Jeffrey Thayne

|

| I could easily have given up the seat next to me on the bus, but I didn’t. Why not? |

During the fall semester of 2007, I rode the UTA bus from Elk Ridge to BYU campus each day. Some days the bus was pretty busy, and other days there were very few people on the bus. One particular morning, I was reading a book while in transit to Provo. Most of the seats on the bus were occupied, but the seat next to mine was one of several that were still left open. The bus stopped, and two or three people got on the bus. I enjoyed having the entire seat to myself, and I knew that there were enough other seats on the bus for each of the new passengers. I made the seat next to mine look as uninviting as possible by placing my legs on the seat, and then buried myself in my book to avoid eye contact with the new passengers. I freely admit that I was in the wrong. I saw the new passengers as nuisances, potential distractors from my reading. I considered my desire to have the whole seat for myself as more important than their need for somewhere to sit.

One day, I climbed aboard the bus, and there were a few seats open. One was next to a student near my age, who was busy reading a book. As I approached, he looked up at me, made eye contact, smiled, and made room for me to sit. This student was reading a book while sitting next to an empty seat (just like I was before), but he didn’t see others as nuisances, and didn’t see his wants as more important than the wants of those around him. Rather, he saw my need for a place to sit as equally important as any desire he may have had to sit alone. In fact, he seemed to welcome my presence. This gesture of kindness provided me with a remarkable example of something I have read about in three books: Leadership and Self-Deception, The Anatomy of Peace, and Bonds that Make Us Free (all of which are published by the Arbinger Institute).

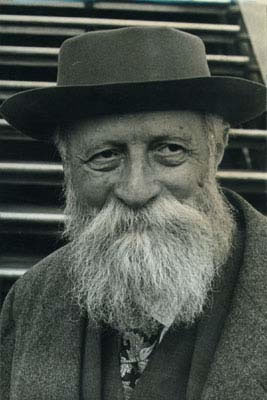

Martin Buber

|

| Martin Buber was a Jewish philosopher, scholar, and translator. He lived from 1878 to 1965. |

According to the book Anatomy of Peace, the Jewish philosopher Martin Buber

observed that there are basically two ways of being in the world: we can be in the world seeing others as people or we can be in the world seeing others as objects. He called the first way of being the I-Thou way and the second the I-It way, and he argued that we are always, in every moment, being either I-Thou or I-It—seeing others as people or seeing them as objects.3

In other words, Buber believed that human experience oscillates between two different kinds of relationships: “I-Thou” and “I-It.” We sometimes experience others as objects that can either assist or hinder us in the pursuit of our own desires and wants (which take precedence over the needs or desires of others). When we experience the world this way, we see people as we see any other object in the natural world: items of interest that can be analyzed, explained, observed, described, or manipulated.

Other times, we experience others as people who have needs, desires, and an existence that are of equal importance to our own, to whom we are obligated to treat with dignity and respect. Jeffrey Reber explains, “The I-Thou relation happens when there is a direct, unmediated meeting with another being, not as an object or a thing to be experienced, used, and explained, but as a Thou, a You, to be met, responded to, and shared with.”1 The I-Thou relationship is something that can never be encapsulated in any scientific observation, description, or analysis, because talking about the I-Thou relationship that way inherently reduces it to something that it is not. It is an experience of another human being as something other than us, something that is fundamental irreducible, something that can call upon us in ways that mere objects cannot.

We are fundamentally different people in each of these two relationships. Reber explains, “The hyphen in the I-It and I-Thou relation is very important … because it signifies the inseparability of the I from the It or Thou. … As Buber puts it, ‘The I of the primary word I-Thou is a different I from that of the primary word I-It.'”1 In other words, the way we relate with the world around us affects who we are. There is no self that is separated from the surrounding world, and no part of the self that isn’t affected by changes in its relationship with the surrounding world.

