|

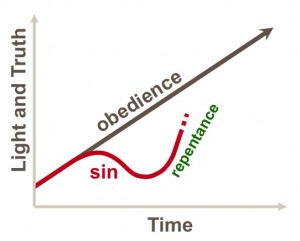

| Obedience versus Repentance. Sin definitely interrupts the steady growth that comes with obedience to God, but where exactly does repentance lead to? |

In a previous post (“I Am the Way … Unless You Find a Better One”), I introduced a chart used by Elder Merrill J. Bateman in a CES fireside broadcast. On it, he draws two lines, one showing the uninterrupted progress experienced through obedience to God’s will, the other showing a dip caused by sin and a rising again caused by repentance. One question remains unresolved on Elder Bateman’s chart: Where does repentance lead us, in comparison to what our condition would have been had we never strayed? In other words, where should Elder Bateman’s sin-repentance line end?

Mistaken Answers

Occasionally people suggest, “It seems like I’m better off for having sinned and repented, because I learned so many things in the process that I wouldn’t have learned if I hadn’t strayed from the straight and narrow path.” If this were true, we would complete Elder Bateman’s graph by making the sin-repentance line continue rising above the obedience line, since the path of sin and repentance would lead to greater light and truth, growth and progress, than perfect obedience does.

But modern prophets have strongly excluded this idea. For example, Spencer W. Kimball said, “This simply is not true. That man who resists temptation and lives without sin is far better off than the man who has fallen, no matter how repentant the latter may be.”((Spencer W. Kimball, The Miracle of Forgiveness (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1969), pp. 339–60; cited in Spencer W. Kimball, “God Will Forgive,” Ensign, Mar. 1982, p. 2. The omitted portion, indicated by ellipses, brings up an interesting point that I will address in another post.))

A more common, and understandable, mistake is to suggest, “You are forgiven when you repent, but the progress and growth you might have had through obedience can never completely be recovered.” If this were true, we would complete Elder Bateman’s graph by making the sin-repentance line level out below the obedience line, since the path of sin and repentance could never fully repair the damage to your growth and progress.

However, modern prophets have also taught against this idea as well. For example, Boyd K. Packer said, “If you have already made bad mistakes, there are ways to fix things up, and eventually it will be as though they never happened.”((Boyd K. Packer, “The Spirit of Revelation,” Ensign, Nov. 1999, p. 23. See also Vaughn J. Featherstone, [source].))

Full Recovery

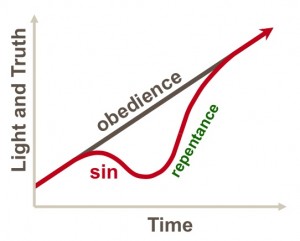

|

| True Doctrine. Prophets have clearly taught that repentance can fully restore all the progress and growth lost through sin. |

It is clear from Elder Packer’s quote that, in spite of sin’s serious and deleterious effects, we can fully recover all the growth, progress, and joy—the “light and truth”—we have lost. The prophets really mean it when they say, as far as sin is concerned, it can be “as though it never happened.” If we really understand this doctrine, we are obliged to complete Elder Bateman’s chart by drawing the sin-repentance line so that it rises until it meets with the obedience line. The path of sin and full repentance ultimately leads us, not higher or lower, but exactly to the same condition we would have been in if we had been as perfectly obedient as the Savior himself. That is the power of the Atonement, and anything less would ignore many promises made by the Lord himself.

However, this begs the question, “Then why did President Kimball say it’s better to not sin?” That’s a valid point. If repentance fully restores us, then how is obedience better? How do we harmonize these two doctrines? How can we be “far better off” being perfectly obedient, if sin and repentance can make things “as though they never happened”?

Mortal Limitations

One key to this apparent dilemma is found in one word in Elder Packer’s quote: “eventually.” It is true that we can be fully restored, but such promises almost always include caveats like the word “eventually” or “some day.” For example, Joseph Smith spoke of the “principles of exaltation” and said,

It will be a great while after you have passed through the veil before you will have learned them. It is not all to be comprehended in this world; it will be a great work to learn our salvation and exaltation even beyond the grave.((Joseph Smith, “The King Follett Sermon,” Ensign, Apr. 1971, p. 13-14.))

