Nathan Richardson

|

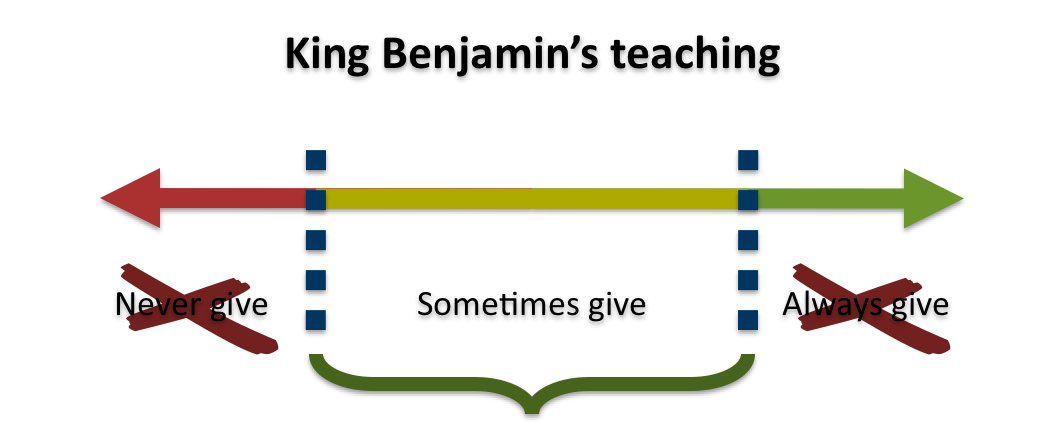

| King Benjamin actually did not say the Lord always requires us to give to beggars regardless of the circumstances. |

| Recap: Some Latter-day Saints read Benjamin’s sermon in Mosiah 4 and conclude that we must always give money to the poor when requested—even if it seems clear that they will misuse it and hurt themselves—because we are not supposed to judge people at all. I will call this the “Always give” view. |

Several possible rebuttals could be made against the “Always give” view. For one thing, there is the pragmatic argument. It would only take so many beggars before a person was drained of money and became a beggar herself.

Then there’s the logical argument. A person who holds to the “Always give” view must first define who qualifies as a beggar, but must do so without judging someone’s circumstances or motives. If you define it as “someone who has genuine need that they can’t provide themselves,” then the only way to identify those who qualify as a beggars is to make judgments about their needs and their abilities. If you define it as “someone who claims they have a genuine need that they can’t provide themselves,” then I could insist that you give me money. I really do need it. I promise. My family is in great need. If you draw attention to the fact that I’m employed, I could still insist that we are in dire need, with extenuating circumstances that you are unaware of, and make you feel guilty for judging my situation. (Of course, neither the pragmatic nor the logical argument invalidates the “Always give” view; they just make it a very difficult view to actually live.)

Then there’s the scriptural argument. Many passages of scripture can be found that clearly place conditions on helping the poor. For example, fourteen times in the following passage, Paul lists conditions for whether and how to give to the poor—conditions that clearly require some kind of judgment on our part.

3Honour widows that are widows indeed. 4But if any widow have children or nephews, let them learn first to shew piety at home, and to requite their parents: for that is good and acceptable before God. 5Now she that is a widow indeed, and desolate, trusteth in God, and continueth in supplications and prayers night and day. 6But she that liveth in pleasure is dead while she liveth. …

9Let not a widow be taken into the number under threescore years old, having been the wife of one man, 10Well reported of for good works; if she have brought up children, if she have lodged strangers, if she have washed the saints’ feet, if she have relieved the afflicted, if she have diligently followed every good work.

11But the younger widows refuse: … 16If any man or woman that believeth have widows [i.e., if the widows have family], let them relieve them, and let not the church be charged; that it may relieve them that are widows indeed. (1 Tim. 5:3–6, 9–11, 16)1

| If one prophet taught we must always give money to the poor, why would other prophets allow this sign to stand just outside the temple? |

Finally, there is the authority argument. Outside Temple Square in Salt Lake City, one block from the First Presidency’s offices, you can often see signs that say something like, “Visitors are encouraged to not give money to panhandlers.” If the prophet and president of the Church feels that, in at least some circumstances, it is appropriate to not give to a beggar, then I balk at the idea of implying he is at odds with King Benjamin.

