, specifically issues related to the necessity of the fall. In my study of the matter it seems to me that one of the major purposes of the fall is that it was the only way that Adam and Eve could have knowledge of good and evil. This is because such knowledge is not propositional (it cannot be learned from studying facts) but instead it is affective and practical knowledge, learned through first-hand personal experience and action.

If this is the case, then it seems that similar experience is required for each of us to truly understand good and evil. I’m talking about some sort of individual fall, not necessarily a major transgression, but some experience in which we disobey God and can, therefore, understand evil first hand.

One potential solution to the dilemma that I am toying with is the possibility that this knowledge could be obtained by experiencing evil as it is enacted upon us rather than enacted by us. I’m still not sure if this will work but it may be the only way to allow for innocent children to progress.

SGarff: The fall … was the only way that Adam and Eve could have knowledge of good and evil. This is because such knowledge is not propositional … but instead it is … learned through first-hand personal experience and action.

I agree with this, with regard to knowledge of certain kinds of experience: physical pain, death, disease, disappointed goals or aspirations, delayed gratification, being obliged to share limited resources, having to prioritize your duties because there is a limited amount of time in which to accomplish them, etc. All of these are experiences that our sinless Savior could have and probably did experience during his mortal life.

SGarff: It seems that similar experience is required … in which we disobey God and can, therefore, understand evil first hand.

I think we have to be really careful about extending the set of experiences I listed above to include things like rebellion against God’s will, selfishness, or pride. For one thing, it puts Heavenly Father in the awkward position of telling us not to do something, then winking at us and thinking, “If he’s really in tune with my purposes, he’ll do the opposite.” 🙂 For another thing, it leaves the question of how Jesus Christ—who was both sinless and our exemplar and far ahead of us in spiritual development—managed to progress so far beyond us without ever disobeying God. We would have to conclude that we are privy to certain knowledge and Godly attributes that Jesus Christ just doesn’t have access to because he never sinned. (For an article discussing this, see “I am the Way … Unless You Find a Better One”.)

SGarff: [Perhaps] this knowledge could be obtained by experiencing evil as it is enacted upon us rather than enacted by us. I’m still not sure if this will work.

I’ve considered that possibility as well—that perhaps another kind of knowledge that must be personally experienced is, not sinning, but being the victim of other’s sins. However, I balk at embracing it because it still requires that somebody sin in order for me (or, say, an innocent child) to progress. If such were the case, then the person who sinned and was condemned would be the ultimate Savior, because he gave up his salvation in order to help others move forward (see, for example, this quote). That’s a really unpalatable plan of salvation, to me at least. I can’t see how a good and just Heavenly Father would create a plan that hinged on the need for someone to sin. (That may raise the question of “But isn’t Satan necessary?” See this comment for one possible solution to that matter.) It seems to me that the kind of knowledge that comes from committing sin is exactly the kind of knowledge that could come through other means, such as propositionally, or through the Holy Spirit. (For an article discussing this, see Knowing without Doing.)

SGarff: It may be the only way to allow for innocent children to progress.

If we assume that sin (either as a committer or a victim) isn’t necessary for anyone to progress, then it seems to me that there’s no problem with a person’s mortal probation ending before they reach the age of accountability.

Rich and SGarff, thanks for bringing these things up. It helps me to think more clearly, and to know whether I’m covering all my bases as I reason out loud in these articles. Please continue to let me know your thoughts and your reactions to mine.

Interesting quote about the necessity of the devil. I tend to agree that the devil is not actually necessary. In fact, I think he gets much more credit than is due. I like the Calvin and Hobbes exchange where Calvin asks Hobbes if there is a devil constantly tempting man to act badly. Hobbes replies, “I don’t think man needs the help.” I think most sin is better explained through our agency rather than some unseen, unexperienced tempter. I think we would have to be consciously aware of Satan’s influence, otherwise our agency is undermined.

Good point about the Saviour being able gain this knowledge without ever transgressing the laws of His Father. Though I wonder if perhaps His is a special case because the atonement would allow him to experience sin and its consequences first-hand for each one of our Father’s children. Of course, it is also plausible that Christ needed knowledge of good and evil long before this point (I wonder how Satan’s temptations at the beginning of Christ’s ministry fit into this).

The difficulty as I see it stems from the following argument:

I tend to agree with 1 and 2, but I am uncomfortable with 3. It is possible that the way the fall is relevant is not that it is necessary for to go through this process, but that, in fact, we all have gone through this process because we all have sinned (not necessity but contingency that applies to everyone with exception of the Savior).

