- What is the difference between science fiction and fantasy?

- Science fiction is speculative fiction in a naturalistic world

- Fantasy is speculative fiction set in a non-naturalistic world

- Creating a taxonomy of speculative fiction

- How writers signal that a work is science fiction

- How to craft genuine science fantasy

- Concluding thoughts (for now)

- Aslan vs. Qslan: Do Latter-day Saints worship a benevolent alien?

Most viewers distinguish between science fiction and fantasy based on aesthetic alone — futuristic settings, spaceships, and high technology have been key indicators of science fiction. But with the growing genre of science fantasy — fantasy universes with the aesthetic of science fiction — aesthetics are an increasingly less reliable indicator of science fiction. Writers need ways to signal to readers and viewers that the story takes place in a naturalistic universe. We will briefly explore some of these “signposts.” Our exploration will be cursory and not in any way exhaustive. But first we will address the elephant in the room: is advanced technology indistinguishable from the magic of a fantasy universe?

Clarke’s Third Law

Science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke famously penned three “laws” for science fiction writers. The third of them reads: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” This idea is played with in multiple Star Trek episodes, but one is notable: a primitive alien race has witnessed members of the Enterprise crew use advanced technology, and has concluded that Captain Picard is a god. (Indeed, a corollary of Clarke’s third law reads, “Any sufficiently advanced extraterrestrial intelligence is indistinguishable from God.”) In this video clip, Picard explains Clarke’s third law to one of them. He argues that any advanced technology will resemble magic to less advanced cultures and civilizations.

Some interpret this to mean that the distinction between technology and magic dissolves once a fictional society is advanced enough. Indeed, this has often been used as a key part of the distinction between science fiction and fantasy. We argue that this isn’t true, and that many writers misunderstand Clarke’s third law. It was not merely a statement that advanced technology and magic can look similar, or that it ought to; it was a warning that readers might mistake the former for the latter, if care is not taken to differentiate. Consider: for all of the extremely advanced technology found in Clarke’s science fiction, there is never a moment where readers mistake it for magic. This is precisely because Clarke takes great care to differentiate, and his third law was a warning to other authors to do the same.

Let’s consider a practical example: Teleportation in Star Trek is (in many ways) functionally equivalent with “apparition” in the Harry Potter universe. Both allow people to move instantaneously from one location to another, and through barriers, with absolute ease. And yet few Star Trek fans think of the Enterprise’s transporter system as magic, and few Harry Potter fans consider “apparating” to be a technology. Why? What makes one technology and the other magic has less to do with the results (and what they look like), and more to do with the kind of rules they operate under. Technology in Star Trek operates through naturalistic rules, and magic in Harry Potter operates through non-naturalistic rules.

In other words, sufficiently advanced technology can be distinguished from magic. Technology produces extraordinary results in a naturalistic universe, and magic produces extraordinary results in a non-naturalistic universe. As Carrier explains, “Clarke’s Third Law (‘any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic’) is only, at best, an epistemological principle, not a metaphysical one. Metaphysically, magic and technology are very definitely always distinguishable.” It’s the signaling, not the outcome, that informs readers which is which. And that may have been Clarke’s point all along.

Tropes that signal science fiction

In other words, science fiction often deals with weird or bizarre phenomenon, or technology so powerful that — were it not for the author’s signals — readers and audiences might mistake it for magic. In order to ground fiction in a science fiction universe, you have to signal to readers and viewers that the extraordinary things they are reading/seeing are indeed reducible to universal laws that govern inert matter or energy. You signpost them as the product of technology and a deep understanding of the naturalistic laws of the universe. Outside of directly stating that a universe and its technological marvels are naturalistic, authors have many tools to do this. Here are some examples:

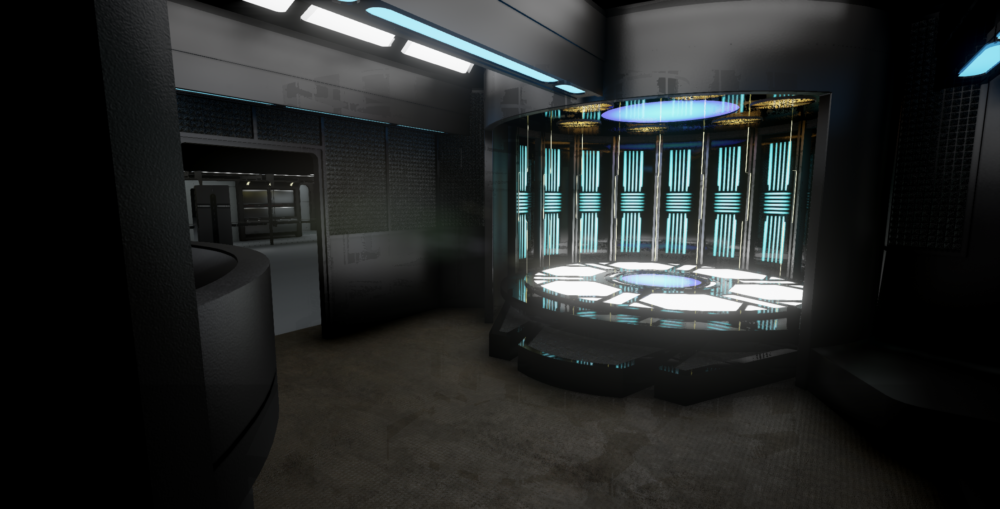

Have a machine nearby that does the work. Star Trek’s teleporters would easily be mistaken for magic were it not that the characters repeatedly go to a transporter room and stand on a transporter pad that is connected to a computer. They don’t seem to need the transporter pad in most cases — they do site-to-site transport all the time — but occasionally including the transporter pad signals to viewers that we are dealing with technology, not magic. In a fantasy universe, Carrier explains, “Words [can] directly cause what they request, without any mindless mechanism connecting the spoken word to the realized effect.” But a naturalistic universe needs extraordinary events to be reducible to mindless mechanisms, and so including such mechanisms — in the form of a machine or device — can signal that a story takes place in a naturalistic universe.