The problem with solely making these kind of rebuttals, though, is that they either pit King Benjamin’s words against worldly reasoning (which is sometimes right, sometimes wrong) or against other prophets’ words. With the first possibility, of course the prophet wins out; sometimes we’re asked to follow prophets even when faced with apparently sensible reasons not to. But in this case, it’s an unnecessary tension. With the second possibility, we place ourselves in danger of pitting one prophet against another. Some might reflexively resolve it by citing Ezra Taft Benson’s true teaching, “Beware of those who would set up the dead prophets against the living prophets, for the living prophets always take precedence.”2 But this kind of trump card shouldn’t be played cavalierly, especially in the ambiguous territory of uncanonized, practical, timely instructions. I believe this response assumes a contradiction that isn’t really there; again, the tension is unnecessary in this case.

As in the vast majority of apparent disagreements between prophets or presidents of the Church, the resolution lies in examining their words more closely and realizing that they aren’t actually disagreeing. Such is the case with King Benjamin. I don’t believe he contradicts Paul, or any other prophet, at all. There are at least two reasons to conclude that King Benjamin is not teaching the “Always give” view, which is the view that we should always give money to a beggar when asked, regardless of his circumstances.

The Problems of Money

|

| Why does Benjamin say we should give our “substance,” rather than our money? |

One of the problems with the “Always give” view is the complications that arise with money. In a moneyless society, if you give a person a loaf of bread, you have provided her with the means to eat a loaf of bread. There’s really no negative outcome possible. In a … moneyful … society (what the heck is the opposite of moneyless? :-)), if you give a person $3.75, you have provided her with the means to eat a loaf of bread—or drink some juice, or ride on the bus, or get some cigarettes, or drink some alcohol, etc. There are several negative outcomes possible. Therefore, it’s conceivable that the giver now has to consider his partial accountability for what is done with his gift.

It’s interesting to note that King Benjamin never uses the word money, even though Nephites did have some form of money.3 Instead, he uses a different word when saying what we should give:

16Ye yourselves will succor those that stand in need of your succor; ye will administer of your substance unto him that standeth in need. … 17Perhaps thou shalt say: … I will stay my hand, and will not give unto him of my food, nor impart unto him of my substance. …

21How ye ought to impart of the substance that ye have one to another.

22And if ye judge the man who putteth up his petition to you for your substance … 23Wo be unto that man, for his substance shall perish with him. …

26Ye should impart of your substance to the poor, every man according to that which he hath, such as feeding the hungry, clothing the naked, visiting the sick.

By “substance,” he seems to have meant all material possessions: food, clothes, medicine, blankets, etc. Granted you could make the case that he also meant money to be included in “substance”,4 but I think he likely meant usable necessities because his list of suggested donations does not include money: “Ye should impart of your substance to the poor, … such as feeding the hungry, clothing the naked, visiting the sick and administering to their relief, both spiritually and temporally” (v. 26).

There are a few reasons he may have emphasized material goods (substance) over a standard unit of exchange (money). For one thing, it’s more personable, having to get to know someone well enough to assess what exactly they need. For another thing, it avoids the problem of helping someone hurt himself. If you give him something that can’t be easily exchanged for drugs or alcohol (unlike money), you can be pretty sure that you’re not enabling an addiction.5

A standard unit of exchange certainly exacerbates the potential for misuse. But consider a beggar in a moneyless society. While the problem of drugs and alcohol is eliminated or diminished, other potential problems still exist: promoting learned helplessness, dependency, or laziness. Even if the money problem were gone—even if Benjamin were speaking to ancient aborigines or Kalahari bushmen—would he still insist that we always give food, clothing, or other types of support to any and every mendicant?

Even if money were not a factor, it is clear that King Benjamin’s words could still not be construed to support indiscriminate, unconditional giving.

