Nathan Richardson

|

| Down syndrome does not cause a learning disability. If you don’t believe me, keep reading. |

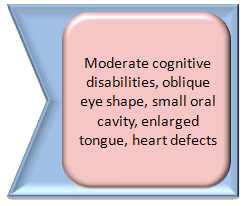

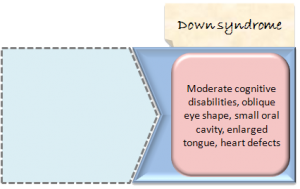

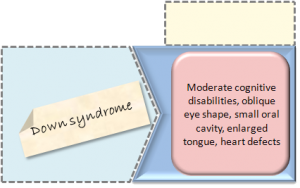

Once upon a time, there was a scientist who studied children and their biological and cognitive development. He met all kinds of children and became acquainted with a variety of personalities, body types, and abilities. Over the course of his travels and studies, he noticed one pattern in particular. He met several children who had similar characteristics: they had learning difficulties, accompanied by some unique facial features (slanted, Asian-looking eyes and enlarged tongue) and medical problems later in life (heart defects, thyroid complications).1 He wrote down the pattern of characteristics he was noticing:

The scientist was fond of these children and wanted to help make their lives better, perhaps by identifying and addressing the condition earlier in life or by preventing it altogether in the future with other children. He assumed that because there was such a high degree of similar characteristics among this group of people, the phenomenon might be an effect of some unknown cause:

He was very curious about what it was that caused this phenomenon:

Resolving a widespread and little-understood condition is a big task, and as with many scientific pursuits, it was not to be accomplished by just one person or within just one lifetime. So the scientist discussed it with other scholars far and wide. In talking about the condition, he found it useful (as do most scholars) to give that collection of characteristics a label. After all, it’s inefficient to invite people to an Annual Conference on The-phenomenon-of-having-learning-difficulties-accompanied-by-unique-facial-features-such-as-slanted-eyes-as-well-as-medical problems-such-as-heart-defects. So they labeled the phenomenon to save on ink cartridges:

Having a label made it easier to go about discussing and sharing information about their common pursuit. He and many other scientists then devoted hours and years of study to understanding and addressing the phenomenon. A large part of their study was aimed at discovering what caused the phenomenon. That was their main goal.

An Odd Turn of Events

Up to this point, this story is a true, if simplified, version of real events. However, imagine how silly it would seem if the following happened.

A man named, oh, Norman came along and asked the scientists what they were studying. They said, “Children with Down syndrome.”

Norman asked, “What’s Down syndrome?”

They told him, “It’s when a person has learning difficulties, slanted eyes, heart defects,” and described the other characteristics.

Norman nodded. “I see. So children who have those characteristics have Down syndrome?”

“Correct. We’re trying to understand why they have these characteristics.”

Norman replied, “Well, that’s simple. It’s because they have Down syndrome.”

The scientists blinked. “Well, what we mean is, we want to know what causes these characteristics.”

Norman shook his head patiently. “Down syndrome causes it, silly.”

Some scientists smiled politely while others just looked confused. Norman walked away shaking his head. “I don’t see why these scientists get so many research grants when their question has already been answered. We know perfectly well what causes those characteristics—Down syndrome does.”

The Nominal Fallacy

What Norman just did is commit a logical fallacy. This particular fallacy is called the nominal fallacy.2 (That’s why I called him Norman—because it kind of sounds like nominal. I know, gimmicky.) Norman observed a phenomenon, gave it a label, and then began to treat the label as though it were the cause:

The nominal fallacy is “the mistake of assuming that because we have given a name to something, therefore we have explained it.”2 In other words, talking as though the label were the cause.

To say that “Down syndrome” causes children to have the aforementioned list of medical conditions is about as accurate, insightful, and useful as saying that rain causes water droplets to fall from the sky. Rain does not make water fall from the sky; rain is water falling from the sky. What causes rain is another question entirely. Likewise, Down syndrome does not cause that list of conditions; Down syndrome is that list of conditions. What causes Down syndrome is another question.

Jeff Robinson, a psychologist, explains the nominal fallacy by giving another common example:

If I let go of this pen, what will happen? It will fall. Why? Gravity. People say gravity; the pen falls because of gravity. The fact of the matter is, we don’t know why the pen falls; all we know is that things that are unsupported fall. Gravity is one of the four fundamental physical forces of the universe that explain everything else, but nothing explains them. We just know that everything that is unsupported falls, and we call that fact gravity. We label the fact that things fall gravity. Now I like that: one of the things that influences our life the most is gravity—it influences me every single day of my life—and we don’t know why it happens. I think that’s wonderful, wonderful. We tend to think the world’s pretty explained. We label it and call it gravity, and then we do an interesting thing: we talk about it as though we have explained it. So why does the pen fall? Well, because of gravity. Well, how do you know there’s gravity? Well, because things fall. What makes them fall? Well, gravity.