To add a twist to Robert Frost’s poem, it appears that each can say we have “miles to go [after] I sleep.”((Robert Frost, “Stopping By Woods on a Snowy Evening.”)) While Brother Joseph seems to have been focusing on knowledge and principles, I think this idea applies to the restoration of lost progress as well.

Randy Bott, a religion teacher of mine, often speaks of temporal effects of sin and eternal effects of sin. The eternal effects can be readily made up for by the atonement, but we are often left with temporal effects that continue during our mortal life and affect us until the day we die. For example, a girl may be forgiven of fornication, but that will not remove the baby in her womb (of course, that baby can become a blessing). Or, I may be forgiven for snapping at my wife, but once I’ve developed a habit, it may be hard to eliminate for the rest of my life.

I do not mean this to be discouraging, nor to downplay the amazing promises we have received about full repentance. But it would be unrealistic and a disservice to ignore the far-reaching effects of sin. Even the most righteous and penitent person is still essentially “broken” to some degree until the consummation of our forgiveness after this life. In fact, a thorough understanding of our brokenness helps us appreciate just how much the Savior has done for us.

Conclusion

We can be fully forgiven, to be sure, and many lost blessings can be regained in this mortal life. But that plenary restoration of all lost blessings will not come completely until “beyond the grave.” And until then, we must sometimes continue to shoulder some of the effects of our choices. Thankfully, as Elder David A. Bednar teaches, the Atonement not only provides forgiveness of sin, but empowering grace that enables us to continue until the race is won.((David A. Bednar, “In the Strength of the Lord,” BYU-Idaho devotional, 23 Oct. 2001, speeches.byu.edu.))

I enjoy the topic of repentance in this post, but I am not sure I agree with the idea of linear progression. To think of our lives as “better” or “worse” than another’s. Or to think or our condition as “better” or “worse” than if we hadn’t sinned (or whatever) seems off to me. Where does that lead us? I do agree with the main point of the article: we can be fully forgiven of our sins, as though they’ve never happened. And this is thanks to the eternal sacrifice of our Savior. Too many people simply don’t accept this as a reality; they pay lip-service to this, but their practice and judgment suggests they believe otherwise.

It’s not helpful to me to wonder about my linear progression; nor is it helpful to my children if I hem and haw over whether they are “better” or “worse off” than if they hadn’t sinned; or better or worse off than a neighbor who has or has not done such and such. An alternative way of approaching this? Just leave out the entire concept of better-off or worse-off. We have faith, we repent, we can be forgiven, we move forward . . .

Thanks for your comment, Aaron. When I tried to think of a visual way of representing the idea I wanted to get across, I knew there was a big possibility of ambiguity, as with any graphic and especially with math-type ones.

I didn’t mean to imply that progression is linear, only that obedience helps us progress. That’s why I didn’t put any units on either axis. “Time” in this case can mean a series of choices, not so much seconds or years. “Light and Truth” can mean joy or peace or whatever best illustrates that obeying the Lord’s will is the way to do things. Each point is further on than the point before it, but to what degree is unimportant and hence not indicated; all that matters is that with God, things keep getting better. That’s the only idea I want to indicate by a line with a positive slope. Unfortunately, quantitative graphics carry with them some baggage that’s hard to leave behind. 🙂

And I really didn’t want people to compare their condition to their neighbors’. I can see how President Kimball’s quote could be taken to imply that. But I think he and all the prophets main purpose is for each individual to compare his condition to other possible conditions he himself might be in, and choose wisely which one to pursue. Thanks for helping me clarify that.

And you’re right, being overly obsessed about “what might have been” can lead us into despair. I wonder if that’s why Alma said, “Only let your sins trouble you, with that trouble which shall bring you down unto repentance” (Alma 42:29). If it begins to bring us down into despair, then the thought experiment has ceased to be useful and we should stop. But I feel like we can choose our response. Where does pondering our possibilities lead us? Hopefully to repentance. I feel that if we really understand the Atonement, then it fills us with hope because we can fully acknowledge the mess we’ve each placed ourselves in (in big and small ways) while still having a bright hope that in the end, nothing worthwhile or good will be lost.

