Jeffrey Thayne

|

| Ayn Rand argued that altruism is a moral evil, because it violates principles of reciprocity and leads to social decay. |

The philosophy of Objectivism includes the idea that all actions and choices are ultimately motivated by self-interest; people do things for their own benefit, whether they realize it or not. One problem I have with this idea is that it rules out the possibility of any actions that are altruistic (selfless, or purely for another’s benefit).

I recently attended a conference where the presenter, C. Bradley Thompson, defended the philosophy of Objectivism. During a question and answer session, someone asked him, “What single philosophical idea do you believe has caused the most damage to human society?” He responded immediately and confidently, “Altruism.” He argues that human beings consistently forgo actions that are in their best individual and collective interests for the sake of an unobtainable ideal that usually does more harm than good. Mutual exchange, based upon mutual self-interest, does for more good in the world than encouraging free-loaders and laziness by giving valuable time and resources to those unwilling or unable to reciprocate.

Psychologists and biologists continually debate whether true, genuine altruism is even possible in a species that is the product of biological evolution. Is it possible for a genetic trait to be passed on through the generations if this trait did not, in some way, improve the individual’s ability to reproduce? Even if this is possible, it would make the “trait” of altruism a genetic accident, an aberration in the normal course of evolution.

Most psychological paradigms treat altruism as a kind of selfishness in disguise. As Nathan Richardson explains, “[From the traditional psychological perspective], the main purpose or intent behind each action then becomes maximizing personal gain. There are two ways to do this: ignoring the desires of others, or giving space for others’ desires to increase the odds of obtaining your own desires.” In other words, we help others because doing so, in some way (either directly or indirectly), benefits us. Thus, from this perspective, altruism is simply a form of long-range self-interest. We love others because we ultimately love ourselves.

Turning the Debate Upside Down

It seems that the debate has always centered on two questions: Is genuine altruism even possible? If so, is it necessarily better than rational self-interest? Both questions, however, presume the existence of genuine self-interest. I would like to turn the debate on its head and ask a new question: Is genuine self-interest even possible?

To clarify, when I speak of self-interest, I question the possibility that the soul may be interested, focused, attentive to its own well-being to the exclusion of others. I do not dispute the fact that the self may have interests. For example, the self may pursue pleasure, enjoy music, or seek to help others, and all these things may be categorized as the “interests of the self.” However, I intend to argue that the self may not be the object of its own interests, and it is this kind of self-interest that I refer to. In a sense, it is psychological egoism that I critique.

Background: The Call of the Other

In order to lay some groundwork for why I ask this question, I’ll need to review some ideas I have previously written about. Earlier this year, I wrote a series of posts outlining Terry Warner’s ideas about self-deception and self-betrayal. These ideas are outlined in literature published by the Arbinger Institute and in Warner’s book, Bonds That Make Us Free. If you are not at all familiar with Arbinger’s work or with Warner’s ideas, I recommend that you read this series before continuing with this post. This series contains some anecdotal examples that I will reference in this post.

Simply put, Warner argues that we are constantly receiving signals from our fellow human beings about how we should treat them. In other words, we are constantly and inevitably aware of the humanity of those around us, and this humanity beckons us in general and often specific ways. These beckons present us with a choice: we can either respond to them, or we can resist them. When we resist the beckon of another person’s humanity, we do them wrong.

However, not only do we do them wrong, be we rewrite the world we see and react to in such a way that makes our wrongdoing seem right. We invent rationales and justifications for our wrongdoing, and by so doing create for ourselves a world in which our actions seem to us the only right course of action. These rationalizations often take the form ofaccusations. We often use the faults of those whom we are wronging (or we even invent faults for them) as an excuse for our wrongdoing. We cloak or mask the humanity we are resisting through accusations. For example, I recited the story of Marty, who resisted the call to help his wife by tending the baby. As he resisted this call, he also mentally and emotional accused his wife of wrongdoing towards him, citing her wrongdoing as a justification for his own.

Accusations are not the only rationalization for wronging others. Just as frequently, we cloak our wrongs in terms of self-interest. We cite our own needs as an excuse for not responding to the call of need of the Other. Again, in the story of Marty, he also determined that his own need for sleep outweighed the needs of his wife. The pressures of his job required him to sleep. I have numerous anecdotes from my own life where I have used my own needs as an excuse not to meet the needs of others. I have, for example, decided that getting to class on time was more important than holding the elevator door for someone. I have used homework as a rationale for not performing simple acts of service for roommates or friends. In every instance, I have put my own needs ahead of the needs of others, but I excused it by believing I was acting in my own best interest.