Do you see it just goes in a circle? It doesn’t really add any information. We do that all the time in our society, in our culture: talk about things, label them, and then describe them as having acted as a result of the label.2

The first time I read this talk, I understood the fallacy Dr. Robinson describes but I completely disbelieved that gravity was a good example of it. I thought, “No, gravity is an entity, a force that causes things. Everyone knows that.” The fact that I misunderstood gravity shows how deeply ingrained the nominal fallacy can be in our view of the world.

Problems Caused by the Fallacy

Jeff discussed this fallacy in his article Gravity Made It Happen. Like him, I am not claiming that this is a widespread mistake made by scientists everywhere. I think, though, that many laymen make this mistake. And in some fields of study, it may be widespread.

The nominal fallacy might seem obvious and comical in the Down syndrome example; I intended it to be transparent like that, so as to be quickly grasped. But as I’ve learned about this fallacy, I’ve been surprised at how thoroughly entrenched it can sometimes be in the way we conceive of and talk about certain phenomena. I hope to elaborate in future articles, but some labels that I think many people sometimes mistakenly use as causative explanations include the following (readers are free to list other examples in the comments section):

|

|

There are at least two negative effects of making this mistake. First, it leads to a poor understanding of the phenomenon in question. This can, of course, lead to both mild and terrible outcomes, depending on what phenomenon we’re talking about. Second, it leads to complacency about pursuing a better understanding. If we think we already understand the cause of a phenomenon, then we stop studying it as we should; we don’t seek what we’ve already found.

The Right Approach

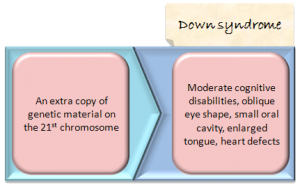

Using the story as an example, if the scientists in question had listened to Norman the Nomological Fallacist, they would have believed his schema and thought, “Well, we’ve solved the cause. All that’s left is to figure out how to deal with it when it happens.” In contrast, if they were to refuse to accept Norman’s complacency, recognizing the fallacy as an explanation that really explains nothing, they would continue their search, eventually discovering the cause of Down syndrome: an extra copy of genetic material on the twenty-first human chromosome, during conception. Having found the cause, they can now devote their efforts more effectively to preventing or managing the condition:

The purpose of this post was to clearly explain and illustrate the nominal fallacy, sometimes known as the nominalistic fallacy or the nomological fallacy. Why bother focusing on this particular fallacy on a site about the restored gospel? It is an incredibly frequent error that we often make, and it relates directly to many conversations about the gospel and living the commandments. In future articles, I plan to show how the nominal fallacy can actually lead us to deny certain core doctrines like agency. But even speaking generally, my hope is that by making explicit this logical error, we can all avoid making it in the future. Of course, if you find yourself making this mistake and someone calls you on it, just tell them that the nominal fallacy made you do it.

Notes

I apologize that some of the graphics are blurry. I can’t for the life of me figure out what setting I need to change to make them appear sharp. If anyone out there is a graphics wiz, please email me or let me know in the comments!

1. “Down Syndrome—Symptoms,” WebMD, accessed 2 Apr. 2010.

2. Jeffrey Robinson, “Homosexuality: What Works and What Doesn’t Work,” presentation given 6 Oct. 2002, TheGuardrail.com, accessed 13 Apr. 2010.

Would it still be a nominal fallacy if Norman said that the child exhibited certain characteristics because he had Down’s Syndrome, but Norman understood Down syndrome to be the label given to the condition of having an extra copy of genetic material on the twenty-first human chromosome? In other words, if the label “Down syndrome” was given to the cause (not the characteristics), would it still be a nominal fallacy? Are we in nominal fallacy territory since we still haven’t explained how the extra genetic material got there? Do we need to go back even further to find the cause for the cause of the characteristics?

When I say that someone has a runny nose because they have the flu, in my mind I’m using “flu” to describe the condition of being infected by the influenza virus, not the symptoms displayed. Is that a nominal fallacy? I really don’t know. Is that far enough back, or do I need to describe how the virus was contracted or how it works?

If Norman says it’s raining, he means water is falling without knowing why (because he’s a bit slow). If a meteorologist says it’s raining, he means that the atmospheric conditions (temperature, water vapor content, relative humidity, etc.) are such that the water vapor has condensed into liquid water droplets that are heavy enough to fall, etc, etc. Norman might be committing a nominal fallacy, but what about the meteorologist? Where do we draw the line? Is it based on the intent and understanding behind a given term?

If the label “Down syndrome†was given to the cause (not the characteristics), would it still be a nominal fallacy?