I wonder if you have seen this Mormon Review on Goethe’s Faust by Terryl Givens (http://timesandseasons.org/index.php/2009/09/mr-the-redemption-of-eve-joseph-smith-and-goethes-faust/). I think his points are interesting and well thought out, though I am not sure how he can avoid the problems of 3 discussed above.

One more wrinkle to further complicate this: It seems that not all evil is sin in the broadest view of the term “evil.” For example natural disasters can cause great suffering and may be experienced as “evil” by those subjected to them. It seems that there is a natural evil that is not the result of agency, but of the conditions of earth life (post-Fall, at least).

I completely agree with #1. I’m not quite sure what you mean by #2, particularly by the Second Article of Faith. Do you mean, the simplest way to apply it, without using the incorrect interpretation of original sin? As I reread it, I’m guessing that’s what you mean, and yes, we want to avoid that interpretation. However, I’m not sure you’ve summarized the Fall in a way that takes full advantage of restored doctrines. For example, you said,

SGarff: Replacing ourselves for Adam and Eve. We each have our own personal fall in which we disobey our Creator …

Several modern prophets have emphasized that Adam and Eve didn’t disobey their Creator, per se. This seems to be one of the most crucial changes in understanding that is needed to understand the Fall:

Since Adam and Eve weren’t disobeying God, it seems like the application of the story doesn’t need to involve disobeying God. I think perhaps a better (or at least alternate) way of applying the Fall story is not to symbolize our descent into personal sin and the spiritual separation, but our descent into mortality and the temporal separation. That is, just like Adam and Eve, we each began our existence in a paradise in God’s presence (the premortal life). The Lord presented two choices: stay with him, or voluntarily leave his presence and enter a mortal world of pain (our births into earth life). Doing so would help us “be as gods” by becoming more like Heavenly Father. As a result, we each gain knowledge of good and evil (reaching the age of accountability in late childhood).

This seems to me to offer an application that doesn’t imply that sin is necessary. In other words, I accept #1, and I offer an alternative to #2, which makes #3 no longer a necessary conclusion. What do you think? (Let me add, I don’t necessarily think that an application of a story should retroactively affect the meaning of the story itself, but I’m trying to work within the framework you gave.)

SGarff: It seems that not all evil is sin in the broadest view of the term “evil.†For example natural disasters. … It seems that there is a natural evil that is not the result of agency, but of the conditions of earth life.

I completely agree. This is the distinction I was trying to make at the beginning of my previous comment. The “evil” of natural disasters and conditions of earth life (pain, disease, limited time and resources) is the necessary kind of suffering that comes from Adam’s Fall, and does not involve sin. The “evil” of sin is the unnecessary kind of suffering that comes from rebelling against God’s will. That’s why I believe Adam’s Fall shouldn’t be used as evidence that sin is sometimes necessary.

One more point: I think discussions like this one are best served if everyone is clear on the definitions they are using for sin and transgression. What definitions are you using?

Also, I have not read Terryl Givens’s piece, but I’m very curious now and will probably print it out and read it soon. I’m really hoping he doesn’t try to show sin as a necessity, because, like you, I find that idea very uncomfortable. I don’t think it jibes at all with the teachings of prophets.

I know I wrote another comment. I won’t take the time to re-write it completely right now. The gist of it was that I had been using the word sin when I should have used transgression.

I believe that all suffering comes from our own and others transgression and sin.

It is still in moderation. I see that now.

SGarff: It seems that not all evil is sin in the broadest view of the term “evil.†For example natural disasters can cause great suffering and may be experienced as “evil†by those subjected to them. It seems that there is a natural evil that is not the result of agency, but of the conditions of earth life (post-Fall, at least).

I would argue that these things are not “evil.” Anything that results in pain and suffering has been classified by our modern society as an evil, but I don’t think that is necessarily the case. I don’t think pain, suffering, and sorrow are inherently evil. I believe what Viktor Frankl said: “Human life can be fulfilled not only in creating and enjoying, but also in suffering.”

For this reason, I don’t classify natural disasters, illness, or suffering that is not the result of sin as evil. We came to this earth to experience these things, because these are things that help sanctify us and prepare us for Godhood.