Consider: when we resist the call of the Other, either by masking the Face of the Other in an accusation or by placing our own needs ahead of the needs of the Other, we are doing them wrong. This isn’t just a passive sin of omission. When we neglect the call of the Other, we actively reinvent the world in order to justify doing it. Resisting the humanity of another person is an action, not a lack of action. An analogy is helpful here. When we push away the hand of someone who has offered a handshake, we aren’t simply neglecting to shake the person’s hand, we are actively pushing it away. According to Warner and Levinas, when the Face of the Other beckons, simple neglect is impossible. Failure to respond is active resistance.

I would like to attach a label to this wrongdoing: malice. When we actively resist the Face of the Other, we do the opposite of love: we experience malice towards the Other. Although the word is most frequently used in the passive tense (as something we experience), I mean it here in an active sense. In other words, when Faced by the Other, we have two real choices. We can either respond with love, or we can respond with malice. Simply ignoring the Face of the Other and doing neither is not an available option.

The Role of Reason in Our Lives

Emmanuel Levinas, the philosopher on whose writings many of Warner’s are based, argued that reason itself is a response to the Face of the Other. For example, to use Warner’s terminology we put our rational capacities to use in one of two ways: we can seek and discover ways to respond to the call of another’s humanity, or we can seek and invent ways to justify our resistance to the another’s humanity. Both possibilities use human reason, but for different purposes. In either case, reason was called into action in response to an obligation: either as a means of responding to it, or as a means of explaining it away.

If these are the only two responses to the call of another person’s humanity, then what of the third option, self-interest? If these are really the only two genuine options, then self-interest is simply the justification or rationale we invent for resisting the call of another person’s humanity. Simply put, altruism is not disguised self-interest. Rather, self-interest is disguised malice. It is putting reason to work in excusing our response to our fellow human beings.

In defense of this claim, I would like to recall another claim made by Warner: those who do no wrong need no rationale or justification for their actions. They need only to find the best way to do it. For example, when those who risk their lives to rescue a child from a busy street are asked why they did so, they most often respond, “Because it just felt like the right thing to do.” They certainly used reason to determine the speed of the cars on the road, how much time they had to rescue the child, or the fastest way back to the sidewalk. However, they did not use reason at all to invent a reason for their actions.

However, when someone is asked why did not help someone in need, they’ll almost always have a rationale for their inaction. Those who do wrong (and everyone fits in this category) constantly use reason to explain why they do the things they do. We invent reasons for our actions only when we feel the need to justify them. Self-interest is a reason for action. The pursuit of rational self-interest is a sophisticated, ancient philosophy that provides criteria for when we should or should not help other people, based upon the sophisticated calculus of long-term goals and desires. Those who genuinely do no wrong do not need any such sophisticated calculus to motivate their lives or to rationalize their behavior.