I’d say no. Like you said, it’s based on the shared understanding of what is meant by the word. The extra copy of genetic material is actually called “trisomy 21,” but if a group of people were to call trisomy 21 “Down syndrome,” then it would not be fallacious to say “Down syndrome causes these characteristics.”

For that reason, it’s important that everyone share the same definition for the labels they use. It’s especially important when causes are still unknown. Before genes were understood and trisomy 21 was discovered, it wouldn’t have made sense to call the cause of the characteristics “Down syndrome,” because we would be labeling an empty box. To label a cause when we haven’t identified it yet … well, it just seems like pretending to have more information than we do.

Is that far enough back, or do I need to describe how the virus was contracted or how it works?

I don’t think the nominal fallacy is about understanding a chain of causes perfectly; it’s about having something concrete behind the labels we use.

Good questions.

It’s so nice to be here again! I love reading your thoughts.

I’m going to suggest that the nominal fallacy could be itself a nominal fallacy. It isn’t really a concrete object; rather it’s a label used to describe a situation or train of thought. It doesn’t tell us anything more about the real thing behind the label.

That being said, I think it is a useful thing to talk about. It creates all sorts of misunderstandings in daily speech and professional fields. I do think it’s unfair to claim that psychology is more guilty than other field of using the nominal fallacy. In my experience studying psychology at my university, I have been continually reminded that most of the things we are talking about are simply constructs. We have various ways to test for construct validity, that is, we can try to define the degree to which the label we use actually describes some real, measurable thing. But in the end, all we are doing is creating a mental construct of a phenomenon that we have observed.

In that way, everything can be considered a nominal fallacy. Life. How do you know you are alive? Colors. How do you know it’s green? Joy. How do you know that you are happy? Why? How do you know your why is correct? Sadness, depression, music, taste. This can get really messed up if we take the extreme existentialistic view. How do you know you have 5 fingers? I see and feel five fingers. How can you see and feel them? Because I have five fingers. How do you know you have five fingers? and so on. Common sense tells us that some descriptions of reality need to be accepted, whether or not the accurately portray the concrete reality we live in. In the view of many prominent psychologists, it’s not reality that matters, but an individual’s perception of reality.

Still, we have these problems you talk about that come from a thought process we describe as a nominal fallacy. Even if I can’t be 100% sure that something called the nominal fallacy exists, the fact that you’ve applied the label to a construct allows me to think about this phenomenon. May I propose that the fundamental flaw of the nominal fallacy is not so much in using labels to describe causes, but in our simplified questions regarding the phenomena we wish to understand.

These children have Down Syndrome.

How do you know they have Down Syndrome? (This is a reasonable question)

(Here’s a tricky answer because most people, especially lay people want a quick and simple answer) I would answer, “Initially we assumed the condition was Down Syndrome by observing key features known to occur primarily other children classified as having down syndrome. If we want further proof of this assumption we could do genetic testing to verify the presence of an extra chromosome.

Why do they have Down Syndrome? (This is a seriously flawed question if being asked of anyone other than God.)

The problem is we don’t know why. As humans we can never know the detail of why. We can research some of the mechanisms of why, but we will forever be clueless about the causes of the why. Asking why is like moving half the distance toward an object. You can keep doing it forever and never get there. I can’t think of a question to which I truly understand the why beyond, “God wanted it that way.”

If posing the question why has any value or benefit, we have to be content knowing that the answers we receive will still be “half-answers.” Frequently the first step toward the object (and I might add the largest objective distance) is to say “Something causes these characteristics, not that we have any idea what that something is.” This description of the phenomenon is essential to taking the next step, which, incidentally, may or may not be possible in mortality. Despite the limitations, I still believe that it is helpful to take the first step at answering why.

Like you said, the trick is to avoid thinking that by taking the first step, we have arrived at the destination.

A final example: This food has too much salt. How do you know that? It tastes salty. Why does it taste salty? It has too much salt. How do yo know that? Are any of those questions or answers pointless? Is it okay to say that I put too much salt in the soup based solely on the fact that it tastes salty (which is in fact nothing more than a description of the circumstances.) Is the person asking about why the food tastes salty asking for the infinite chain of events that led me to pour in more salt than someone else might have? Or is he looking for a description of the biological process of taste perception down to the chemical reactions taking place on a sub-cellular level? Even then where do those processes start? Why do chemicals act the way they do? What caused the chain of events leading through my childhood, which was shaped by my parents’ experience, and so on back to Adam that influence my behavior today? Is my friend really interested in knowing the why or is he just looking for the first, or possibly second, step in the “why” question?

I’m excited to hear how you tie this to the gospel.

I think what makes the nominal fallacy so widespread is that we like simple, 1:1 explanations. It is easy and convenient to get the minimal information needed and then to sit back and say, okay, I get it, a person like that has down syndrome and that this why they are the way they are. End of story.