There is a longstanding philosophical tradition known as hedonism. Not the naughty word that refers to gluttons and such, but rather the philosophical tradition that tells us that pain is an inherent evil to always be avoided. I propose that hedonism is at odds with the reality of Christian doctrine. Pain and suffering are not inherently bad, and we can make sense of our suffering in such a way that, even in the midst of our pain, we can call it a refining good.

To clarify, yes, we can experience these things as “evil.” But I don’t think they really are, and we can also (depending on how we make sense of it) experience them as refining, necessary, and perhaps even good.

Note: This comment was originally submitted earlier but got snatched by the auto filter. Sorry ’bout that, Rich.

Thank you for your response. I am learning to use words more accurately. The heart of my misunderstanding is the difference between the definitions of transgression and sin. I sometimes use the word sin when I mean transgression.

From my understanding, a sin is a kind of transgression. But a transgression is not necessarily a sin. The definition does not say that a transgression is breaking a commandment without knowledge or a mistake; it can be inferred from it. I have heard some use transgression as a way to refer to sin as well. I did notice in my search on lds.org that there were many to referred to them both.

I would restate my belief as “All evil and pain is ultimately caused by human transgression and/or sins. Adam and Eve introduced suffering by partaking of the fruit or transgressing against God. Each of us individually creates more suffering for ourselves when we personally transgress or sin.”

Would you agree that all sorrow comes from transgression or sin? Either our own or committed by those previous?

I agree that we do not need to sin to progress, that in fact sin (as opposed to transgression or innocent mistakes) does inhibit us from progression towards God. It may even stop us in our progression if we choose to not repent, to not turn towards God. I liked and agree with your series on The Path of Sin.

Rich: From my understanding, a sin is a kind of transgression. But a transgression is not necessarily a sin.

That’s my understanding as well.

Rich: I have heard some use transgression as a way to refer to sin as well. I did notice in my search on lds.org that there were many to referred to them both.

Yes, I’ve noticed that in many, perhaps most cases, they are used synonymously and interchangeably. I’ve got a few quotes that explain why. Like, one from Gerald Lund where he says that sometimes terms are used generally or interchangeably, but sometimes when a prophet is trying to explain a very nuanced, detailed doctrine, he will give words very specific meaning. Doing so is useful for the purposes of that prophet’s particular sermon, but we shouldn’t assume that that means every other sermon uses those same definitions.

So yes, many passages use sin and transgression to mean the same thing. In some talks, usually ones about the Fall of Adam or the innocence of children, the speaker will use more technical meanings. (The funny thing is, I was going to make my entire next post be on this very subject. Do you think that would be helpful?)

Rich: The definition does not say that a transgression is breaking a commandment without knowledge or a mistake; it can be inferred from it.

Some sermons will use that technical definition of transgression—usually when they’re explaining why little children are sinless, but we still see them do naughty things. Sermons about the Fall of Adam usually use a different technical definition, like Elder Oaks’s talk “The Great Plan of Happiness.”

Rich: Would you agree that all sorrow comes from transgression or sin? Either our own or committed by those previous?

I’d agree that all sorrow comes from transgression, depending on the definition of transgression. The one I like the most, I heard from Thomas Valletta, the Director of Curriculum at CES, and the editor of those great scripture editions “For Latter-day Saint Families.” He went to the root of the word, which means “move across” (like progression means “move forward” and digression means “move backward”). He said that if we think of Adam’s decision as “moving across” from one condition (paradisiacal, amortal Eden) to another (painful mortality), then it makes a lot of sense to call it a transgression, but not necessarily a sin. In that case, then yeah, I guess everyone who suffers the necessary pains and sorrows of mortality does so because they made the same freely chosen decision to come to this mortal earth.

Rich: I agree that we do not need to sin to progress, that in fact sin … does inhibit us from progression towards God. … I liked and agree with your series on The Path of Sin.

Glad to hear it. 🙂

Whichever definition of transgression a person wants to adopt, my main point is that it’s distinct from sin, and it’s not necessarily against God’s will. My main thrust is that, like Jeff says, pain and sorrow are not intrinsically evil, and they are not suffered by people only as a punishment for choices they made which were against God’s will. A perfectly good and righteous person could still suffer, and indeed needs to suffer in order to become like God.

If we don’t understand that truth, I think we are held back from fully understanding our own pain and sorrow. If we ascribe the source of all our afflictions to sins, whether our own, our neighbors’, or our first parents, then we aren’t learning and developing all the Godly lessons and attributes we should be.