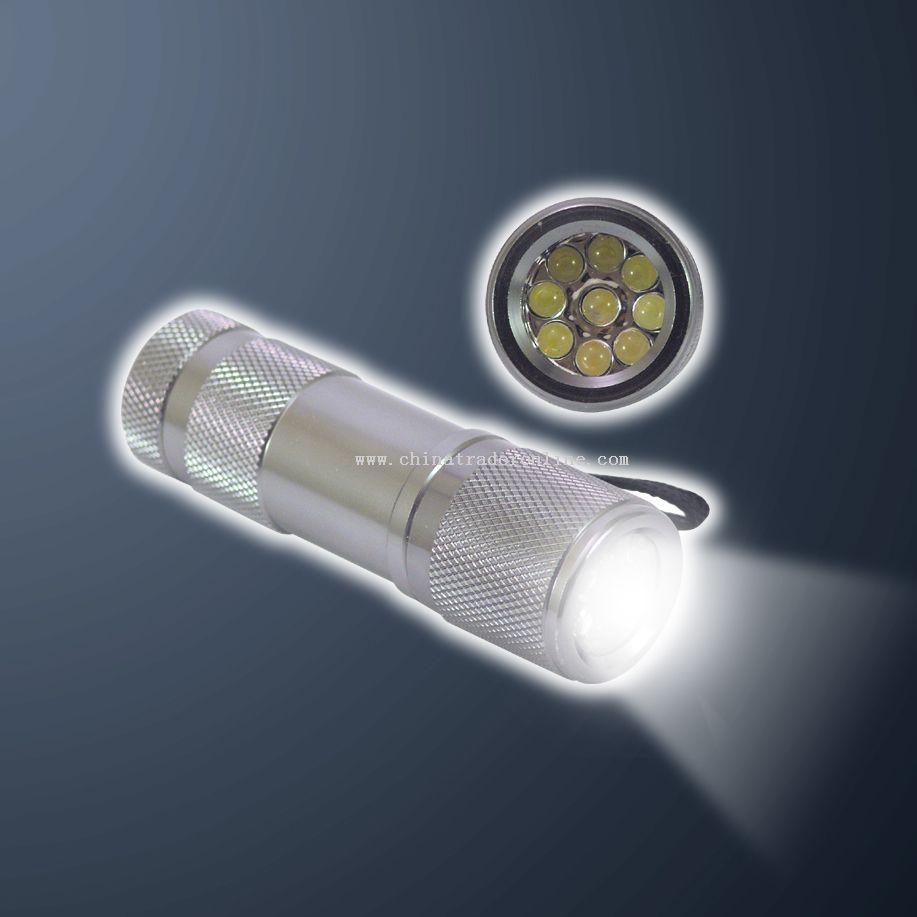

The Soul as a Flashlight

A standard flashlight can never shine light onto its own self. It can shine light outwards onto the surrounding environment, but it can never illuminate itself. I believe that the soul is much the same way: it can never be the object of its own attention, love, or interests. The soul can attend to things or people in the world around it, but never to itself. It can love things or people in the world around it, but never itself. It can be interested in things or people in the world around it, but never itself.

How then do we explain or describe self-love or self-image? James Faulconer, a respected philosopher and professor at BYU, explains, “Since by definition an image is not the real thing, the self placed at the center when one is concerned about self-image isn’t even a real self. … This is a corollary of the fact that love is necessarily of something other than ourselves: love of self is love of something that is not really our self.” In other words, love must be directed outwards, towards something in the outside world, something that is not the person who is doing the loving.

We can invent for ourselves an image of what we think we are, and direct our time and energies focusing on, fine-tuning, or serving the needs of this invented image of ourselves. By doing so, however, we are not actually focusing on our actual self, but only an image of ourselves that we have invented in our minds. We can never directly experience the presence of the self in the same way that we experience the presence of another person, and thus we can never experience an obligation to the self in the same way that we experience an obligation to another person.

In fact, I argue in this post that when we focus on serving the needs of this invented image, we are doing so as a rationale for resisting the Face of the Other. Even when we help others based upon a sophisticated calculus of self-interest, we are masking the face of the Other with an invented image of the self. And, since resistance is an active experience, not a passive one, and since resistance can best be categorized as malice, this kind of self-interest is simply a mild form of malice (although pernicious in its clever disguise). For this reason, I turn the traditional academic debate about altruism on its head and ask instead, “Is genuine self-interest even possible?”

I find it interesting and a little bit shocking that the presenter not only believed altruism was impossible, but that people’s belief in it was harmful. Talk about an upside-down world!

Thank you. This is a fascinating reversal. I need to finish Bonds That Make Us Free!

Years ago, I attended some seminars based on the work of Terry Warner. While and after I attended, I read a manuscript of Bonds That Make Us Free. About a year ago I read Atlas Shrugged.

Atlas Shrugged makes some compelling arguments for objectivism. Jeffrey Thayne makes a more compelling argument for altruism. I particularly like how he describes our moral decisions as either an expression of love or malice: “Altruism is not disguised self-interest. Rather, self-interest is disguised malice.”

Thanks Rich! I like your simplification of my post. It deserves restating: Most moral theories assume that our choice lies between serving others and serving ourselves. This moral position often advocates a balance between our focus on others and our focus on ourselves. This approach leads to many moral dilemmas, because serving ourselves is not often seen as inherent moral evil… just a little less noble than serving others. However, from the perspective offered in this post, all of our moral decisions are an expression of love or malice. This moral framework does not require the same kind of consequential moral calculus as other moral theories.

Enjoyed the thoughts. Thank you for your time in posting them and following the brethren’s exhortations that we get out the LDS viewpoints.

I find this very interesting and have several comments/questions and apologize if some of this is slightly off topic.

To me the question of self interest vs altruism gets a little complicated because acts that we would generally consider altruistic I believe are inherently intrinsically rewarding. To me the question then becomes whether people would act altruistically if there was no such reward.

I do agree that people generally act out of self interest but I believe there are many exceptions.

Economically, I believe self interest makes sense- most businesses are in business to make a profit. People enter into an ecomonic exchange if it serves their best interest. But even in business, I don’t think self interest excludes a level of altruism. For example, an altruistic employer may hire a less qualified candidate in order to help the person recover from financial or other problems, or an employer may continue to employ people out of kindness and concern for them even though the benefit provided by the employee may be less than the cost of the employee to the employer.