I don’t see anything inherently wrong with this, other than laziness, but then again we can’t all dive deeply into every field we are interested.

However, I do see a big problem with assuming that because the explanation appears to be 1:1, that there is an equally correlated single solution. This is my pet peeve when it comes to the general patient perception of medicine. I’ve heard people knock science complaining that doctors can’t even fix these seemingly “simple” (in other words, well defined) health problems without having to introduce this whole list of possible side effects. Drug commercials seem to contribute to this increased lack of confidence in science/doctors. It is easy to view drug commercials for things like RLS and think, oh, now that they have defined what RLS is, why can’t they treat it with something that won’t potentially damage your heart or liver or whatever other organ is listed in the potential side effects parts of the commercial. But the truth is, our bodies are complex and highly interactive.

If only the world was perfectly linear. It might be a boring, inefficient world, but we could sit and make all the nominal fallacies we wanted without worrying about our assumptions.

That is a great point, Toria! I hadn’t thought of that implication. By oversimplifying the cause/antecedents, we have simplistic expectations of the solution. Maybe that’s part of the reason people expect to solve so many things with one simple pill. If it has one simple name, it must have one discrete cause, so we should be able to address it without taking any related factors into consideration. Great insight.

Hi Nathan,

according to http://wordpress.tv/2009/10/28/the-image-widget-for-wordpress-com/

fixing images should be easy:

it looks like the images being displayed here are different ones than those they point to

just replace what is currently in “Image URL” with the content of “Link URL”, clear “Height” and save changes.

Hopefully this’ll help

Nice article by the way.

Isn’t talk about “God” the ultimate nominal fallacy?

No.

“I don’t think the nominal fallacy is about understanding a chain of causes perfectly; it’s about having something concrete behind the labels we use.” —Nathan

So, pray tell, what is the “something concrete,” if anything, behind the label “God”?

A living, breathing person we call God.

Which “God”? The “God” of the ancient Babylonians, or the Egyptians, or the ancient Greeks, or Romans, or the “God” Judaism, Hinduism, Islam, the Hindus, the Native Americas. Or are you referring to the “three gods” of Christian theism/trinitarianism? Anything that “lives” will die. “God’s” die too. What empirical evidence do you have for believing in “a living, breathing person we call God?” I assume you mean the “evidence” of “faith.” And is such an (alleged) God actually “breathing”? I though the Christian myth says “God” is a Spirit. Do spirits “breathe”? Your position is absurd, ridiculous, laughable. What “need” do we have of “the God hypothesis”? Simply some bogus comfort or consolation in view of our mortality? Pathetic!

Roy, let me try to explain my answer to your original question. We obviously disagree on whether there is a God. However, proposing an incorrect cause is not the same as committing the nominal fallacy. Let me give an example. Three people notice a certain phenomenon: a kind of rock that’s shaped like animal dung, except it’s mineral, not biological matter. They see this phenomenon often enough that they give it a label: coprolites.

Each of the three people proposes a different cause to explain where these dung-shaped minerals come from. Danny says they are caused by a combination of dinosaur defecation and fossilization. Eric says they are caused by erosion, being shaped naturally by wind and water. Norman says they are caused by coprolites.

Both Eric and Norman are wrong about what causes the phenomenon, but only Norman has committed the nominal fallacy, because the “cause” that Norman proposed was simply the label for the phenomenon he was trying to explain. The cause that Eric proposed turns out to be an insufficient explanation for the phenomenon he was examining, but “erosion” is still a concrete concept, even if it’s the wrong explanation in this case.

Likewise, even if someone was proposing God as the cause of some phenomenon, and they turned out to be wrong, they would not be committing the nominal fallacy unless “God” was also the label for the phenomenon they were trying to explain. For example, Eric and Norman notice that the sun comes up above the horizon every morning.

Eric labels that phenomenon “sunrise,” then proposes that God makes the sun come up. He points at the sun coming up and says, “Look, sunrise is happening right now.” When asked what causes it, he says, “God causes it.” Even if his hypothesis is wrong, it’s not the nominal fallacy.

Norman labels that phenomenon “God” (instead of “sunrise”), then proposes that God makes the sun come up. He points at the sun coming up and says, “God is happening.” When asked what causes it, he says, “God causes it.” That would be the nominal fallacy. (It’s a silly example, but it illustrates the point.)

Oh, and out of curiosity, how’d you come across this article?

Roy, Nathan and I are Latter-day Saints (Mormon). We believe that God has a physical body, and is a living, breathing (but immortal) person, and that He is not just a spirit.

What empirical evidence do I have of His existence? Only my personal communications with Him. He’s talked to me. I’ve had personal experience of His existence. You may think I’m crazy or delusional. However, I’m going to trust my experience.

I might also add, we’re not Trinitarian; we don’t believe in the traditional creedal descriptions of the three-in-one Godhead.