I think this is why Enoch was so surprised to find out that God weeps (Moses 7:28–31). Perhaps Enoch had previously assumed the same idea that we find in Trinitarian creeds, that God is “without passions”—that since God is perfect and sinless, he would therefore never experience sorrow. But it turns out that sorrow is a very Godly attribute, because it is the flipside of joy; one cannot exist without the other.

Nathan:

Yes, I am making a distinction between transgression and sin. “Transgression†means to disobey or transgress a law, commandment, order, instruction etc., such as Adam and Eve did by partaking of the fruit when the Lord forbade it. The definition of “sin†is a little bit more complicated (I remember being at a total loss on my mission when we were teaching a Buddhist and she asked me what sin is). Think I will settle with this definition: Willfully acting in a way we know is wrong/evil.

A transgression is not necessarily a sin. For example, Adam and Eve’s transgression may not qualify as sin for two reasons. First, if the two commandments—don’t eat, and multiply—were contradictory as many LDS assume, then to choose the greater good, even if it is a technical transgression, would not be a sin, because there is no choosing of wrong. Second, the mens rea for sin, as defined above, must include a knowledge of good and evil coupled with a knowledge that our act falls on the evil side of the distinction (mens rea is a legal term for the requisite state of mind to be guilty of certain crimes, i.e., “with malice aforethoughtâ€).

Even if you accept 3, sin is not necessary, only transgression (for Adam and Eve and us), though I’m not sure if you can acquire the same knowledge of evil by mere transgression without actually enacting evil itself.

As is likely clear from my distinction above, I do think that Adam and Eve did technically disobey God, because God forbade partaking of the fruit. The phrase “thou mayest choose†could be a reminder of free will and responsibility, or it could be an indication that a technical transgression here would not be considered sin. I do not interpret God as saying that the He is not commanding them one way or the other. I just don’t see how one can get around the fact that God reminded Adam and Eve that He forbids partaking of the fruit.

Interesting point about the fall relating to our pre-existent choice to come to earth. Something seems very aesthetically right about that and I’m sure there is some relation. I think there needs to be more, though. Adam and Eve (presumably) made this same choice to leave God’s presence before coming to the garden, but nevertheless were still required to enact the fall to actually leave God’s presence once on earth. This makes me suspect that we also enact the fall on earth. This also follows from the fact that we are born 100% pure and innocent with no spiritual separation from God.

Jeffrey:

While I reject philosophical hedonism, I do believe that there is some natural suffering that can only be classified as evil, at least by those it is inflicted upon. Certainly suffering is requisite for our earth experience and can help us progress. However, I fail to see the positive effect of child starvation and people being burned to death. I reject Nietzsche’s old saw that “whatever doesn’t kill you only makes you stronger.†I think that through the atonement all suffering can be converted by Christ into something good. However, by itself, some suffering is nevertheless evil.

Also experientially speaking, there is often no distinction between suffering caused by nature and suffering caused by sin. Starvation is experienced the same whether it is caused by greedy warlords or drought. A broken neck hurts the same whether it was caused by a falling tree or a drunk driver.

I think you are be right, we experience these things as evil even though they are not actually evil. I just think that is the experience that counts.

Rich: I would restate my belief as “All evil and pain is ultimately caused by human transgression and/or sins. … Would you agree that all sorrow comes from transgression or sin? Either our own or committed by those previous?

and SGarff: Even if you accept 3, sin is not necessary, only transgression (for Adam and Eve and us).

I don’t understand why it would be necessary to say that. Why couldn’t there be pain in a transgressionless, Zion society? Imagine a community of perfectly obedient, sinless people in a mortal earth. No one is cruel or selfish or even inconsiderate. There is not only no willful sin, but no one is ignorant of the law and everyone keeps all the commandments. Why couldn’t there still be pain and sorrow? Why couldn’t there still be sickness, or fatal accidents, or miscommunications that lead to inconvenience and problems? If we really need to experience suffering in order to become like God, why does that suffering require that someone first break one of God’s commandments, even in ignorance?

SGarff, I think your definition of sin is a good one. I also agree with your two possible reasons why Adam and Eve’s choice wasn’t a sin, especially the first one. This is why, if we say Adam transgressed, I think we should not define transgression as “Disobeying God’s will,†but it’s OK to define it as “Disobeying a commandment or law.†For those to whom that seems like a weird distinction, let me explain. I think it’s the same point SGarff is making:

SGarff: If the two commandments … were contradictory as many LDS assume, then to choose the greater good, even if it is a technical transgression, would not be a sin, because there is no choosing of wrong.

