Nathan Richardson

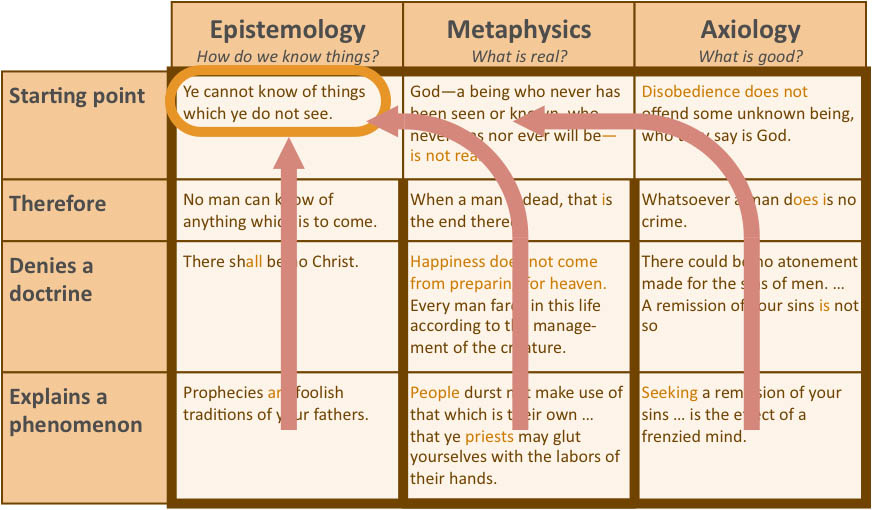

| Recap: Korihor’s teachings can be organized into three main areas: epistemology, metaphysics, and axiology. When you understand his beginning premises, it’s easy to see how his conclusions follow. |

Korihor’s philosophy does have a certain coherency; it’s easy to see how compelling it can be. One author antagonistic to the Church cynically concludes, “Since Alma can’t refute Korihor’s arguments, he says he’ll have God smite him so that he can no longer speak.”1 In reality, Alma does refute them, not only effectively, but also concisely.

What Alma Didn’t Do

While teaching among the Nephites, Korihor lays out a variety of complaints he has about the doctrines taught in the Church of Christ. He asserts that prophecies are just foolish traditions, that there is no life after death, and that guilt is caused by a frenzied mind rather than a conscience.

Alma could have taken the same shotgun approach that Korihor used, peppering Korihor with detailed counter-arguments to each of his assertions. The first time I read Alma 30, that is what I was expecting, or at least hoping for. I thought, “Alma might explain some ancient prophecies that had come true as evidence of their divine origin,” or, “He could explain near-death-experiences as evidence of life after death,” or, “Maybe he’ll talk about ‘Natural Law’ or what C. S. Lewis calls ‘the Tao’ as evidence that everyone naturally discerns basic good and evil without it necessarily being inculcated socially.”

In fact, Alma could have even brought up his encounter with an angel. He could have said, “Korihor, I have seen a divine being, so I do know they exist.” But Alma did none of this.

A Loose Thread

Instead, Alma seems to have recognized the fact that all the threads of Korihor’s philosophy rested on one premise: the idea that “ye cannot know of things which ye do not see.” Today we might call it empiricism, sensory empiricism, or observation—the notion that all knowledge can only be rooted in the five senses. As you can see on the chart from part one, all of Korihor’s conclusions grow out of this original assumption:

If that assumption can be called into question, the rest of Korihor’s assertions are likewise questionable.2 There is no need to address them item by item (although it isn’t necessarily bad to do so). In fact, to address them in the manner I mentioned at the beginning of this article would be to accept Korihor’s premise and thus let him pick the terrain. For example, if Alma had referred to his experience seeing an angel, that would imply that no one else should believe unless and until they also saw an angel with their own two eyes. The Church would be pretty small if that were the case. So for these reasons, and perhaps in the interest of expediency,3 given the fact that they had a public audience whose time was limited, Alma spends much of his time addressing Korihor’s base assumption.

Korihor said you can only know things you see. If he truly believed his original premise and followed it through to its conclusion, he would stick to statements like these:

- How do ye know of their surety [prophecies]? … Ye cannot know that there shall be a Christ.

- Ye do not know that [those ancient prophecies] are true.