Thanks again for your thoughts. I get excited every time I see your name in the “Recent Comments” widget because I love your comments!

I have been really intrigued by this series. I came across it while reading your series on Spiritual Death. I have two main questions that haunt me as I’m reading through both of these. I don’t mean to argue with anything you’ve written at all. In fact these are some concerns that I’ve been wrestling with for some time, and I hope this might be a place for me to get some insight into my own dilemmas.

The first relates to the title of this post. Elder Hafen explained that as we apply the atonement to the opposition in our lives, we aren’t taken back to Eden. Even after Adam had fully repented of his transgression, returning to Eden wasn’t his goal. He didn’t want to become innocent and naive again. So it seems to me that this contradicts the notion that the atonement makes things as though the sin had never happened. That assumption feels to me like somehow all of our sin as well as Adam’s fall, are an accident that God wished wouldn’t have happened.

I guess this leads to the problem I have with saying someone would be better off having __________ (anything) because it suggests that God allowed something to happen that was not in the best interest of one of His children when it could have been otherwise. This assumption requires that God is somehow lacking in either his omniscience, his omnipotence, or his benevolence.

This is kind of the tie-in between problems one and two for me. Two centers around accountability and agency. My life experiences have led to me believing that mortality can ensnare us and trap us without our having full agency in the matter. (I’ll show how this isn’t true later.) But if a child isn’t accountable and capable of sin before 8, what happens to a child who before that time becomes warped by the sins of others (the traditions of the fathers) and, for example, addicted to nicotine. I have a problem with the logic that says this child (now 8 years and one day old) is fully capable of making the choice whether to sin (smoke) or be righteous, and any compromise of that agency must be due to her own sin. With all of the ways that children can be molded and influenced, I struggle with the age of 8 magically bringing with it a complete agency and accountability. I haven’t fully reconciled this issue.

Back to agency and our own involvement in sin, I believe the answer to the paradox lies in the preexistence. I don’t believe that God would send us to earth with any surprises. I don’t think anyone would be justified returning to the Judgment and saying, “Hey, that was unfair. I wouldn’t have agreed to take the risk of leaving if I knew how hard it would be.” Instead I think we were given the opportunity to give our fully informed consent to the experience.

I would argue that in order to be fully accountable, we must be fully informed. Not only of what God says is right or wrong, but of the consequences of our choices. So all of our choices lie somewhere along a continuum between fully ignorant and not accountable (in which case the Savior takes care of everything unconditionally, like babies who die and people who die without the Gospel) and fully informed and accountable, in which case everything rests on us and the Atonement has no power (I think this is what is meant by sons of perdition). To all of our choices there is a component that is simply part of mortality that we don’t have to repent of, and a component of personal sin which requires our repentance in order to be cleansed. The beauty here is that the Atonement’s infinity can deal effectively with parsing out which part is which. So if our act to consent to the conditions of mortality in the preexistence is the source of bitterness in our lives, that must be viewed in the same light as Adam’s transgression—perhaps our own individual transgressions? In which case it is necessary for our salvation and progress.

So that makes me wonder about President Kimball’s comment that we are always better off not sinning. If that were the case, wouldn’t God have made it possible for us to go through life without sinning? I’m not convinced by the argument that this means that we learn faster than the Savior or that we can be learn better than the Savior. In general, I have concerns about how literally we rely on the analogy of us being in a similar circumstance as He was. I think that it is safe to say that a man who lives perfectly obedient still falls short of the glory of God. He is still not able to save himself. He still needs Christ to make him holy, to bestow upon him those attributes that God has that we are not capable of developing ourselves. This is a trap I fell into myself. For many years in my life I was obedient and kept the commandments diligently. I avoided a lot of pain associated with sin. I also lacked charity, humility, faith, and any sense of reliance on the Savior. It wasn’t until I had seriously strayed from the path that I was able to develop those things. I think that if repentance for sin is the end of the process, then yes, sin only leaves us back in the exact same place except having experienced more pain and suffering than had we just kept the commandments. We will have cleared the weeds out of the flower bed and it will be as pure and empty as if they had never been there.