Put another way, if God articulates two commandments that seem directly contradictory, it seems to me we can assume that at least one of them has implicit qualifiers like “unless a more important/urgent commandment must be kept.†Four examples come to mind: Adam and Eve eating the fruit, David eating the shewbread (Matt. 12:4; 1 Sam. 21:6; Lev. 24:9), Nephi killing Laban (and deceiving Zoram and stealing the plates), and bus drivers bringing people to church on Sunday. In all four cases (Eve, David, Nephi, driver), the person technically transgresses a lower law in order to keep a higher law. I’d say that in all four cases, they did the right, good thing; they did God’s will. To put it in an odd and unconventional, yet consistent, manner: sometimes God desires us to transgress. (Would you guys agree with that?)

However, if we define transgression as “Disobeying God’s will,†then saying Adam and Eve transgressed is like saying that God didn’t want Adam and Eve to eat the fruit. But several modern prophets have clarified that he did want them to, just as he wanted Nephi to transgress the law against killing, and David to transgress the law against eating shewbread. So if we define transgression as “Disobeying one of God’s laws or commandments,†with the understanding that sometimes transgressing is a good and necessary thing that God wants us to do, then there’s room for the idea that sorrow is necessary.

I guess I think it’s important to define transgression in such a way that they are not unwittingly implying that Adam and Eve shouldn’t have eaten the fruit, because it seems pretty clear from modern prophets that they should have.

SGarff: I’m not sure if you can acquire the same knowledge of evil by mere transgression without actually enacting evil itself.

I’m not sure what you mean. Doesn’t that lead back to the same problem: How did Jesus acquire such good attributes and wisdom if he never sinned (if that’s what you mean by “enacting evilâ€)?

SGarff: I do believe that there is some natural suffering that can only be classified as evil, at least by those it is inflicted upon. … I fail to see the positive effect of child starvation and people being burned to death.

What if the child starved because he got lost in the desert, as a faultless accident, or the people were burned to death because lightning started a forest fire? Would that suffering be intrinsically evil? I ask because you said they can only be classified as evil, but then you said,

We experience these things as evil even though they are not actually evil.

I’m not really trying to make a point with this question, just trying to understand what you said.

My two cents:

Greedy warlords are evil. Driving drunk is evil. Starvation and injured necks just are.

I would say that thoughts, deeds, intentions, etc. can be classified as evil (they are actions caused by a moral agent), but I wouldn’t classify consequences, punishments, etc. as evil (they are the effect or result of an action or occurance).

When Adam and Eve were cast out of the garden, did God perpetrate some evil upon them? Nah.

Nathan: What if the child starved because he got lost in the desert, as a faultless accident, or the people were burned to death because lightning started a forest fire? Would that suffering be intrinsically evil? I ask because you said they can only be classified as evil, but then you said, “We experience these things as evil even though they are not actually evil.”

Yeah I didn’t make that very clear. My point is that, though I agree that natural disasters and such are technically not evil, the distinction may be unimportant to those who suffer great loss/pain from natural causes. I agree that to actually be evil there must be some evil intent, thus disqualifying natural disasters, but it is cold comfort to the victims and it would be hard to persuade them that a natural disaster wasn’t evil. In some instances, it is the experience that counts (BTW I’m not trying to get into theodicy here). My point was more about sensitivity and understanding than it was about rigorous philosophy.

Nathan:How did Jesus acquire such good attributes and wisdom if he never sinned (if that’s what you mean by “enacting evilâ€)?

Again, I think that the Savior may be a special case as He personally experienced all of this through the atonement and could, therefore, obtain an affective knowledge of evil without actually enacting it.

Thanks, Matthew. Thanks for the two clarifications, SGarff. I see better now where you’re coming from.

SGarff: It is cold comfort to the victims. … My point was more about sensitivity and understanding than it was about rigorous philosophy.

Yeah, that’s the hard thing about addressing theodicy. The question of evil doesn’t arise in a vacuum. Every time I write an article on the topic, I’m constantly aware that each phrase could potentially hurt someone’s feelings if I’m not careful. I’m motivated by the thought that the restored gospel has unique insights that can help us through our grief, but I’m never sure that I’m equal to the task of articulating how. Thanks for being patient.

SGarff: The Savior may be a special case as He personally experienced all of this through the atonement and could, therefore, obtain an affective knowledge of evil without actually enacting it.