Can it be true that altruism is disguised self interest AND self interest is malice in disguise, or is that the same as saying that altruism and malice are the same when they are actually opposites?

There are other things I didn’t quite follow but will end my ramblings for now…

Jim: Acts that we would generally consider altruistic I believe are inherently intrinsically rewarding. To me the question then becomes whether people would act altruistically if there was no such reward.

I agree that most altruistic acts are intrinsically rewarding, and I’ve wondered the same thing. It seems to me that if a person would refrain from an altruistic act if there were no self-rewards, then it was not a truly altruistic act. I think that the more important question is what is the main reason a person does something, not whether there are other positive attendant effects.

I think you’ll find the following exchange interesting, where Jeff answered me when I asked a question very similar to yours:

Jeff Thayne, “Challenging the Pleasure Principle,” comments 9 and 10.

A few months back a friend asked me to drive him to the airport. He insisted that he would get me back by buying me lunch or something of equal value for my time and efforts. He explained to me the principle of free-exchange. I told him that, though I believe in free-market capitalism to be the best economic method of our imperfect world, I still believe there is a higher law of selflessness that Christ teaches us to live.

Disclaimer: I’m not trying to appear altruistic. I just believe we should strive to live a higher law. 🙂

That’s a great example, Jimmy. It reminds me of when my wife’s family was drawing names for Christmas gifts. She and her sister drew each other. Her sister lives several states away, and it’s hard to guess what the other wants anyway. My wife and I joked that they should just both decide to spend $20 on themselves. That way they both get what they want, and there’s no money wasted on postage.

And yet somehow, that’s not the same as exchanging gifts. From an economic, hedonistic standpoint, both options have the same result; the buy-it-myself option could even seem better. But there’s something lost. That thing that is lacking tells me that there’s something wrong with egoistic/hedonistic assumptions.

I recently read something by C.S. Lewis on this subject that I found truly profound (amazing how often it happens that something Lewis has said or written turns out to be profound). This is the opening paragraph from “The Weight of Glory,” a short sermon he gave in 1941 and was published later that same year:

The essay continues to explore and develop this theme. I highly recommend it.

I liked the CS Lewis quote from Ed. Amen.

The challenge that I have is nearly this entire argument implies some sort of a conflict between what is good for me and what is good for others. Do we really believe that there is such a conflict?

Anyone who believes there is a conflict between self-interest and charity and kindness does not understand the gospel of Jesus Christ and the abundance in God’s plan. God does not want us to give grudging gifts (see Moroni chapter 7). This means that if we are going to serve God or other men with sincerity and in a Christian manner we must WANT to do it. If we WANT to do it that means we believe it is good for us and better than the alternatives. There is never a case where a charitable act is bad for the giver. Why are we trying to divorce the ideas of self interest and charity as if they are unrelated? I think they are the same exact pursuit.

Remember that quote from Joseph Smith, (I’ll have to paraphrase) “A religion that does not require the sacrifice of all things cannot produce the faith necessary for salvation and eternal life.” Well, if I give up “all things” you would think that was selfless, no? And yet, I got Eternal life in exchange for it. Which means I was incredibly profitable, because, as it says in the D&C, eternal life is the greatest gift. The lectures on faith make it abundantly clear that every faithful action begins with a desire to improve one’s own condition. Read just the first few hundred words of the lectures on faith. This is what I think of when I think self interest.

Also remember Abraham started out simply wanting better things for himself and yet God was pleased with him and gave him what he wanted. See Abraham 1:2 (If you can’t see some self interest in THAT verse, I don’t know what will convince you…)

We ought to be grateful to God that his plan does not require suffering as the lot of mankind, but rather joy. The reason we can have faith in God is because it is clear that obedience is good for us: it makes our lives better and happier. So is it selfish to serve God? Well maybe or maybe not, but it is definitely good for me to do so.

I think maybe selfishness is more aptly described not as me doing something good for me but as me doing good for myself by harming another.

As far as altruism is concerned I think you may have mistaken the way the word is used by the Randians. Often to be altruistic means enabling people to live i ways that are out of integrity with true principles. Remember that God does not save men in their sins but from their sins. The receiver of grace must make changes to their behavior. Is their any question that government paternalism disguised as altruism is destroying individual accountability and undermining the positive influences of religion and family in our society? I don’t think there is.

I like Ayn Rand. I think she has a lot to offer as to the proper role of reason and freedom in society and relationships. I have some argument with her view that belief in God is irrational but that is a subject for another time.

Sorry I am so verbose. Please forgive the grammatical and style errors.