- Ye do not know that there shall be a Christ. (v. 15, 24, 26)

However, perhaps as Korihor gained a following and became bolder, he stopped asserting doubt and started asserting knowledge. His statements of “You don’t know x” turned into “I do know y” :

- There shall be no Christ.

- God … never has been seen or known, … nor ever will be.

- There is no God. (v. 12, 22, 28, 45)

If his beliefs were truly based solely on sensory empiricism, he would not assert knowledge about the future or that God does not exist; rather, he would only assert, for example, that he himself does not know whether God exists. To make a positive statement that God does not exist goes beyond the scope of his epistemological premise and claims knowledge ungrounded in sensory observation.

Tugging at a String

Alma calls attention to this fact by “calling Korihor on the carpet,” so to speak:

I say unto you, I know there is a God, and also that Christ shall come. And now what evidence have ye that there is no God, or that Christ cometh not? I say unto you that ye have none, save it be your word only. (v. 39–40)

Alma insists that if Korihor is to be consistent, he must at most be an agnostic. This response used to leave me dissatisfied when I first read this account, because it seemed weak to me. I thought, “So the best thing we can say is, you can’t prove there’s no God? How is that going to convince anyone to believe in God?”

I later realized, though, that Alma’s position only seems weak if you assume Korihor’s epistemology. With Korihor’s assumptions about knowledge, the best you can hope for is a hung jury, a “We can’t say for sure.” But Alma never claims that sensory observation is the only way to gain knowledge. He only discusses evidence long enough to point out Korihor’s inconsistency and the limited claims he is able to make based on observation as the only source of knowledge. But Alma asserts another source of knowledge. In fact, he alludes to it in his critique of Korihor’s claims.

Alma at the Loom

Alma says that Korihor has no evidence for his beliefs “save it be your word only” (v. 40). That is, Korihor expected others to believe him that Christ would not come based on his witness, his personal testimony—like in a court of law. Alma believes that witnesses are a further source of knowledge beyond personal observation:

But, behold, I have all things as a testimony that these things are true; and ye also have all things as a testimony unto you that they are true; and will ye deny them? … Thou hast had signs enough. … Ye have the testimony of all these thy brethren, and also all the holy prophets. The scriptures are laid before thee, yea, and all things denote there is a God; yea, even the earth, and all things that are upon the face of it, yea, and its motion, yea, and also all the planets which move in their regular form do witness that there is a Supreme Creator. (v. 41–44)

Given this additional source of knowledge, we can do better than declare a null verdict. We can hope for more than just agnosticism because we have more to draw on than personal observation; we have witnesses and testimonies. Besides the evidences and testimonies in creation and in the scriptures, Alma explains elsewhere in his writings that the ultimate witness is from the Holy Ghost. That witness can, in process of time, grow into a perfect knowledge in the same way that a seed eventually becomes a tree. On that premise rests his own faith and knowledge.

Conclusion

Of course, Korihor does not publicly accept Alma’s premise that knowledge can be gained by means other than observation. And so he back-pedals a bit and takes back his claim to know that there is no God, revising it to be merely a belief. He also asserts limits on Alma’s knowledge:

I do not deny the existence of a God, but I do not believe that there is a God; and I say also, that ye do not know that there is a God; and except ye show me a sign, I will not believe. (v. 48)

This is an acceptable impasse. Many religious conversations can end here. We come to an understanding about each other’s epistemology, we shake hands, and we part ways. This is precisely what Boyd K. Packer did in a conversation with an atheist on an airplane. When Elder Packer testified that he knew there is a God, the atheist “protested, ‘You don’t know. Nobody knows that! You can’t know it!'” Just like Korihor, the atheist assumed that his own empirical epistemology was the only valid one, and that no one’s knowledge could go beyond the bounds of sensory observation. Elder Packer replied by explaining that his own epistemology included other means of knowing, including a witness from the Spirit. He “bore testimony to him once again and said, ‘I know there is a God. … And just because you don’t know, don’t try to tell me that I don’t know, for I do!”4 At that point, once the other person understands our epistemology of revelation, there is nothing left to do but hope they try it out. As Latter-day Saints, we are naturally saddened when people refuse to consider the possibility that knowledge can come through a witness of the Spirit, such as when they decline Moroni’s invitation to pray about the Book of Mormon. But there is always hope on the horizon that at some future time they will change their minds and “try the virtue of the word” (Alma 31:5).