I think that’s an important insight—that there are situations where the Spirit can give “experiential” knowledge outside of enactment. Have you read the Philip C. Smith quote about that in the post Knowing without Doing“? Do you think it’s possible that a person other than the Savior might be able to experience those “Gethsemane insights,” as a way to come closer to God without sinning?

Also, if I haven’t already bored you to tears by dragging on a conversation that you’re losing interest in (sorry <:-) ), do you have a moment to answer the question I asked earlier? (It probably got lost in the long comments.) Both you and Rich mentioned the idea of all pain and sorrow being caused by at least transgression, if not sin. I didn't understand why that would be necessary to explain sorrow or suffering. That is, if we really need to experience suffering in order to become like God, why does that suffering require that someone first break one of God’s commandments, even in ignorance? (See the original question here.)

Don’t worry. You’re not boring me. I love the great conversations I find on this site. The Philip C. Smith quote is interesting. Thanks for pointing it out. I like the notion that empathy allows us to know without doing. Certainly, empathy played a large role in the atonement. I still think that there is some knowledge that can only be gained through first-hand experience, riding a bike or swimming for example. I’m not sure that transgression fits into this category but it seems like it should, as it is a compelling explanation of the fall.

If I conveyed that all sorrow and suffering is caused by transgression, then I did not mean to. What I do mean is that some transgression was required as part of the fall in order for Adam and Eve and us to know good and evil.

OK, I understand now. And I agree that, while the Spirit can convey certain knowledge, that there are some things that must be actually experienced to know (and riding a bike and swimming are probably good examples). In fact, it seems to me that it’s that very fact that made it necessary for us to leave heaven and come to earth for this mortal probation—because our development was limited in certain ways as long as we hadn’t had those mortal experiences.

I just found this blog today. I’ll be returning when I have more time; great questions followed up by excellent thoughts. I’ve enjoyed being here.

So here is my 2 cents, (devalued for inflation), on whether we have to sin or not in order to accomplish God’s purposes in our life: I think it’s fascinating to consider, but in the end it doesn’t matter because He knew we would all sin. That doesn’t mean we HAD to sin, just that He knew we WOULD. For example, when my father gave me the keys to the car, he knew I would drive too fast. He didn’t make me do it, in fact he counseled me not to, but he also knew me well enough to know what I would do. (I’ve gotten better). This mortal plan works just as it was designed because he knew that all of us who reach the age of accountability would sin, and consequently have the opportunity to learn about grace and mercy and repentance, and etc. There were apparently many spirits who didn’t need to learn, first hand, about those things by sinning, so they were sent here in bodies that would give them other experiences but wouldn’t give them the experience of sinning (those with disabilities that keep them from being accountable, or those who die before the age of accountability). The rest of us will have ample opportunity to learn from sinning! (Well, at least I know that is true of myself, and everyone close to me…).

So whether or not sin is NECESSARY to accomplish the purposes of earth life, it has been the case that we provide plenty of sins to learn from anyway. I personally don’t believe our perfect father in heaven, who wants us to become like Him, requires us to sin in order to accomplish His work. But like my earthly father, He knew us well enough to know that we were going to sin anyway, and those sins would provide experience that could be used to change our natures, although we could also have our natures changed by other experiences.

I hope someone is still monitoring this thread because I’d like to hear if you think I’ve overlooked something essential in my reasoning.

I don’t think you’ve overlooked anything. Yours is a good pragmatic response—the immediate question is how to respond to the fact that we all have sinned. You’re right: the Lord does give us ways to learn from every sin if we apply the Atonement.

I’ll admit that the question of whether sin is necessary might seem more hypothetical and ethereal than the good point you make, but I think there is at least one pragmatic aspect of it. If we can answer it, then we can prevent the temptation to justify our sins or to be lax in our personal vigilance against committing sins. If we think that sin is necessary, then we open wider the door of temptation. So even in some practical ways, the answer to this question does matter, at least in my mind.

And by the way, we’re always monitoring the discussion on every post. No post is “dead” in our minds; we’re always ready for another round of thoughts on an old familiar article. 🙂 Thanks, Brian!

Thanks for the response. You make a valid point, and it involves the reason for my interest in the post to begin with: it is truly useful to be able to separate the truth from the not-so-truth. Critical thinking has no better application than in defending truth and clearing out the things that lead to unhappy consequences.

I’m sure I’ll be back for more soon.

“The not-so-truth” is now officially my Favorite Phrase of the Week. I’ll attempt to use it three times before dinner. 🙂