BUT if through the process of repentance we learn the skill of relying on Christ, of having a broken heart and contrite spirit, of opening ourselves up to his grace, if we develop those skills, we will be better prepared for the process of sanctification which comes after a remission of sins. I tend to believe that anything which leads us to develop those skills is a gift from God.

This is total rambling and I don’t know if there is even anything worth responding to, but I think I’m better off having vomited it all up. Thanks for making me think!

Can I just say again how awesome I think you guys are? Thanks for your thoughtfulness and willingness to really ponder this stuff!

Hey Kevin, good to “see” you again!

Have you read the other companion series to this one? The series Spiritual Death and the series The Path of Sin are meant to go hand-in-hand with a third series called The Path of Adam’s Fall. I intentionally titled the two “path” series similarly in order to draw a contrast.

The simplest way to answer some of the questions you raise, is to make this observation: you seem to be confusing the Fall of Adam with personal sin (sometimes called “the fall of me”). They’re two distinct things, and we have to keep them separate in order to make sense of pain in life. Adam’s fall, and the resulting pain and sorrow of mortality, was necessary; personal sin, and the resulting misery and spiritual darkness, was not. (I guess I’m stealing the thunder I was planning for my next series by pointing this out now, but I intentionally drew the charts of the two “path” series to look similar, in order to show the contrast.) I think there are some important quotes from modern prophets that would help you out, especially in part 4 of The Path of Adam’s Fall, “Falling Forward.” I bring this up because of some assumptions that underlie your questions. I hope I can explain it well, but if I don’t, please let me know if it doesn’t make sense.

Kevin: Elder Hafen explained that as we apply the atonement to the opposition in our lives, we aren’t taken back to Eden. Even after Adam had fully repented of his transgression, returning to Eden wasn’t his goal. He didn’t want to become innocent and naive again. So it seems to me that this contradicts the notion that the atonement makes things as though the sin had never happened.

I think it’d be safe to say that the Atonement makes it as though sin never happened, but it doesn’t make it as though pain and sorrow never happened. I did some Googling, and I think I found the quote from Elder Hafen that you’re referring to (thanks for bringing it to my attention—I might add it to one of my posts). Keep in mind, though, that Elder Hafen is talking about the Fall of Adam, not sin (“the fall of me”):

The trouble here is treating Elder Hafen’s comments about Adam’s Fall as though they applied to sin. Elder Hafen has said elsewhere,

Since Adam’s Fall wasn’t a sin, it makes sense to say that the Atonement preserves the good lessons that could only come from the Fall, but it eliminates all the spiritual debris that comes from sin. In fact, the introduction that the previous quote comes from is entitled “The Atonement is Not Just for Sinners.” I haven’t read the book, but I’m guessing that his point is the same one I’ve made with the two “path” series: there’s sin, and then there’s pains of mortality, and they are qualitatively different, even if we sometimes use the same words to describe them, like “sorrow” or “misery.” (I recently saw an LDS book entitled Weakness is Not Sin. I haven’t read that on either, but my guess is that the author is making this same point.)

Once we understand this distinction, a few of your questions can be answered more clearly.

Kevin: That assumption feels to me like somehow all of our sin as well as Adam’s fall, are an accident that God wished wouldn’t have happened.

Our sin is an accident that God wished hadn’t happened. Adam’s Fall was not an accident, and God wanted it to happen.

Kevin: I guess this leads to the problem I have with saying someone would be better off having __________ (anything) because it suggests that God allowed something to happen that was not in the best interest of one of His children when it could have been otherwise. This assumption requires that God is somehow lacking in either his omniscience, his omnipotence, or his benevolence.