I don’t think anyone disagrees that there is such a thing as righteous self-service. The scriptures are abundant with promises of rewards and/or punishments which motivate our actions. The argument that some capitalists take to the extreme though is the attitude of “if there’s nothing in it for me than I’m justified in not doing it.” But when members of a church are taught to give all of their time, money, and talents to the church they are being taught something higher than a principle of free-exchange. They are being taught sacrifice. If I consider a calling in the church to be inconvenient and I don’t see any benefits for myself in continuing to fulfill that calling then my attitude is selfish.

I like Ayn Rand too and I agree with her most of the time. But we need to be careful when mingling the philosophies of man (or woman) with scripture when they don’t line up. Scripture is truth. It doesn’t change. Philosophies of man are random and always changing.

Jon,

I think we all agree that there are blessings connected to righteousness. I think we’ll all agree that doing the right thing is always, in the end, better for us than doing otherwise. I think the question at hand is not whether or not good consequences ensue from right actions, but why we act in the first place. The issue here is motivation.

You said, “If we WANT to do it that means we believe it is good for us and better than the alternatives.” Is this always true? Are we always thinking of ourselves when we want something? For example, if I want to mow the lawn for my neighbor, am I always weighing that decision against the possible rewards and consequences for myself? I believe that we sometimes (if not often) do things because we want to do them for others, not because they are better for us (even though they may be). Again, the issue here is why we do what we do, not whether or not we profit from it.

“Is their any question that government paternalism disguised as altruism is destroying individual accountability and undermining the positive influences of religion and family in our society? I don’t think there is.”

I don’t think there is either. But this is not the kind of altruism I’m talking about… not is it altruism at all, because coercion is born of malice, not love, and coercion is the essence of government. So you’re right here… but it doesn’t negate anything I’ve written in my article.

I don’t believe I misread Ayn Rand when she says that altruism is a moral evil. Of course, she is criticizing paternalistic government, but she falsely lays the blame on altruism, when the real culprit is malice and a lust for power. She even goes further: she argues that it is not only evil, but genuinely impossible. She argues that genuine altruism is motivated by a hatred of those who succeed, and is therefore a mask for hatred, not love. Now, she has room in her philosophy for people to help others because they believe it is best for themselves to do so… but to help others purely for the sake of the Other is frowned upon. This strikes me as being as unchristian a philosophy as there ever was.

I’ll respond as I read–

I like this post! I wrote about selflessness too (http://bradcarmack.blogspot.com/2009/10/selfless-satan.html).

PS, do you know why my picture doesn’t show up on these comments?

I like that you turned the conventional wisdom on its head – Leavitt and Dubner do the same thing in their Freakonomics series. Of course, if you’re successful at turning the conventional wisdom on its head, your exegesis becomes the conventional wisdom, subject to the next bright guy’s turning- but then that’s one of the beauties of science, right? A contest of ideas where those that hold the most water rise to the top?

I wonder why your construction of self-interest is exclusive to start out.

Yay Terry Warner and Arbinger! Leadership and Self-deception and Anatomy of Peace changed my life. I have yet to complete “Bonds that Make Us Free.”

I buy into the receiving and sending signals to others concept, and find the signaling nearly equivalent to a species of “personal influence” (“We cannot escape the influence of our personal influence” http://www.lds-quotes.com/?action=quotes&topic=32).

It sounds like you’ve heard or read some of the same stories I have- I think an Arbinger Institute leader shared that same Marty story in a training he did for the Fourth Judicial District at UVU campus last Fall for Judge Jon Memmott, that I TA for.

Yep, entering and reinforcing the box is an act of commission.

I am initially persuaded: “Simply put, altruism is not disguised self-interest. Rather, self-interest is disguised malice.”

Hmmm- I’m considering whether the soul is a unidirectional outward attention. What’s your support for the claim? Could be true – hmmm.

“We can never directly experience the presence of the self in the same way that we experience the presence of another person, and thus we can never experience an obligation to the self in the same way that we experience an obligation to another person.” Okay, I buy this so far…

The sophisticated long-term calculus can be passive and thoughtless, thought. That’s part of the idea I think of the natural selection conception of altruism- the actor need not perform the calculus, for the behavior patterns which result in proliferation of selfish genes are conserved. Much as you don’t need to understand the unimaginably complex chemistry of digestion in order to benefit from breakfast, you may conceivably benefit from complex self-interest formulas without personally doing the math simply as a consequence of one’s genetic heritage.

Insightful idea, though- I found it valuable and I got a little excited to see someone else directly using the Arbinger paradigm/worldview that I share.