Judgments about True Needs

Many readers of this passage conclude that we must not make any judgments about people’s circumstances or motives, perhaps because King Benjamin says, “If ye judge the man who putteth up his petition to you for your substance that he perish not, and condemn him, how much more just will be your condemnation for withholding your substance” (v. 22). Notice, though, that King Benjamin does not necessarily forbid judging. The action that we are told to beware is “if ye judge the man … and condemn him.” While we often need to make judgments, we should completely refrain from condemning. Elder Dallin H. Oaks explains,

There are two kinds of judging: final judgments, which we are forbidden to make, and intermediate judgments, which we are directed to make, but upon righteous principles. … In [some] context[s] the word condemn apparently refers to the final judgment.6

In particular, King Benjamin seems to especially dislike the assumption that a person’s suffering is resulting from his sins or economic foolishness (v. 17). Like the Lord’s climactic speech in the book of Job, this assumption is what Benjamin cannot tolerate. However, this kind of condemning is only one form of judging; ruling out condemnation does not rule out judging all together.

Not only does King Benjamin allow judging, but he implicitly requires it at several points. In verses 19–22, he draws an analogy between beggars and mortals, saying that in a sense, all mortals are beggars because we depend on the good will of the Lord to rescue us from our painful, sinful situation. Using the conventional notation for analogies, we could say, “Rich men are to beggars as God is to mortals”:

| Benjamin’s analogy | RealitySymbol | Rich men | God | Beggars | Mortals | Begging | Praying | Giving substance | Answering prayers | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

As with all analogies, this one has obvious limitations. God is the source of everything he gives us; the rich man is a mere waypoint on the path that conveys a blessing from God to a beggar. The relationship between mortals and God is qualitatively different than that between beggars and rich men. The former is that of servant and master, while the latter is that of peers who happen to be in different situations for the moment. So our giving can never be entirely like God’s giving. A steward can’t really transfer ownership of something he’s never owned; he can only redirect the property under his care. Such is our true situation when giving the wealth that is in our hands.

However, as Benjamin’s analogy implies, there is at least one aspect of God’s giving that we are supposed to notice and emulate, and this is typified when the prophet compares our answering the beggar’s petition (panhandling) to God’s answering mortals’ petitions (prayers).

But how does God give to mortals? Indiscriminately, giving them any and everything they ask for? No, he gives us whatever will help us most, even if it’s not necessarily what we want or think we need. Benjamin points out this fact, describing God’s criteria when answering petitions: “God … doth grant unto you whatsoever ye ask that is right, in faith, believing that ye shall receive” (v. 21). Benjamin never says give whatever is asked; he says give to beggars as God gives to mortals, and God does not give whatever mortals ask for. If we truly intend to give to beggars as God gives to mortals, we must give “whatsoever [they] ask that is right.”

This obviously entails making judgment calls—evaluating the situation and trying to discern whether, what, and how much to give. This might seem like a surprising message, but it’s clear that, while warning against harsh assumptions about how the beggar got into his situation, Benjamin requires that we use discernment in getting him out of it (or helping him get himself out of it). I count nine conditional phrases or restrictive clauses that necessitate some kind of judgment on the giver’s part:

16And also, ye yourselves will succor those that stand in need of your succor; ye will administer of your substance unto him that standeth in need; and ye will not suffer that the beggar putteth up his petition to you in vain, and turn him out to perish. 17Perhaps thou shalt say: … I … will not … impart unto him of my substance that he may not suffer. …

21If God … doth grant unto you whatsoever ye ask that is right, … how ye ought to impart of the substance that ye have one to another. 22And if ye judge the man who putteth up his petition to you for your substance that he perish not, and condemn him, how much more just will be your condemnation. …

26I would that ye should impart of your substance to the poor … according to their wants. 27And see that all these things are done in wisdom and order; for it is not requisite that a man should run faster than he has strength. … Therefore, all things must be done in order. (v. 16–17, 21–22, 26–27)

These conditions might lead someone to give material goods instead of money, or to require work in exchange for the gift, or refrain from giving at all. Every situation is different, and the Spirit will help individuals discern what they should do from moment to moment that will most help, especially if they have not harshly decided that each petitioner deserves what he has. Benjamin doesn’t say no beggar deserves his situation; he says that whether the beggar deserves it is immaterial to my response. After all, I don’t deserve forgiveness for my sins, but that doesn’t prevent Heavenly Father from graciously granting it.