This get into “theodicy,” or the problem of evil, which whole volumes have been written on. The most concise way I can think of to address it here is, yes, God does allow some things to happen, that could have been otherwise, that are not in his children’s best interest. This is in part because he values agency so highly—another topic that could consume volumes. To put it concisely again, he values agency because the freedom to fail and rebel are what makes success and and submission meaningful when we choose them.

Kevin: I struggle with the age of 8 magically bringing with it a complete agency and accountability.

I, too, doubt that children immediately acquire knowledge of good and evil where none existed before, on their eighth birthday. The scriptures certainly don’t say they do. We’ve been instructed to baptize only people over eight (D&C 68:25, 27), but I think that’s probably for practical reasons, like to have uniformity in a large Church. Accountability probably comes in degrees over a long process taking years. There are probably several five-year-olds who are already pretty accountable. But the fuzzy areas will probably be taken care of through grace and vicarious ordinances.

Kevin: I believe the answer to the paradox lies in the preexistence. …

Very insightful thoughts. Now I think about it, David O. McKay said something similar. He said that some mortal situations

Kevin: What happens to a child who before that time becomes warped by the sins of others (the traditions of the fathers) and, for example, addicted to nicotine. … To all of our choices there is a component that is simply part of mortality that we don’t have to repent of, and a component of personal sin which requires our repentance in order to be cleansed. The beauty here is that the Atonement’s infinity can deal effectively with parsing out which part is which.

I completely agree with that statement; I think you put that very well. I’d like to add that, if you keep in mind the distinction I mentioned above, we can connect that “component that is simply part of mortality” to Adam’s Fall, and that “component of personal sin” to our personal fall, or sins.

Kevin: So if our act to consent to the conditions of mortality in the preexistence is the source of bitterness in our lives, that must be viewed in the same light as Adam’s transgression—perhaps our own individual transgressions? In which case it is necessary for our salvation and progress.

Take out the phrase “perhaps our own individual transgressions?” and I’d agree with that idea as well.

Kevin: [If] we are always better off not sinning … , wouldn’t God have made it possible for us to go through life without sinning?

I’m still pondering this one for myself. Sometimes I wonder if it is possible, but no one ever does, except the Savior … which could be an even harsher indictment of human beings than depravity. But another explanation is that that’s the legacy of Adam’s Fall, where even if we have a pure and innocent spirit, from day one we’re tangled up so much with a carnal body and wicked surroundings that we can never navigate our way out of the maze of sinful surroundings without getting wounded and dirty (maybe this is what the Lord was explaining to Adam in Moses 6:55). Either way, though, God would cover us with grace for anything that was truly beyond our abilities to avoid.

Kevin: I think that it is safe to say that a man who lives perfectly obedient still falls short of the glory of God. He is still not able to save himself. He still needs Christ to make him holy, to bestow upon him those attributes that God has that we are not capable of developing ourselves.

I agree, in part because we still need him to resurrect us and purge from us the fallen parts of us that we are born with.

Kevin: For many years in my life I was obedient and kept the commandments diligently. I avoided a lot of pain associated with sin. I also lacked charity, humility, faith, and any sense of reliance on the Savior.

Well, those last items are sins in themselves, so I guess you could say you only thought you were keeping the commandments. 🙂 I think we all come to that realization eventually.

Kevin: If through the process of repentance we learn the skill of relying on Christ, of having a broken heart and contrite spirit, of opening ourselves up to his grace, if we develop those skills, we will be better prepared for the process of sanctification which comes after a remission of sins.

I, too, have learned those same lessons from my sins—powerful, transformative lessons that have been the means of teaching me Christlike virtues. The question we have to ask is: “Is that the only way I could have learned those things?” I firmly believe the answer is No. As you said, even a perfectly obedient mortal would still need to rely on Christ. Our hypothetical perfectly obedient mortal has no sin, but he still has weakness. So he would still need to call on God for strength beyond his own. I believe such a person could still learn all those Godly virtues through means and experiences that don’t involve sin. And that’s what indicts us sinners—because we didn’t have to sin in order to learn those things.