However, Korihor’s story did not end this way. The Lord intervened in a miraculous way, punishing Korihor for his actions. Why was that necessary, if Alma had already succeeded in thoroughly answering Korihor’s arguments and explaining the Saints’ basis of knowledge? I wondered this as a youth—did Heavenly Father expect me to circle wagons or take the offensive every time someone disagreed with the restored gospel? If it was not enough for Alma to just shake hands and part ways, does that mean it is not enough for us today to just agree to disagree?

I believe it’s almost always fine to engage in friendly dialogue and to live and let live. I will try to show how Korihor’s situation was an exception to that norm in my next post.

Notes

All scripture citations are from Alma chapter 30 unless otherwise indicated. Image credit: Alma Arise, by Walter Rane.

1. Steve Wells, “The Wisdom of Korihor,†http://dwindlinginunbelief.blogspot.com/2006/08/wisdom-of-korihor.html.

2. One commenter on the previous article hit the nail on the head when he said, “Strike at the root Alma! Don’t get distracted by the details.”

3. It’s also possible that Alma’s response was more plenary and thorough, but since Mormon was editing the account, he constructed the narrative to cover only the most salient points.

4. Boyd K. Packer, “The Candle of the Lord,†Ensign, Jan. 1983, p. 51.

Thanks, a profound analysis!

Thank you for this series.

I like how you’ve pointed out that all Korihor’s arguments are ultimately built on one cornerstone belief—That things that are unseen cannot be known. (Sometimes I wonder if we can even rely on the things we think we’ve seen.)

In the past, I’ve thought that Alma should have addressed more specific points too. I think we feel obliged to answer all concerns, even though they are often a smoke screen, or only put up to distract or overwhelm. I think Alma’s approach is better: Address the root of the problem (not the symptoms), and then move on with your own points/testimony so the truth can be heard.

Alma did not spend all his time playing defense (which many of us do). After quickly and precisely addressing the concern, he went on offense and taught some basic things to Korihor and those listening to the debate.

That’s a good point—Alma cleared the table and then asked some questions of his own. That doesn’t mean we need to be antagonistic to every question-asker, but Korihor had proven himself combative, which is probably why Alma was more active in addressing Korihor’s beliefs, rather than just answering questions about his own. I plan on talking about that in my next post. I think in another situation, it would have been fine to address Korihor’s specific points (like Elder Ballard did in this story). There were reasons Alma didn’t.

Rats, I couldn’t find the link to Elder Ballard’s story. It’s about a young LDS guy, returned missionary, I think. He starts to lose his testimony and he gives Elder Ballard his list of questions. Elder Ballard says they’ll meet in a week to talk about it, but on the condition that the young man read the Book of Mormon every day that week. When they meet a week later, the guy says, “Nevermind. I’ve got my testimony back.” Elder Ballard says, “Good. Now sit down. We’re going to talk about each of these questions.”

Anyone know the reference for that story?

Excellent perspective on this story. I appreciated it. One thing that stuck out to me recently when reading this story was that Alma told Korihor that he was possessed of a lying spirit that caused him to continue to resist the Spirit of the Lord. This is a particularly disturbing assessment of Korihor, because it meant that no matter what he was told, inside, his mind was inclined to disbelieve it and resist it and he wanted to say something opposite. Spiritually that’s pretty far gone. Alma, having once upon a time been in a similar situation of trying to destroy the church with vain and flattering words knows the depths to which Korihor has sunk. A divinely administered “shock” had helped Alma, perhaps one would help Korihor. Unfortunately, once Korihor was struck dumb, rather than go through a period of torment and suffering, he immediately tries to get the curse removed by someone else’s prayer, without effort on his own part. Perhaps that was how Alma knew that Korihor had not really changed, even though he was recanting on paper.

That’s interesting. It seems obvious now, but I’d never thought to contrast Alma’s shock with Korihor’s muteness. Maybe one difference is that Korihor asked for the miraculous intervention to be over, rather than submit to it for as long as the Lord willed. Maybe the fact that he asked was one indicator that he still hadn’t learned from it. Interesting.