Conclusion

Please don’t think me a grinch. 🙂 I am not arguing for the “Never give” view; I am arguing against the “Always give” view (because both views can be harmful). By highlighting King Benjamin’s analogy and the implicit and explicit caveats he puts on giving, I hope I have clarified his intentions. When taken as a whole and in context, King Benjamin does not say that we are required to always give money to beggars, regardless of the circumstances. Instead, he teaches that, like our Father in Heaven, we should do whatever will help the petitioner most.

This, of course, implies that we must use good judgment,7 which is much more difficult than adhering to a one-size-fits-all rule. It requires that we listen to the Spirit, live worthy of it, apply wise counsel, and follow the Brethren’s example as best we can. I want people to feel free to follow the Spirit’s counsel, which is tailored to each situation and which may impel different responses at different times. It is very difficult to do so when we labor under the mistaken notion that we have been commanded to always give money to a beggar and to never use discernment to judge a situation or choose the best response. This mistaken notion can be especially taxing on our conscience when the situation is one where it is painfully clear that the beggar will misuse the money to hurt himself.

For all these reasons, it saddens me when I hear someone say in Sunday school, “Well, even when I totally know they’re going to buy drugs, I still give them the money, because that’s what we’ve been commanded to do.” I hope this examination of King Benjamin’s rhetoric will help eliminate that mistaken idea and clarify his message to Latter-day Saints. May this come in handy the next time Mosiah 4 comes up in your Sunday school class.

Notes

Image credit: King Benjamin’s Address, by Jeremy Winborg.

1. The NIV or RSV version is even a little clearer.

2. Ezra Taft Benson, “Fourteen Fundamentals in Following the Prophet,†Tambuli, Jun. 1981, p. 1.

3. They did not have coins or currency, per se, that we know of. But the Book of Mormon speaks of the Nephites having money at least four times, even though it might have been different from our modern system (Alma 1:5; 11:20; Hel. 7:5; 9:20).

4. In verse 19, he mentions gold and silver on the same list with food and raiment. However this is not on a list of things we should give, but rather of things we have received from God and should be thankful for.

5. I hope my associating homeless people with addictive habits like drugs and alcohol is not interpreted as a blanket statement about all homeless people. It’s not. I’m just saying that it’s a factor you have to consider. Simple demographics or a little experience with the homeless will quickly force a person to face that reality.

6. Dallin H. Oaks, “‘Judge Not’ and Judging,†Ensign, Aug. 1999, p. 7.

7. Yes, despite a common misinterpretation of the sermon on the mount, we are not forbidden to ever judge people in any way. In fact, we are commanded to judge—righteously. More on that in a later post.

I think it’s also important to interpret the clause, “according to his wants,” correctly. In this context (and in the era in which the Book of Mormon was translated, wants referred to something that I lack, rather than “something I desire.”

In other words, according to King Benjamin, we should impart in correspondence to what they lack, rather than what they desire.

Thanks, Jeff. I was thinking of putting that in a footnote, but I forgot.

By the way, does anyone out there know where I can find a graphic of a little child praying for a toy or some candy? I thought that would make a cute picture illustrating that not all our prayers get answered. Maybe a kid with a thought bubble above his head that shows he’s thinking of toys or candy or something.

I think I pretty much agree with this. Excellent post—it is well thought out.

I do have a couple quibbles, though. First, the questionable contradiction between two prophets could be argued to be more complicated. Canonized prophetic statements, I believe, almost always trump non-canonized statements, even (most) recent statements from living prophets. There is an endurance with what is canonized that cannot be said for non-canonized statements from dead prophets and apostles of this dispensation. I believe that it was this issue that President Benson was speaking about—I don’t think he was saying that whatever a living prophet says automatically trumps the canonized words of a (dead) King Benjamin. (I know this isn’t central to your argument, but I can’t resist.)

Second, I’m not sure if King Benjamin’s sermon can be construed to be saying that we are to give to others in the same way that God gives to his children. To be sure, I think part of the mortal experience is to become more like God in this way. Still, we receive commands to forgive all men, even though the Savior reserves His own right to forgive who He will. I still agree with the spirit of your post in this regard; I’m just not sure if the analogy to giving how God would give is (a) what King Benjamin implies or (b) correct.