Sorry this was so long. I hope it makes sense. I’m glad that you’re so thoughtful about this and willing to ponder it.

Thanks so much for your thoughtful comments. I’ve been pondering this stuff a lot and have a couple of additional ideas.

Nathan: The trouble here is treating Elder Hafen’s comments about Adam’s Fall as though they applied to sin.

In reading both Elder Hafen’s Ensign article entitled “Beauty for Ashes” and his book “The Broken Heart,” I get the feeling that the line between “sin” and “fall” are not so easily separated. Part of our dilemma rests in our basic understanding of the nature of sin. I wrote about that in a religion paper here.

I wonder if part of our “problem” isn’t related to the doctrine taught in D&C 19 that the Lord sometimes speaks to us in a manner that is intended to motivate us-even if it leaves us with a cloudy view of reality. Sin, it seems, is really hard to define. I’ve heard of “sins of omission” and “sins of commission.” I’ve heard of lacking Charity as a sin, and yet what mortal ever attains the level of Charity God has? How often are we left to choose between two choices that are neither really good, but one is clearly less “sinful” than the other. The prophet Joseph Smith taught that what is wrong in one situation may be and often is correct in another. I’m not arguing for complete moral relativity here. I’m not saying that sin doesn’t exist. Clearly there is a right and a wrong and all mankind is born into the world with the Light of Christ which helps them discern between the two.

But I have come across a couple of ideas that, for me, neatly bridge the gaps. First, I wonder if there isn’t in reality only one sin. Everything else is simply an outward manifestation of this single act. It is closely related to pride, which President Benson claimed is at the root of all sin. I think this sin is refusing the Atonement of Jesus Christ. We are only bound by the chains of sin or the chains of the traditions of our fathers so long as we resist turning to Christ who will free us of the chains that bind us. It is only through His atonement that we have the ability to escape the snares of the adversary. This is particularly true for sins of omission. We are constantly bound by covenant to do far more than we are able. Only through the enabling grace of the Atonement can we accomplish what we’ve covenanted to do. (For a fascinating read on the power of covenants, particularly marriage, see Elder Hafen’s book Covenant Hearts.)

So for me the actual outward manifestation of “sin” is quite irrelevant. The degree to which I am bound by Satan or to which my ability to choose is limited by my mortal circumstances is more or less arbitrary. It seems unjust of God to selectively limit this person’s choices here and limit another’s there and yet hold them to the same standard. In light of all the ways in which our choices can be limited whether through sin or simply a fallen world, Agency has always been a bit tricky for me. Until I realized that the only choice that really matters is whether or not we turn to Christ and accept the Atonement (the powers of which go so far beyond resurrection and remission of sins.)

Nathan: Take out the phrase “perhaps our own individual transgressions?†and I’d agree with that idea as well.

I think I was unclear here. I was suggesting that our act of Agency to come to mortality and submit to the circumstances of a fallen world may be considered our own personal transgressions which would, in fact, be analogous with Adam’s transgression. I agree with you that “sin” would be qualitatively different than this type of transgression.

Nathan: But another explanation is that that’s the legacy of Adam’s Fall, where even if we have a pure and innocent spirit, from day one we’re tangled up so much with a carnal body and wicked surroundings that we can never navigate our way out of the maze of sinful surroundings without getting wounded and dirty (maybe this is what the Lord was explaining to Adam in Moses 6:55). Either way, though, God would cover us with grace for anything that was truly beyond our abilities to avoid.

I think that this passage in Moses provides an important insight. To me it gives hope to the sinner. It suggests that the reason he got tangled up in sin in the first place is not due to some character flaw that makes him unworthy of being saved. But given the view of sin and agency above, it provides no degree of justification to the sinner for remaining in sin. In a sense I kind of believe that what is in the past was predestined to be just that way. God knew it was going to happen and still knew that it would be in my best interest to send me into those circumstances of morality anyway. However, what is happening now and what happens for eternity. . . all depends on the degree to which I accept the Atonement and let Christ work in me.

Thanks again for providing a place where this kind of stuff can be discussed!