Two Ways of Being

When I was reading on the bus, I saw others as objects that could either hinder or assist me in my own pursuits and desires. I didn’t see them as people, like the student I met on the bus a few days later. He saw others as what they were: people with needs, desires, and wants that are equally as important as his own. I would venture to say that I was experiencing an “I-It” relationship with those around me, and he was experiencing an “I-Thou” relationship with those around him. Clearly, I did not see people the way they actually were, because their needs really were as important as mine, and they really are something more than nuisances. Because the I is radically different in each kind relationship, these two relationships describe two different ways of being in the world.

I believe that every action and every outward behavior can be done in two different ways. The book Leadership and Self-Deception uses the terms “in the box” and “out of the box” to describe these two different ways of being. The book The Anatomy of Peace uses the terms “a heart at war” and “a heart of peace” to describe these two different ways of being. The book Bonds that Make Us Free uses the terms “resistant” and “responsive” to describe these two ways of being. While none of these terms are used by Buber himself, they each reflect different ways in which we experience these two kinds of relationships. Buber himself preferred the terms “I-It” and “I-Thou.” Why each of these terms describe the same phenomenon will be the topic of a future post.

The central point is that the difference between the two experiences is not necessarily what a person does, but the way a person is being in the world. In other words, the difference is not behavioral. The way we see the world, others, and ourselves is radically different, even though our actions may be the same. Of course, the two different ways of being may eventually lead two people to act differently, just like the student on the bus acted differently than I did. However, at some point prior to the new passengers boarding the bus, my external behaviors were identical to the behaviors of the student, even though my relationship with the surrounding world was dramatically different than his.

Another experience illustrates this: Once, in high school, I was in a computer lab working on an assignment during class time. A friend of mine began to whisper to me, and we became absorbed in a conversation about after school activities. Soon, the classroom instructor chastised us for not paying attention in front of the whole class. I was startled and felt belittled, and sensed that the instructor was annoyed with us. A few weeks later, I was in a choir rehearsal when a friend and I began to converse about something unrelated to the rehearsal. The choir instructor chastised us both in front of the whole class for not focusing on the task at hand. However, on this occasion, I didn’t feel embarrassed or belittled.

The instructor used the same words when he chastised us that the classroom instructor used weeks earlier. However, there was something qualitatively different about the experience, because I sensed that the choir instructor cared about us, and that he didn’t see us as nuisances, but as students with potential. He respected us. The same words (even in the same tone of voice!) had a qualitatively different effect, because the person saying them saw others in a fundamentally different way. Just as much as people respond to what we do, if not more, they respond to the way we are while we do it.

I have included these two examples only because they clearly illustrate the point I am trying to make. In reality, every experience illustrates this point, because every action is undertaken in one of these two modes of being. Whenever we act, we act with a heart of peace or a heart at war, out of the box or in the box, responding to others or resisting others, or in an I-It relationship or an I-Thou relationship. Anatomy of Peace explains, “Buber’s observation of these two ways of being raised the question of how we move from one way of being to another—from seeing people as people, for example, to seeing others as objects, and vice versa. But this is a question Buber never answered. He simply observed the two ways of being and their differences.”2 In my next post, I will explain how we can move from one way of being to another.

Notes

1. Jeffrey Reber, “Buber’s ‘Between’: Ontological, Epistemological, and Spiritual Implications of a Fundamental Relationality.”

2. Anatomy of Peace. Published by the Arbinger Institute.

Such a simple, yet subtle formulation! I-thou; I-it. And yet it encapsulates all of the beauty and all of the horrors of the relational and “irrational” world.

I associate relationality with knowledge sharing, rather than bus-seat sharing, but when you get down to it, they are rather intimately connected, as you show.

Thanks for this.

Thanks for your comment, Neil! We appreciate it when we here from our readers. We hope that you continue visiting our site. I enjoyed my visit to yours.

What did you think of the rest of this series?

Where can I read what you say about Buber’s ‘between’?

Thank you.