Great point. I meant the use of President Benson’s principle to be an example of jumping the gun—misapplying his statement when it’s not quite called for. I’ll rewrite that sentence to make it clearer.

I also agree with your other point. We can’t emulate Heavenly Father exactly—sometimes because we’re unable and sometimes because we’re prohibited (that forgiveness thing is a really good example). I’ll add some qualifiers to that paragraph to make that clear.

This is seriously blogging at its best—free, timely peer review. 🙂 Thanks for helping me better make my point.

Changes. I made two changes:

1. After the President Benson quote: “But this kind of trump card shouldn’t be played cavalierly, especially in the ambiguous territory of uncanonized, practical, timely instructions. I believe this response assumes a contradiction that isn’t really there;”

2. At the analogy chart, the two paragraphs that include: “As with all analogies, this one has obvious limitations. … There is at least one aspect of God’s giving that we are supposed to notice and emulate. …”

Hopefully this clarifies the points Dennis brought up.

A friend of mine once got yelled at by a panhandler for giving food instead of cash.

From the personal-safety standpoint (which I do think we need to consider), I’m female, middle-aged, short, and have both bad eyesight (I do use corrective lenses) and arthritic hips which can limit my mobility. That combination of factors leaves me feeling very vulnerable when a stranger (especially a male, who’s likely to be bigger than I am) crowds into my personal space and aggressively demands money. Thus, I avoid people who look like they’re panhandling (or report them to management of stores they’re in front of) to avoid a menacing situation.

I also have enough relatives with substance-abuse problems that I just can’t see where giving money that will go to buying alcohol or drugs is a good thing. How does enabling self-destruction help the person?

I do my giving through the Church and other organizations I can trust to be using the money to HELP people break free of addiction bondage and get to where they’re self-reliant, or to provide true help to those who legitimately cannot be independent.

Those sound like the right thing to do, especially in your situation. Hopefully this article will help you and others not feel bad needlessly when King Benjamin’s sermon is brought up.

Honestly, I’ve felt that giving a couple of bucks to guys in parking lots and getting back to my life is one of the more selfish things that I can do—it puts me behind maybe ten minutes at work and keeps me from having to think about the problems this person may have or the reason they may be on the street.

Poverty in and of itself can be caused by a variety of factors, but the actual homeless are usually in even more crucial situations—crippling medical bills or debts, mental illness, and drug addictions are common. It’s hard to be an “advocate” for somebody who is hard to locate and is often in a great deal of danger, so I buy their stories for their own dignity and empty my coin purse because there’s really nothing else I can do. I’m not sure there’s a way to feel good about that.

Funding places which provide shelter, education and employment opportunities and other services is probably a better bet than food or money, which only really benefits those who put themselves out in the public eye to beg and neglects many of the homeless you wouldn’t even recognize on the street, even those with families.

By the way, I’d suggest that the “panhandlers” notification in Temple Square has more to do with preserving a particular environment in that area than any sort of grand prophetic statement. It’s clearly just a sign in Temple Square and not some sort of well-known tenet.

I agree that the signs are not an end-all, be-all instruction. We can’t conclude from them that we should “Never give.” I think the Brethren would shake their heads in sorrow if we took those signs as permission to deny the beggar’s petition at all times and in all situations.

I bring up the signs because we can conclude from them that “Always give” can’t be the right response either. They illustrate that there is at least one situation where it is appropriate to decline the beggar’s petition.

Your pictures rock! Perhaps I should try adding some to make my blog more accessible. I found many of your arguments sensible. Thanks for the thoughts! Also, check out my post on charitable giving: http://bradcarmack.blogspot.com/2009/11/do-not-your-alms-before-men.html

I want to thank you for this post. In all honesty, I only skimmed it and from that it appears that I do not agree with your arguments, but something that you said has triggered an altogether new thought/concept which has given me a deeper understanding of the gospel. So, I’m very glad that you wrote this! Thanks again!

Sure, you bet. 🙂 I’d love to hear the concept/deeper understanding that you came to. If you’re OK sharing, I’d love to know your take on King Benjamin’s message. It’s OK that you disagree. Do you mind telling how you look at it differently?