Use established terminology. Many fantasy universes have magic that allows a character to peer into another’s mind. But the moment you use the word telepathy, you signal to your readers that you are in a naturalistic universe, not a fantasy universe. There’s no good reason for this except historical convention, but key-words like this serve as useful signals. “Teleportation” is a similar term. Perhaps others can put together a list of similar technical terms that — if for no other reason than historical convention — help situate the extraordinary events of science fiction in a naturalistic universe.

Characters adopt a skeptical outlook. One way to signal that a universe is naturalistic is to have the characters who inhabit it assume that anything extraordinary they encounter can be reduced to naturalistic processes. After all, these characters have far more experience in their fictional universe than we do, and so if they believe their universe is naturalistic, it probably is — unless non-naturalistic events are so rare that characters rarely experience them. For example, the crew of the Enterprise never believe that something is magical; they always assume a naturalistic explanation for a seemingly supernatural phenomenon. One common theme of Star Trek is that they seek out the naturalistic explanations for any weirdness they encounter.

These sorts of tropes usually do not inherently signal that an extraordinary effect is naturalistic. There’s nothing about supernatural magic that says that a contraption or machine, for example, can’t be useful, or that characters in a fantasy story can’t also adopt skeptical attitudes or presume naturalism. However, these sorts of tropes often go a long way towards signposting in part because of already established, internal conventions of the in-story universe — that is, the existing “inertia” of the story. For example, it would take extraordinary signals to contraindicate the default assumption that the Star Trek universe is naturalistic. You would have to end an episode, perhaps, with an explicit conversation between Picard and Riker musing that maybe the supernatural is real after all.

In other words, the weight of prior worldbuilding helps give the above tropes some teeth. And this is true even when the story clearly contains non-naturalistic elements. Orson Scott Card’s Xenocide contains clearly non-naturalistic story elements, and so we would classify it as metaphysical fiction or science fantasy, rather than science fiction. But most readers assume it is science fiction, in large part because of the inertia of the broader book series to that point. In fact, the book itself included a story about debunking the supernaturalistic beliefs of those on the World of Path, and reducing extraordinary effects to naturalistic causes. This “inertia” leads people to ignore the non-naturalistic elements, or to simply assume them to be naturalistic, even when they clearly aren’t.

Examples of signposting extraordinary premises

These tropes illustrate the broader distinction: you can do bizarre, unusual, or extraordinary things in a science fiction universe; you just need to signpost to readers in some way that the universe is naturalistic. Here’s a few additional, quick examples:

- You can have telepathic characters, but you might signal that the telepathy works through naturalistic principles, by mentioning them as a genetic adaptation, or noting differences in the brains of telepaths, or mentioning brain waves or electromagnetic signals that mediate the telepathy.

- Vernor Vinge included “Zones of Thought” in several of his novels, including A Fire Upon the Deep, A Deepness in the Sky, and Children of the Sky. This appears to violate the basic principle of naturalism, which is that the rules of naturalism are universal. But science fiction can include rules that change across space, as long as we assume that there are deeper, more fundamental rules that explain the differences. In Vinge’s novels, we assume that the variation in rules has something to do with proximity to the gravitational center of the galaxy; further, we see evidence that advanced technology — that works on more basic principles — can change the contours of the zones.

- Star Trek includes godlike beings called Q, who seem to have the power to alter reality around them at will. This is the type of thing you might expect in a fantasy universe, but Star Trek so thoroughly establishes the universe as naturalistic that viewers assume the Q must operate on naturalistic principles. Science fiction can do godlike beings by positioning them as more advanced technologically or evolutionarily. Writers can signal this by implying that the super-advanced beings weren’t always that way; that they learned and developed into their present state. Certainly, super-powerful beings in a fantasy universe could have also learned and developed into their state; but a science fiction universe hints that this development was based on the discovery of fundamentally naturalistic rules.

There are myriads more examples. Again, the central point is that science fiction takes place in a naturalistic universe, which means that it takes place in a universe composed of inert matter governed by rules that are universal, unchangeable, passive, impartial, and morally neutral. Science fiction universes often deal with extraordinary phenomena that appear to violate these basic principles; but what makes it science fiction instead of fantasy is that it hints that the violated principles are, despite appearances, preserved.

Indeed, more than simply hinting, it seems that some stories in science fiction exist specifically to highlight this. There are a number of Star Trek episodes that start with an apparently supernatural premise — say, the appearance of the Devil, for example — only to then have the characters discover why the extraordinary phenomenon is really naturalistic. The story as it unfolds seems to have no deeper purpose than to present an apparently supernatural phenomena, and then debunk it; they demonstrate to viewers (or remind them) that naturalistic things need not appear naturalistic when we first encounter them.